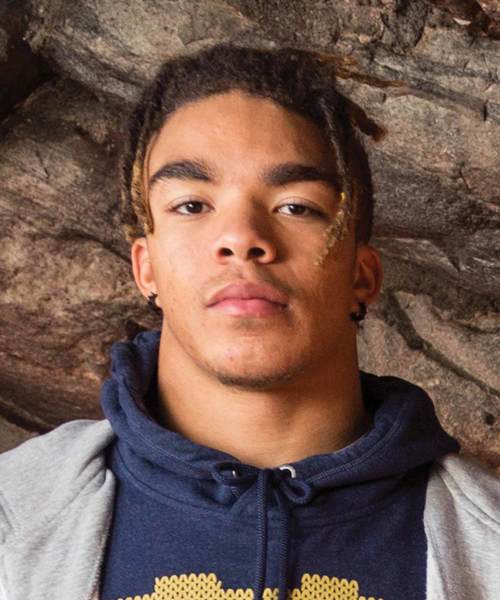

Chase Claypool

Until We Meet Again

Chase Claypool was just a precocious, outsized, bike-riding, basketball-loving teenager when his mother Jasmine woke him about 6:30 one morning a little more than six years ago.

Claypool barely heard what his mother said to him, was convinced he was dreaming and went right back to sleep.

When he finally awoke he found his mother crying in the kitchen.

“That’s when it started to click,” says Claypool, now a sophomore on the 2017 University of Notre Dame football squad.

The news she had delivered was that Chase’s older sister Ashley was gone. She had taken her own life—a fact neither Chase nor his mother could immediately comprehend.

“I never wanted to believe it,” he says. “I always thought it was some kind of mistake.

“It did not set in for me as a kid until the funeral when I broke down. I never saw people in my family—my stepbrother, my dad—cry like that.”

And so began the complicated process of dealing with a loss so personal that it could not be explained.

“Every time I saw her she was really excited to see me,” says Chase. “The last time I saw her she yelled my name down the street, she asked me how things were going. She was really proud of me. We were really close in the sense she was always happy for me and I loved her. I was doing a lot of sports then and she knew all about that.”

The youngest in a family of four brothers, two step-brothers and a sister, Claypool remembers when most if not all the kids in the family did karate and gymnastics when they were ages five and six.

Flash forward to his teenage years when Claypool was convinced serious BMX biking was maybe in his future.

Prentice Lenz, the basketball coach at Abbotsford Senior Secondary School in Abbotsford, British Columbia, recalls seeing Claypool for the first time:

“I met him about the time he was in grade six, riding that BMX around. He would stop in the school when we would have open gym and he would come out to play basketball.

“He grew out of that BMX dream by about grade eight because his knees were hitting his chin by that time and he went on to pursue other things.”

Lenz recalls quietly respecting the manner in which Claypool and his family dealt with their loss.

“It wasn’t something morbid or something Chase tried not to talk about. He sort of dealt with it in his own way.

“Yet in facing those challenges he really developed as a man. I really don’t know how you handle that as a kid. But somehow he was able to handle that kind of adversity.

“It did not make him angry, it made him want to prove something—that his sister meant something to him. He wanted to make sure that if she was there looking down that she would be proud of what he was able to accomplish.

“I think probably before people were making millions of dollars on the ‘challenge and discomfort equals growth’ scenario he was actually living that here.

“He’s actually a pretty special kid.”

Once Lenz got to know Claypool better, he noticed the tattoos on Claypool’s right arm.

They read, “A thousand words won’t bring you back. I know, because I tried. Neither will a thousand tears. I know, because I’ve cried. Until we meet again.”

“That’s why the tattoos are there—they are not there in any angry sort of way,” says Lenz.

“They are there in a real positive, challenging sort of way. Not everyone can take a situation like that and turn it into something that makes them better, to remember it but not dwell on it. I think he’s done a pretty amazing job of that.”

