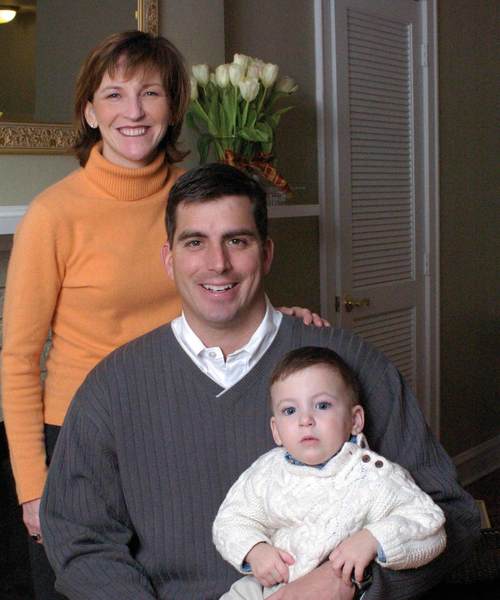

Adam Sargent

Former Irish lacrosse standout still contributing to Notre Dame programs

When Adam Sargent arrived at the University of Notre Dame in the fall of 1993 from Brighton High School in Rochester, N.Y., he envisioned not only working with his teammates to achieve success on the lacrosse field but also looking forward to the day when he received his diploma in the shadows of the Golden Dome.

He could not have foreseen how this education would prepare him for the challenges ahead.

Sargent’s life was changed forever 13 years ago. At 8:30 on the morning of May 29, 1997, the 21-year-old senior, who had distinguished himself on a team that qualified for three straight appearances in the NCAA lacrosse tournament, was on his way to nearby Saint Mary’s College to take an exam when he was involved in a two-car accident at the intersection of Notre Dame Avenue and Angela Boulevard. The accident separated Sargent’s neck at the C-7 vertebrae and left him paralyzed from the chest down with somewhat limited use of his arms.

Sargent’s focus soon changed from winning games to learning how to live again. He not only graduated from Notre Dame with a double major in history and anthropology in 1999, but also matriculated to become a valued member of the University’s Academic Services for Student-Athletes, counseling members of the football, ice hockey and women’s golf teams.

“I have developed a unique relationship with Adam over the years and he has often heard me say, ‘The Lord works in funny ways,’” Pat Holmes, Notre Dame’s director of academic services, said.

“I have never said this in describing Adam’s situation, but in reality, Adam would not have chosen this path had he not been hurt. Having worked with him and watched him interact with others, I can honestly say that there is not a day that goes by that Adam does not impact someone’s life in a positive way.”

All too often, teachers say, “Do what I say, not as I do.” What could have been a tragic tale about a fall from greatness has turned into a lesson in how to give back to those who helped him at a time when he needed them most.

Sargent’s disciplined sensibility to understand what others may perceive an injustice that could have burdened his life has given him an ability to help others on the Notre Dame campus.

“I think I’ve always been a pretty empathetic person,” he said. “I was raised that way. My parents stressed an appreciation of what we have, not only in our family, but also in the American culture. Obviously, there is a lot of poverty and difficulties, but we were in the upper middle class and they were always good about making sure I had a social conscience with what was going on not only in our country, but around the world.

“I say this because a large part of my ability to cope with this devastating injury is I didn’t spend a lot of time asking why it happened. I didn’t spend a lot of time having to absorb the shock, the realization that I was mortal, the realization that bad things happen.

“I think a lot of people are insulated in this country and it’s a beautiful thing to live in a relatively safe culture. So when it happened, it was a completely devastating thing and I was grief stricken with my loss at that age, being a student-athlete and having not only so many of the activities that I valued taken from me, but also in some way having to reshape my identity as to who I am and how I define myself.

“That part was hard. When you hear stories of civil war in Rwanda and genocide in Chechnya, all these things are very real and happen to people like me all over the world. But I don’t think people here take it to heart because it’s happening to someone else. Then when it happens to them, it’s, ‘How could this happen to me?’ I was in a car accident and that was unfortunate. But that’s all it was. A car accident.

“Now, the result was very difficult for me. But I think I had an appreciation for the fact that we’re not guaranteed anything in this life and when these things happen—even when they’re dramatic—you have the ability—if you choose and if you’re graced with the support network I had, not only my family, but the Notre Dame family, the athletics family—to respond in two ways. You can either have a pity party and find the reasons you won’t be successful or you can grieve, mourn and work toward healing.

