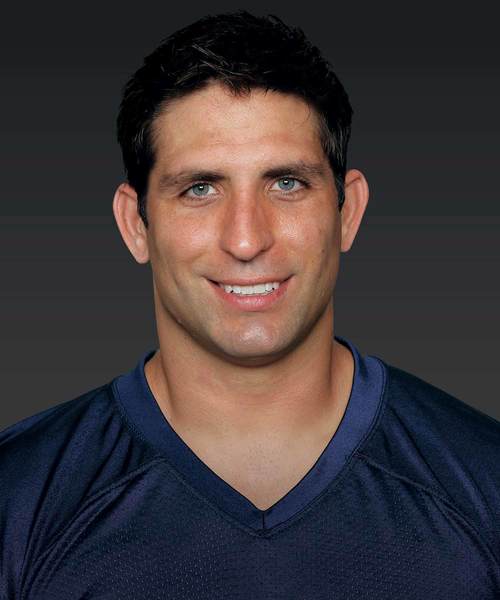

Anthony Fasano

Writing the ‘next chapter’

Anthony Fasano, a 2006 University of Notre Dame graduate, is a giant of a guy with a big heart.

Think Andre the Giant’s kind, gentle Fezzik in “The Princess Bride,” but somewhat smaller.

An 11-year National Football League veteran, Fasano is a 6-foot-4, 255-pound Tennessee Titans tight end. He has the soft hands fashioned for catching fastball spirals, and he has a lumberjack’s strength suitable for protecting quarterbacks and busting open holes for ball carriers.

There’s more to Fasano, though, than just pass routes and pocket protection.

As a husband, a father, an entrepreneur and a good Samaritan in multiple measures as founder/owner of Florida-based Next Chapter Addiction Treatment and founder of the New Jersey-based Anthony Fasano Foundation, he’s equally savvy at managing competing responsibilities. It’s a knack for multitasking he jokingly refers to as “spinning plates.”

Before we get into Fasano’s carnival act, however, there’s a story to tell, one about putting the needs of other people ahead of his own. It’s about a male relative of his, an athletic guy in his own right who played high school football against Anthony and later played ball at a Division III school in their shared home state of New Jersey.

After graduating from college, Fasano’s brotherly pal became a high school gym teacher and basketball coach, an all-around good guy even a prominent pro athlete could admire.

Then came the phone call.

Ron (not his real name) had gone missing.

“We thought he might be dead,” Fasano says. “A good friend of mine who’s a police chief up in New Jersey gave me a call and says, ‘Hey, I got a report across my desk that mentions (Ron’s) name

and a drug ring they are about to bust.’

I couldn’t believe it.”

At the time, it was January, often a bitterly cold time in the Northeast. A manhunt was underway, although eventually Ron returned home after being missing for seven days, at times nearly freezing. “I need help,” he told loved ones.

A heroin addict who had also gotten hooked on pills and alcohol, Ron got that help. Fasano’s mother, a nurse, called a friend to get Ron into a detox center, where he stayed for a week of bodily toxins-expelling misery before going to Florida for an extended stay at a treatment center.

Drugs and alcohol had changed Ron for the worse. His plight made Fasano a changed man as well, but in a different way.

“This opened my eyes and has helped me learn not to put people into boxes, not to assume they have brought this upon themselves,” says Fasano, who admits he had long regarded addiction as an excuse or weakness. “I have an eight-month-old daughter, and when you have your own kids and see stuff like this, you start looking at things a lot differently, like bullying in schools.

“In many cases an addiction is the result of trauma in a child’s life. It could be an abusive parent, a neglectful parent. What I’ve learned is that when trauma happens in a child’s life, they stop progressing. Later in life when they encounter an adverse situation, they go back to being that 13-year-old. They never really grow and mature past that time.”

Once Ron completed his treatment stay in Florida, he tried going back to New Jersey to resume his life there, but he didn’t stay long.

“He realized it wasn’t for him,” Fasano says.

So Ron returned to Florida and took a job as a resident tech at the same facility where he had been treated.

With Fasano back home in Florida for the offseason, Ron occasionally drove to Fort Lauderdale so they could meet over lunch or dinner. A common topic of conversation was what Ron described as corners-cutting corruption in the addiction-treatment industry (“the wild west of health care” Fasano calls it), but he also shared some sound ideas about how it could be better. Fasano was intrigued, and he acted.

Through some contacts Ron had made in Florida, Fasano was able to cobble together a small circle of addiction-treatment experts who shared his and Ron’s vision for what would become Next Chapter.

