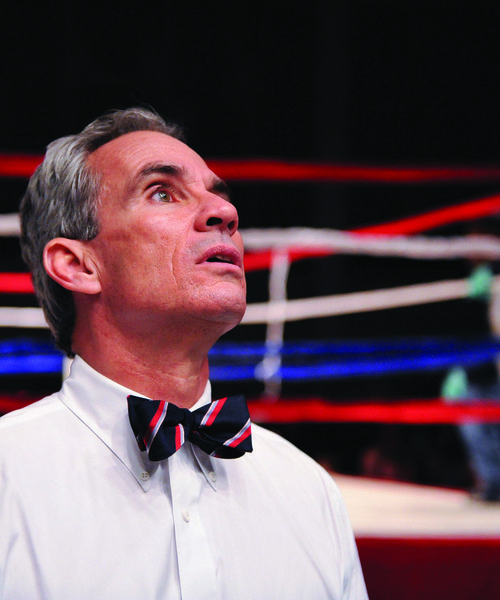

Mike Lee

A Bengal Bouts champion and so much more

In the course of establishing itself as a world-class university, Notre Dame has produced world-renowned figures in a wide-ranging realm of disciplines, from anthropology to zoology and most everywhere else in the alphabetical spectrum.

Mike Lee, a 2009 graduate, would like to add professional boxing to the list of fields in which the University of Notre Dame claims a preeminent prowess. His goal is to become light-heavyweight champion of the world.

In a way, it’s an incongruous mix. Notre Dame remains staunchly committed to its Catholic heritage, a religious institution first and foremost, faith and morals the uncompromising underpinnings of its mission.

Boxing’s “heritage” is a bit more unseemly. The corruption and double-dealing that formed the storyline in such movie classics as The Harder They Fall were uncomfortably accurate depictions of the sport’s culture. Don King and Mike Tyson aren’t the first fight-game luminaries to experience the inside of a prison cell.

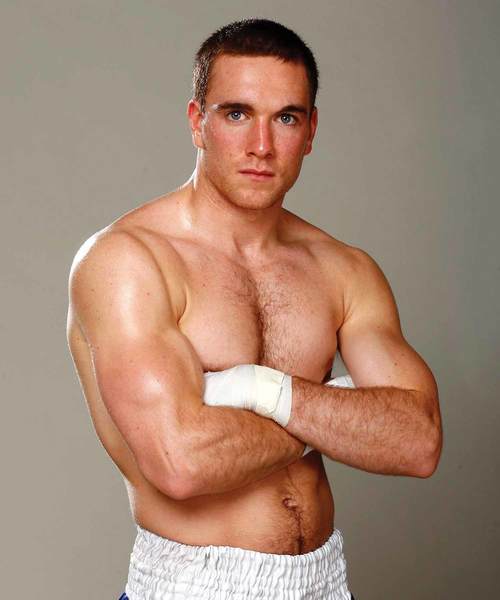

Prizefighting might not be a conventional career path for a 2009 honors graduate of Notre Dame’s Mendoza College of Business, but it’s the path that attracted Lee the first time he stepped into the ring as a teenager. He grew up on the none-too-mean streets of Wheaton, Ill., and was a two-sport athlete at Benet Academy in Lisle while playing club hockey on the side. But it wasn’t enough for him.

“I got cut from the sophomore basketball team when I was 16, and I was devastated,” Lee recalls.

“I was looking for something else. I’d always been an aggressive athlete, so my dad and my cousin took me to Windy City Gym. As soon as I got in the ring I was hooked. I loved the mental and physical toughness boxing requires, the discipline. It’s just you and your opponent in there. There’s no excuses, no relying on anybody else.”

Lee transferred to Notre Dame after a year at the University of Missouri and found a ready-made outlet for his passion in the Bengal Bouts, Notre Dame’s annual intramural tournament that draws hundreds of participants. He won the 175-pound championship all three years he competed. As a senior, he traveled to Chicago to test himself against tougher competition in the city’s prestigious Golden Gloves tournament. After fighting his way to the light-heavyweight title, Lee decided he was ready to turn pro.

“His background doesn’t hurt him. He’s a nice-looking kid, intelligent and he works at it,” says Sam Colonna, a longtime Chicago trainer who worked with Lee at Windy City.