“I firmly believe it is each individual’s responsibility to do their part to make as much meaning of their life as possible. With the support and the great people around me, I was afraid of failure. And that was a hell of a motivating factor. I wanted to be independent again, wanted to pursue something that not only gave meaning to my life but also gave meaning to others.”

Sargent once was a healthy, vibrant young man who loved the outdoors and sports such as skiing. But he was forced to start his life over when he was confined to a wheelchair. His lacrosse coach, Kevin Corrigan, was the first one there at the hospital.

“I was the only one there with him,” Corrigan said. “It was just horrific, looking at this vivacious young man, laying there on the table unable to move, scared to death and feeling completely ill-equipped to know what to do or how to handle the situation.’’

After Sargent was initially stabilized, he was transferred from South Bend to the rehabilitation center at Northwestern University, where he learned how to function on a daily basis.

In the fall of 1997, following three months of rehabilitation, Sargent returned to Rochester but lived independently in an apartment near his family’s home. Adam’s mother spent nights with him, but during the day, he began learning the process of living on his own.

With the encouragement of the Rev. Al D’Alonzo, C.S.C. (he served as a counselor and worked as the men’s lacrosse team advisor in the academic services department), Sargent returned to campus to complete his studies. He lived in nearby Mishawaka in a customized apartment that was adapted to meet his needs. He commuted to classes in a wheelchair accessible minivan purchased with money raised by a fund started by Corrigan (to date it has raised more than $210,000).

Corrigan has been instrumental in ensuring that Sargent and his family could handle his difficult situation as best as possible. He met Sargent’s parents, Walter and Roberta, at the South Bend airport when they flew into South Bend that night. He later accompanied them to a dorm fund-raiser that raised $5,000 and helped, along with his players, set up a “Meet the Irish” function in which fans could interact with every athlete on campus for the price of $5.

“That’s what a community is all about,” Corrigan said. “Helping each other. There was no hesitation from anyone within the Notre Dame community and the lacrosse program to do what we could. We just tried to take the outpouring of love and concern that was coming in for Adam. People just kept saying ‘What can I do? What can I do?’ So we decided to start a fund because, no matter what the result of this was, there were going to be extraordinary expenses involved with his recovery.

“It was traumatic watching him go through that, but it was also one of the most triumphant things I’ve ever been around. There were some painful moments for him, but I’ve been continually and constantly amazed at him and his ability to move on and maintain the same kind of vitality he always had and the same enthusiasm he always had.

“I talked to a recruit we signed recently and I asked him, ‘Why Notre Dame over other great schools?’

“And he said, ‘Notre Dame has a soul.’

“Notre Dame is people like Adam Sargent.”

After graduating from Notre Dame, Sargent was offered a chance to attend the University of Virginia and work on a master’s degree in counseling, but chose to stay close to the people who were there for him, accepting an internship in academic services that morphed into a full-time job offer 10 years ago.

“I think if I was not independent, it would be a very different situation,” he said. “That element is something that allows me to deal with all the other frustrations in a very constructive way. Part of it’s luck. I have an injury between the fifth and sixth vertebrae that’s pretty high up. I think technically, that’s quadriplegic, not paraplegic. A couple centimeters north and I probably would not be independent.

“At this point, I have the mobility in my biceps, triceps and shoulders. I can transport myself and I can get dressed. I can drive and do all this stuff. I’ve worked hard to make sure I maintain strength and maintain my body, but I just have to say I’m lucky the injury wasn’t a centimeter or two higher. I’ve worked hard in the rehab center to understand how to take care of my body, how to transfer, how to get the most strength and condition out of what I have.”

On a personal note, he also found someone to share his life. He and Chenn, a graphic designer and artist from Purdue, were married in 2008. She is currently working for the local YMCA, teaching art to children from a charter school in South Bend and doubling as a nanny to twins born to assistant basketball coach Martin Ingelsby and his wife Colleen (she works with Sargent in academic services).

“I think we do a great job at this University,” Sargent said. “We have an athletics program that is admired for respecting the importance of young people in both education and degree. If we’re not doing that—the people who work with college athletes—it’s nothing short of exploitation.

“We provide them with opportunity for a free education for those on scholarship. But that really can’t be quantified in terms of empowering them to make a living for the rest of their life, empowering them to have a rich experience educationally that helps them grow as a person, but also come back to their communities and make a great, great impact.”