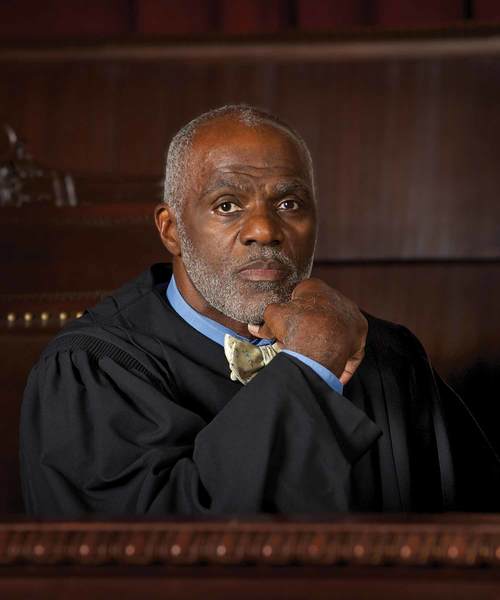

Alan Page

He dedicated his life to education

Alan Page will go down as one of the most talented linemen ever to play the game of football, but he wants to be remembered for something else—bringing hope to young people of color.

Page arrived at the University of Notre Dame in 1963 on an athletic scholarship from Central Catholic High School in Canton, Ohio. He found an all-male and virtually all-white campus. There were only a handful of teammates who were black, and no coaches of his color. It was his first time away from home, adding to the challenges of adjustment. To some he came across as aloof, which was in reality a result of being shy and lonely. He looks back on his Notre Dame degree in political science with a certain wistfulness, like someone who dated a lovely woman but failed to deepen the relationship.

“Notre Dame gave me a solid academic foundation, but I was too distracted at the time to discover a love of learning for its own sake, which would only come later,” says Page, who eventually would hold two honorary degrees from his baccalaureate alma mater.

The “distraction” was football, at which Page excelled.

He was disciplined, hardworking and focused. Playing defensive end at 6-foot-4, 238 pounds, he was preternaturally quick with great instincts about where the play was going.

“Trying to block Page was like trying to block a ball bearing,” is the way one observer put it.

He led Notre Dame to a national championship in 1966 and an overall mark of 25-3-2 from 1964 to 1966. Drafted in the first round by the Minnesota Vikings, he had 173 sacks, 28 blocked kicks and 24 recovered fumbles in his 15-year, 218-game National Football League career with the Vikings and Chicago Bears. Veteran football writers still talk of a Vikings–Detroit game in which Page, now a defensive tackle, was penalized for off-sides on consecutive plays. After protesting vigorously but unsuccessfully, an angry Page singlehandedly stopped two running plays for losses, sacked the quarterback then blocked a punt. A film review later showed Page was not off-sides on either play for which he was flagged.

Page is in both the college and professional football halls of fame. It was at his 1988 induction to the NFL Hall of Fame in his hometown that the honoree—not for the first time— showed he sometimes thought otherwise. He asked the black female principal of a Minneapolis high school to introduce him, eschewing the usual selection of a coach or teammate. Then he used his own podium time not to wax nostalgic about playing field glory but to launch the Page Education Foundation to encourage students of color to pursue post-secondary education.

“I don’t know when children stop dreaming,” he told his audience, “but I do know hope starts leaking away because I have seen it happen.”

He vowed “to go back into the schools and find the shy ones and the stragglers, the square pegs and the hard cases” before they had given up on the system or the system had given up on them.

Standing on the very spot where his summer job as a teenager was sweeping cement floors during construction of the Hall of Fame building, Page was echoing a commitment his parents made to his own education. His mother was an attendant in a country club locker room; his father ran a saloon with gambling in the back room. Both talked constantly to their children about education as the key to a better life.

“My father’s skill with numbers when it came to gambling was phenomenal,” Page recalled. “I have often wondered where he could have ended up had he applied it elsewhere.”

Launched that hot afternoon at a football celebration in a hardscrabble industrial town, the Page Education Foundation has over time supported 4,800 Page Scholars, students of color studying at universities, colleges and technical schools in Minnesota, as well as at Notre Dame. (The role of the Minnesota Club of Notre Dame in raising funds for the foundation accounts for the fact that it is the only school outside the state to which Page Scholars can apply.

As a Supreme Court justice, Page himself cannot solicit money for the foundation he started.)

Formally committed to giving back to their communities, Page Scholars have provided 300,000 hours of mentoring and tutoring younger children of color. The Page Education Foundation targets a major state problem. Minnesota’s economy creates one of the country’s greatest demands for a highly educated workforce while its high school graduation gap between white students and those of color is among the nation’s worst.

Page remains convinced that the building blocks for educational achievement are reading and writing. When mastered early on, they open up opportunity. When neglected, they foreclose options, especially for young people of color. That is why his foundation once joined Kodak in sponsoring an essay contest for 4-year-olds and why you will find the associate justice himself reading to at-risk kids in Benjamin E. Mays International Magnet School’s Power Lunch program in St. Paul.

“I’m inspired by young people,” Page once said. “That is where the hope is.”

His own journey from football stadium to appellate courtroom is one Page believes started early. Even the young growing up in Canton could see that lawyers had bigger houses than steel mill workers, and on television Perry Mason never lost a case. But one legal decision by the Supreme Court of the United States was recognized as significant by a 9-year-old black youngster.

“Brown v. Board of Education seemed somehow important to what the law was really about,” says Page, “and also affected who I am.”

Much later in life, he combined playing professional football with study in the University of Minnesota Law School, even convincing unbending Vikings coach Bud Grant to give him a pass on one training camp. Page also gained some practical experience in conflict resolution as the National Football League Players Association representative for the Vikings. He sometimes got ahead of his blockers, so to speak, and on one occasion went out on strike against management—alone.

Following his law degree in 1978 and during a time when many NFLers worked in the off-season, Page practiced employment law in a large Minneapolis firm and eventually joined the staff of the Minnesota attorney general. In 1992 he was elected to the nine-person Minnesota Supreme Court as the first African American to hold a major state office. He was the biggest vote-getter in state history when re-elected in 1998 and became the court’s senior justice after reelections in 2004 and 2010. What strikes one about his resumé is that his honors and awards, which are many and varied, more often reflect Page’s contributions to society than his exploits on the gridiron.

The Minnesota Supreme Court oversees the state’s system of justice, an area of particular concern to Justice Page. Shortly after he was sworn in, a task force examining racial bias in Minnesota criminal justice found that, “everything else being equal, people of color are arrested more often, charged more often, given higher bails, tougher pleas bargains, less fair trials, and far longer sentences,” Justice Page told a Notre Dame Commencement audience in 2004. Similar findings, he said, have been made by the 30 or more states that have conducted such studies. “There is something fundamentally wrong,” Justice Page pointed out, “when the one branch of government designed to protect individual rights denies equal justice to communities of color.”

Page’s legal philosophy was simply put on one of his campaign posters: “Justice for All.” Seated in chambers in Minnesota’s Judicial Center in the shadow of the State Capitol, he puts his extraordinarily long fingers together in front of his closely trimmed, grey-white beard and customary bow tie. He describes, reflectively and deliberately, how he attempts “to ensure that everyone who stands before me has his or her claims addressed in as impartial a manner as possible.”

He later talks about his favorite item among segregation-era memorabilia collected by him and his wife, Diane. It is a handmade, canvas sign waved at a presidential casket as it made its way in a funeral procession through New Hampshire in 1865.

One side reads: “Uncle Abe, we will not forget you!” The other: “Our country shall be one country.”

“We’re still working at it,” says Justice Page.