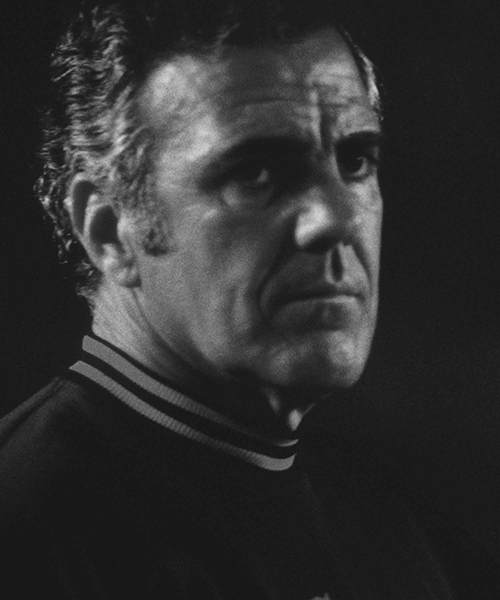

Ara Parseghian

The shining light of Irish Camelot: Flickered out

Camelot ended in early August at the University of Notre Dame.

That’s a reference to the sort of idyllic football paradise and atmosphere that College Football Hall of Fame coach Ara Parseghian created in his 11 seasons (1964-74) that produced 95 victories and a pair of mythical national championships for the Irish.

His death on Aug. 2, 2017—coming at age 94—ended a more than 50-year association with the University, beginning with the 1964 football season.

His charismatic and passionate intensity didn’t fall by the wayside after he retired from coaching. Parseghian launched himself into the fight against multiple sclerosis—a disease that had afflicted several in his family, including his late daughter Karan—and then later devoted extensive time and resources to create, promote and fundraise for the Ara Parseghian Medical Fund, now housed at Notre Dame. That effort battled Niemann-Pick Type C, an incurable disease that claimed the lives of three of his grandchildren.

Parseghian ran the Irish program with a stern hand, yet his charges—players, assistant coaches and administrators—lovingly and reverentially held him in the highest regard. In maybe the ultimate compliment, the 1966 Notre Dame Football Guide in Parseghian’s biography suggested, “He invented desire.”

Former Irish quarterback Terry Hanratty recalls how Parseghian reacted after the signal-caller’s noteworthy sophomore season debut against Purdue in 1966 (16 completions on 24 attempts for 304 yards in a 26-14 Notre Dame victory over the eighth-ranked Boilermakers). Hanratty oozed confidence; Ara responded with corrective critiques.

Said Hanratty in 1980 to Skip Myslenski of the Chicago Tribune, “He knew I could become obnoxious and hurt the team, so he burst my balloon. He wasn’t going to let me get a big head. I walked out of there thinking, ‘Geez, I got a lot of work to do tomorrow.’ It was like going back to square one. He was a genius.”

Much of that reverential approach came through the way Parseghian turned around the Irish program when he was hired away from Northwestern—probably not coincidentally after his Wildcat teams defeated Notre Dame four straight times. In a historic series that dates to 1889 and spans 48 games, that quartet of victories (1959-62) marked the lone Wildcat triumphs between 1940 and 1995.

The on-the-field productivity of Knute Rockne and Frank Leahy (still the all-time two winningest coaches in NCAA history by percentage) certainly suggested that Notre Dame football had seen its share of glory years. Yet, when Parseghian came to campus, the Irish had endured two-win seasons three times in the previous eight years. Those same eight seasons produced a combined 45 defeats, the worst stretch in Notre Dame history in terms of cumulative losses.

The Akron, Ohio, product and Miami (Ohio) University graduate took over a 2-7 Irish squad when he was named to the job in December 1963. He promptly created the biggest season-to-season turnaround in Notre Dame history, the greatest by any team in the 1964 season and the seventh largest (six and a half games) in major college annals, at that time, The Irish spent the month of November ranked number one in the polls and finished 9-1.

That 1964 team came ever so close to winning the national title—falling 20-17 on the road to USC in the season finale on a Trojan touchdown pass in the final two minutes. Despite that blemish, Notre Dame received the MacArthur Bowl from the National Football Foundation. Parseghian’s record from there—including the 1966 and 1973 national titles—speaks for itself. The Irish never once lost consecutive regular-season games in his 11 seasons.

The 1964 turnaround created such an impact that 45 years later noted sports author Jim Dent wrote a book—titled “Resurrection”—about that Notre Dame football season.

Parseghian’s stay in South Bend featured some other noteworthy circumstances:

—The success of his teams led the University to reverse its position on playing in postseason bowl games, with Ara leading the argument that Notre Dame needed to participate in those contests to be considered for national championships.

—Home game Friday night pep rallies at the Old Fieldhouse, with Parseghian and his team in the balcony, were legendary affairs in those years. And with women not arriving at Notre Dame until the last few years of Ara’s tenure, assuredly campus life took on a different dynamic in those early seasons.

—While linear radio remains a college football staple, the Mutual Radio Network flourished during Parseghian’s time, with nearly 400 stations carrying Irish games. On the television side—and with the NCAA limiting live games to a few per team per season—Notre Dame benefitted greatly from its Sunday morning replays produced by the C.D. Chesley Company. Those two networks made household names of announcers Van Patrick, Al Wester, Lindsey Nelson and Paul Hornung for Irish followers.

