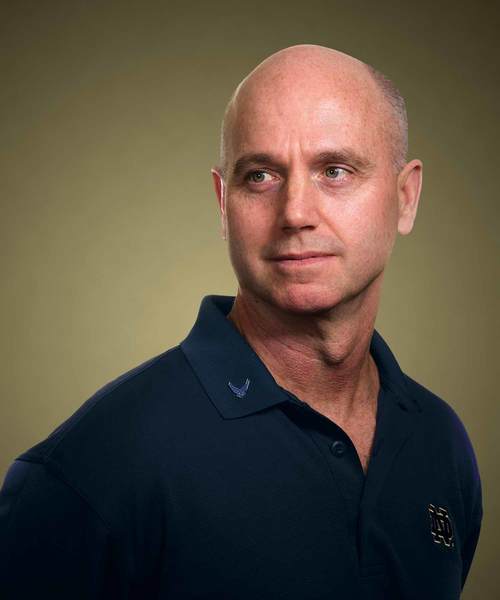

Dave Lucia

He coaches a special team

It had been three decades since Dave Lucia laced up the skates and took to the ice at the University of Notre Dame. A lot had changed since Dave played for the Fighting Irish.

Like the building, now the shiny, state-of-the-art Compton Family Ice Arena, as opposed to the beloved old barn on the north side of the Joyce Center. Until that recent hockey reunion game, Lucia (pronounced LOO-sha and no relation to the father and son Notre Dame hockey players Don and Mario Lucia) had only been back to campus once since he graduated and that was just for a quick show-around for his wife and two children.

It certainly wasn’t that he didn’t want to come back—in fact, he credits Notre Dame with making him the man he has become today—but he really did have better things to do. Like serving his country and, in the process, becoming a genuine American hero, even if that is an accolade he is almost loathe to accept.

God, Country, Notre Dame. Those are not just words on a new line of Under Armour T-shirts sold at the bookstore. That mantra, which former University president Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., used to define the core philosophy of the University (and chose as the title of his autobiography), represents the very words many Notre Dame graduates have followed to guide them through life.

The life Col. David Lucia has led could be another best-selling shirt: God, Country, Notre Dame and Family. And that would be a family of five—Dave, wife Lt. Col. Mildred Bonilla-Lucia (retired), daughter Erica, son David Raul and the United States Air Force.

Panama, 1989, Operation Just Cause is a war most Americans don’t remember unless they were in the middle of it, like then-Air Force Capt. David Lucia. He was the Air Force liaison officer to the 82nd Airborne and its mission was to parachute in and secure a strategic airfield so it could be used as a staging area to go after the defense forces of the brutal dictator Manuel Noriega.

It did not start out well. It was more like a mini-version of the start to D-Day. The troops were scattered all over, and Lucia landed on a fence. He had to extricate himself, only to find he was the senior officer in a band of brothers—and many of them had never met before. An operation that was supposed to be easy-in, easy-out under the cover of darkness was now a full-blown battle under a bright, enemy-friendly sky. Lucia and his newfound friends, many of them just 18-year-old kids, managed to hold the airfield. That is when it became dicey and dangerous.

They were ordered to go after Noriega’s troops, at times crawling toward a hill with bullets tearing up the tall grass and weeds and narrowly missing Lucia and several others. Then the enemy unleashed mortar fire. Lucia made the unilateral decision to call in air power, in hopes of sparing his men certain injury and death. He made the right call. They took the hill and Noriega’s troops fled.

When night settled Lucia witnessed something that has stayed with him through the years and solidified in his mind why he became a military man. In a small Panamanian village, people lit candles in their homes and came outside waving white flags to celebrate and to thank the Americans for what they had done for them.

In this case, the United States won the people’s hearts and minds. For his bravery, Capt. David Lucia was awarded the Bronze Star and the prestigious Lance P. Sijan Award, which recognizes leadership in the Air Force and is named for an Air Force captain who died while being held as a prisoner of war in Vietnam.

Those who knew Lucia well as a student (and an electrical engineering major from the Class of 1983) and hockey player at Notre Dame recall a young man who would mature into a leader of men and women. Former teammate Kirt Bjork, who now works in regional development at Notre Dame, says Dave was silky smooth on the ice with great hands and all the players wanted to be paired with him in practice because he made them look good when he seemingly never missed with a right-on-the-stick pass.

Dave qualified as a top-notch penalty-killer with an uncanny ability to disrupt the other team’s mad dashes up the ice. Lucia was always pensive and thoughtful, says Bjork, and spent more time in the electrical engineering library than he ever had to spend at hockey practice. No one wanted to sit next to him on the long road trips because he always had the bus overhead light on so he could do his homework.

It wasn’t all work and no play for Dave. Bjork likes to point out that Lucia once in a while could let his hair down (he had hair then) for a few hours at the old Corby’s and Bridget’s which, as all Domers from that era recall, helped to make for a more well-rounded graduate.

It is no pun to say Lucia’s Air Force career soared after Panama. He flew nearly 2,500 hours, 160 of them in combat. He has so many medals attached to his uniform that to list and describe them here would take up the rest of this publication. By 2008 he had become the senior military representative to the U.S. Department of State. Two years later an already brilliant career was one step away from the ultimate achievement—he was recommended for a promotion, one that could have led Dave to become a three-star general within a few years.

He turned it down and retired from active military service. By its very nature a military life often means precious family time is lost and David’s family situation by then required his full-time commitment. Mildred is also retired military, a maintenance officer, or as she puts it, “David broke airplanes. I fixed them.”

When son David Raul was 18 months old (he is 17 now) something happened so suddenly that Dave and Mildred thought he might have suffered a traumatic brain injury.

That wasn’t what happened. It was the sudden onslaught of severe autism. The family was now in a whole different kind of battle. It has been 15 years since their son’s diagnosis. In the last decade and a half, research on autism has provided a better awareness and understanding of the condition as well as recommendations for treatment.

That is why dad retired from the Air Force. He studied autism like he pored through those electrical engineering books at the Notre Dame library. He knew he could make a huge difference for his son and many, many other autistic children.

And how he does make that difference? Hockey.

The Lucias were better off than many other families with autistic children. They had enough resources to find good doctors and good teachers but, no matter how hard everyone tried, there were still those whispers that their son would always be an underachiever. Accept it and go from there. To the Lucias, and most other families, that obviously was unacceptable.

That’s when Dave turned to hockey and formed the Montgomery County (Maryland) Cheetahs, a team for kids young and older with special needs. That team then blossomed into a full-blown “league,” the American Special Hockey Association—and Dave is the executive director.

They have a most unique core philosophy when it comes to their brand of hockey.

“When we play our games the score is always tied. We are not about winning. Winning for us is about getting those kids on the ice and just having a good time,” is how Dave puts it.

But, don’t assume this is just a bunch of kids fooling around on the ice. The team has assistant coaches, as well as mentors from middle and high schools around the Montgomery County area. A 10-year-old boy on the team maybe summed up the experience for these kids the best: “I have so many friends now.” Is there a better bottom line in life than that?

Doors that were once closed to these youngsters are now open and they no longer have to constantly worry about being accepted. Hockey and Lucia became the roadmap to break out of a solitary world.

Just like those people in a small Panamanian village, the David Lucias of this world can win hearts and minds in many ways.

“When we leave this earth the only thing we will be measured by is what we gave,” he said.

David Lucia has already given a lot.

He still has a lot to give.