Claypool still worries about how his mother copes.

“Sometimes my mom is alone—it’s weird for me not to be there,” he says. “I’m sure she thinks about it, but she counts her blessings.

“I don’t think about it in a bad way. And I’m in the position I’m in now to make a difference. I think about focusing for four to six seconds on every play (in football).

“People are going through more than I am, and I’m doing this for a reason. I just try to forget the pain and fight through what I’m fighting through now.”

Lenz professes major admiration for Claypool’s mother:

“His mother did an amazing job. She was always here, but was never one of those parents that was overbearing. She led him in the direction he needed to go, whether it was academics or athletics, and she was incredibly supportive.

“I taught his older brother, too, but it was never one of those things where they wanted everyone to feel badly for them. They as a family unit dug in together and dealt with it in a really constructive way from an outsider’s point of view. I’ve seen other situations where people have not dealt with it that way and they’ve ended up bitter and angry.

“Chase has just accepted whatever challenges were there and looked for chances to get better.

"He has displayed an incredible amount of resiliency going through and dealing with all the things a young kid deals with.

“If we all could deal with all the challenges in his life the way he has, we’d probably end up a lot better. He grew up just down the block from our school. . . . He was able to come through with a different point of view—that he was going to make the best of whatever he was given and in the end he is doing that.”

Originally recruited by current Irish assistant coach Mike Elston and former assistant Mike Denbrock, Claypool came to the Irish as something of a diamond in the rough. In fact, for a long time he expected to be a basketball player at the collegiate level.

“Up until my senior year I thought I’d be playing basketball,” he says. “I was doing really well in that sport going into my junior year (he averaged more than 40 points per game as a senior) and I started getting looks and some small-time offers. I thought I could do it if I trained just for basketball because I was part of a good AAU program.

“Then my brother (Jacob Carvery who played football at the University of British Columbia) came to one of my basketball games and we talked about going to football. He was convinced there were some great opportunities out there if I stuck with that sport.

“Eventually I messaged my AAU coaches and told then I was going to do the football thing. Then I got an offer the very next week from (then) Nevada (head) coach (Brian) Polian (now an Irish assistant coach)—and now I’m here.”

Claypool came to the Irish Invasion Camp and also benefitted from an overall exposure standpoint when he attended The Opening in Beaverton, Oregon. The night before he signed his national letter of intent to come to Notre Dame, he scored 51 points in a high school basketball game.

“My family has never had an opportunity like this at the Division I level. My older brother was really good at football, but it was hard to get exposure. He’s shorter than I am, but I mirrored him in terms of how we play. I always watched his film on YouTube.”

Claypool says not a lot of people at Notre Dame know much about what happened with Ashley (she would have turned 23 in February).

“Maybe more people in my class—CJ Sanders has always been there for me.

“I actually think about it every day—especially when it comes to playing football.

“I think about it more now since Coach (Matt) Balis (first-year director of football performance for the Irish) came. He put us through some things where you just want to give in, and you’ve got to find a reason why you are doing something.”

Claypool, now a 6-4, 228-pounder, arrived in South Bend as a potential-laden raw talent. He broke into the Notre Dame starting lineup three games into the 2017 season, caught four passes for 56 yards in a win at Michigan State and then made his first career touchdown reception a week later at Notre Dame Stadium against Miami (Ohio). He earned a monogram as a rookie in 2016, mostly for his special teams contributions.

“She’s my reason,” he says. “I use it as something to motivate me.”

Claypool’s mother came to South Bend for the Irish home game in September against Georgia, and the two shared a spiritual moment on campus.

“We had been down to the Grotto before, but we never really went in there.

“I asked her if she wanted to go and light a candle.

“She said, ‘Think about lighting one for your sister.’

“And I said ‘Yeah, I was thinking about lighting one for her, too.’

“So we did that, and that was pretty cool.

“I liked doing that for my mom—she has gone through a lot.

“It still hurts her.”