—The rekindling of excitement in South Bend meant that Notre Dame merited coverage from not only publications like Sports Illustrated, but also TIME and LIFE, including TIME cover appearances by Parseghian in 1964 and Hanratty and Jim Seymour in 1966.

Tom Pagna, Parseghian’s longtime offensive backfield coach and close confidante, had this to say in his 1976 book “Notre Dame’s Era of Ara”: “I suppose it could have happened at another school, a place where football tradition had once been grand and glorious and then diminished for one reason or another. But certainly regeneration of those programs would not command as much national attention at it did at Notre Dame. And I doubt it would have as much impact if it were to happen today at Notre Dame.”

Yet, with all the success, Parseghian’s intense approach took its toll. He made the decision to step away from coaching after 24 years as a head coach—and never returned to the field or looked back (other than to coach in the final College All-Star Game in Chicago in 1976).

Hanratty told Myslenski, “My freshman year there was his second year, and he was striking, a very good-looking guy. But about five years later I saw him at a banquet in New York and thought, ‘My God, what have you been doing to yourself?’ His hair was grayer. He looked tired. He did not have the bounce. He’d slowed down. It wasn’t Ara.”

Yet Parseghian only knew one way to go about his duties—with clip-on ties and loafers giving him precious more time to work.

“You have to operate in a manner based on your own personality, on your own makeup,” he told Myslenski. “I did not change over the years. I remained excitable. I always got emotionally involved.”

When he had had enough, he walked away.

Parseghian’s decision to continue calling South Bend home—he eventually moved from his West Washington Street home to Granger—meant he remained a fixture on the Notre Dame scene and a resource for the Irish football coaches who followed. Though Parseghian’s game day intensity prompted his preference to watch Irish games on television from home, he remained close friends with his successors—notably Lou Holtz and Brian Kelly with whom he participated in golf and other events that benefitted the foundations of that trio.

Early mornings in Ara’s coaching days generally found him at Milt’s Grill in downtown South Bend, sharing coffee and football talk with longtime South Bend Tribune sports editor Joe Doyle. And his later years saw him headline the ROMEO group (Retired Old Men Eating Out), a lunchtime conclave of his Notre Dame associates and local businessmen. He played golf regularly until his hip issues made that unrealistic some years back.

After he left the football sidelines, Parseghian translated his intense approach to the personal fight to find a cure for Niemann-Pick Type C.

Offered Notre Dame vice president and James E. Rohr athletics director Jack Swarbrick, “In the middle of my career an organization I helped run in Indianapolis was recognizing Coach Parseghian in his fight against this insidious disease. There were about 2,000 people at the event, and we presented him with an award and a donation. After he spoke I went up and introduced myself and I said, ‘Coach, I can’t tell you how moved I am by your commitment to this cause and all the energy and time you put into it.’ He said, ‘Jack, it would only be notable if I did not do it.’ That struck me as such a poignant expression of the things he valued over anything else.

“You saw a number of things this past season that we did in tribute to Ara—his name on the helmets and video tributes during the games. None of that will ever be enough. It can never begin to match the impact he made on family—his own, this University’s and the family of our football program.”

Miami University president Greg Crawford went to Oxford, Ohio, after serving as dean of the College of Science at Notre Dame during the time the University brought the Ara Parseghian Medical Research Foundation in-house. He made a massive personal commitment to the cause by making multiple cross-country bicycle rides to raise funds and awareness for the NPC fight.

“In the first few months before my inauguration at Miami, I sat down with my team and they said I had the opportunity to give the highest honor that’s given by Miami University,” says Crawford. “At Miami we use the phrase ‘love and honor’ to explain how our values merge. The President’s Medal was going to be given to someone who exemplified that in every form and I didn’t have to think about that for one second before I knew who that medal had to go to. If you know three things about Coach, it’s his courage, his grace and his humility.”

Adds former Notre Dame football student manager Jim McGraw, “Coach taught us the importance of discipline, the dedication to a goal, the value of unbreakable unity, always doing things with class, even when we lost. He taught us how to live and it stayed with us all our lives.

“The one thing I will always remember that he said—‘There is no circumstance that we cannot overcome.’”

Dan Novakov, former Irish offensive lineman, says, “He knew attacking Niemann Pick Type C would be a long hard journey. He never complained despite the intense pain he and his family have endured. In Ara’s memory we are committed to finding a cure for Niemann Pick Type C. All we need is more time and more money. We will find a way.”

Even with the landmark football bowl wins over the likes of unbeaten and top-ranked Texas and Alabama teams joined with the white-hot intensity of the rivalry with USC, it’s the players who could best define their coach.

Talk to 1964 captain Jim Carroll or his 1966 counterpart, Jim Lynch.

Listen to the memories of John Huarte (he won the Heisman Trophy in Ara’s first season in 1964), Hanratty, Joe Theismann or Tom Clements—just a few of the stars who played quarterback under Parseghian.

Recall the passionate manner in which former Irish lineman and athletics director Mike Wadsworth spoke of the turnaround in 1964.

Long after they had played for the Irish and graduated, they still had the sense that whatever relationship they had with their head coach, it amounted to something special and ongoing.

1960 marked the release of the movie Camelot (and the election of John F. Kennedy as president), hence the then-current pop culture reference.

The final curtain on the Era of Ara, in all its Camelot-like euphoria, has come down.