It started out housed in a residential home in Delray Beach, Florida, that Fasano, also a real-estate buff, bought and eventually opened for patients in December 2015. As of fall 2016, Fasano and his team had purchased and were in the process of opening a second house on the same street, giving them 19 beds total.

On its website (nextchapteraddiction.com), Next Chapter is described as “an all-male residential facility, focused on the treatment of drug and alcohol addiction, resolving past trauma, and overcoming other addictive/compulsive behaviors … Much of the work we do at Next Chapter involves working through traumatic and shame-inducing events from childhood, which have greatly impacted our patients in a host of detrimental ways.”

In opening the facility, Fasano and his Next Chapter startup team committed to a treatment center that would blend a strong clinical program with the best therapeutic modalities and a 12-step philosophy—“the best of both worlds,” as CEO/clinical director Abe Antine describes it.

“It’s obvious that Anthony is really pumped to be involved in something like this,” Antine says. “During the offseason he’s here in the office several days a week. Even during the season we are in contact almost every day, bouncing ideas off of each other, and he’s making marketing calls. And whenever we get new employees, regardless their position, Anthony has conversations with them.

“He’s very involved. I think once his football career ends, this will become an even bigger thing for him.”

Fasano played in his second season with the Tennessee Titans in 2016. Drafted in the second round of the 2006 NFL Draft by the Dallas Cowboys, Fasano spent two seasons with the Cowboys, playing alongside future Hall of Fame tight end Jason Witten before being traded to the Miami Dolphins, where he spent five years and started 76 of 80 games, averaging 35.4 catches a season for the Dolphins. A free agent, he then signed in 2013 with the Kansas City Chiefs and played two seasons there before joining the Titans in 2015.

As a recruit coming out of Verona High School in Verona, New Jersey, and later as a player for the Fighting Irish (2002-2005), Fasano experienced the distinction of going through four Irish head coaches in a little over four years: He was originally recruited by and made an early commitment to Bob Davie, before Davie was fired and replaced by George O’Leary, whose falsified resume led to his resignation after five days on the job. Tyrone Willingham replaced O’Leary and coached Notre Dame for three seasons before he was let go and replaced by Charlie Weis beginning in 2005, Fasano’s senior season.

“(O’Leary) was on his way to see a high school basketball game of mine, and I was getting warmed up when my coach told me that he wasn’t coming, that they had turned the plane around,” Fasano says. “But I didn’t commit to a coach, I committed to a school. I hung on and was happy to play for coach Willingham and then coach Weis for my senior season.”

Fasano finished his Notre Dame career as the school’s second-leading pass receiver among tight ends with 92 catches for 1,112 yards (12.9 yards per catch) and eight touchdowns. In 2005 he also received the Nick Pietrosante Award, given annually to the Notre Dame football player who best exemplifies the qualities of courage, loyalty, teamwork, dedication and pride.

It was in his second season in the NFL that Fasano took his first step into full-time philanthropy and humanitarianism, launching his foundation in New Jersey. His original intent was to help autistic children in underprivileged families.

“I started out wanting to give back to my home area in New Jersey, and it seems the number of children with autism in that part of the country is greater than it is in other parts,” Fasano says. “There weren’t enough resources for them, and studies have shown that the most successful strategy is early intervention.”

Eventually Fasano and his foundation staff branched out to military veterans and their families and then undernourished families in the area, starting with a food drive.

“I don’t know the number, but we had lines around the block, and the appreciation these people showed was just unbelievable,” Fasano says.

Perhaps Fasano’s deep empathy for autistic children, for veterans, for the undernourished and for anyone suffering with addictions—Next Chapter accommodates a wide range of addictions to include drugs, alcohol, internet, sex and gambling—emanates from his broken-family background.

His parents divorced when he was 12, leaving him, his two sisters and his one brother—eight and a half years separating oldest from youngest—leaning as much on one another as they did on their separated mom and dad.

“I love being close to my siblings; we did everything together,” Fasano says. “Despite the typical issues with a divorce, I had a pretty good childhood.”

“The thing about Anthony is that he’s such a humble guy,” Antine says. “He wants to be a part of the team, and there’s no pretentiousness about him. He’s all in.”

Although it wasn’t his original intent, Antine, about six months after Next Chapter’s launch, invested some of his own money alongside Fasano’s so he could have an equity share in the center.

“I know I’m dealing with a genuine, trusting person, someone I feel totally safe with,” Antine says of Fasano. “I’ve been frustrated with the direction this industry has taken with all the greed, corruption and mediocre facilities—not that they are necessarily doing harm, but they just aren’t being very efficient. We want to change that.”