“It’s too early to tell if he’s a real prospect, but he’s a sharp kid, and he’s learning.”

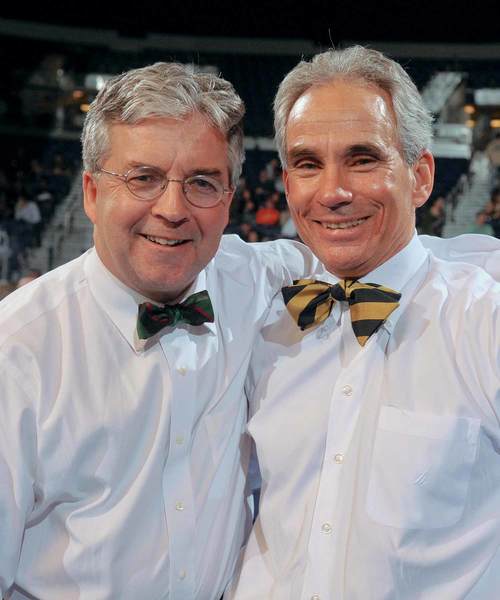

John Lee, Mike’s father, was an athlete himself, playing minor league baseball in the Minnesota Twins organization. He is fully supportive of his son’s quest as Mike’s manager, determined to do what’s best for him. To that end, Team Lee signed with promotional giant Top Rank, Inc., whose CEO, Bob Arum, has been a powerful force in boxing since Muhammad Ali ruled the sport. At Arum’s recommendation, they retained Houston-based Ronnie Shields as Lee’s trainer.

“I told Ronnie I’d be honored if he’d work with me,” Lee says, “and he asked me when I could be there. I said, ‘Tomorrow,’ and I was.”

Any skepticism Shields might have been feeling vanished after their initial meeting.

“I told Mike I only trained guys who wanted to be world champions,” Shields recalls.

“Mike said, ‘That’s why I’m here.’ I still wanted to be sure he was serious, so I put him through some hellacious workouts—he was throwing up, exhausted, everything. But he said, ‘I’ll be back tomorrow,’ and he was.”

Lee moved to Houston to work with Shields full time.

“He’s making good progress,” Shields says.

“He moves well and he has good power—everybody he hits, he hurts. He’s very intelligent, and he keeps his cool in the ring. He’s been in with some of the best guys we have down here.”

Some of them are more typical fighters: rugged, off-the-streets types who might resent Lee as an overhyped curiosity.

“Not at all,” Shields says. “They respect how hard he works. Plus Mike is a genuinely good guy. Everybody likes him. They’re helping me help him.”

There’s no denying that Lee’s anomalous background and Top Rank’s promotional muscle have opened some doors for him—six bouts into his pro career, Lee had already appeared on an ESPN Friday Night Fights telecast and on a Manny Pacquiao undercard before 30,000 fans at Cowboys Stadium in Texas.

His seventh fight—a four-rounder that took place Sept. 15—was his most enjoyable. The opponent, Jacob Stiers, was unremarkable, and the outcome, a victory via unanimous decision, was rather predictable after Lee put the Kansas City journeyman down three times.

The venue was what made the evening special: Purcell Pavilion in the Joyce Center on the Notre Dame campus. “It was like a dream come true for me,” Lee says.

With Lee the headliner, the card was Notre Dame’s first foray into professional boxing, and by all accounts it was a success, with a few thousand fans from the Michigan State pep rally joining a healthy contingent of Mike Lee backers.

“They were loud, they were crazy. I loved it,” Lee said.

He donated his entire purse to charity: the Robinson Community Learning Center, a Notre Dame-sponsored social-services agency assisting underprivileged families in the South Bend area, and the Ara Parseghian Medical Research Foundation.

Parseghian, the Irish coach from 1964 to 1974 who won two national championships, is still a revered figure on the Notre Dame campus. He established the foundation in 1994, after his three youngest grandchildren had been diagnosed with Niemann-Pick Type C, a cholesterol-storage disorder that occurs in children and often proves fatal by adolescence. Three Parseghian grandchildren died from the disease.

“Ara told me that when the kids were diagnosed with this horrible disease, he could sit back and accept it, or he could fight it—and he chose to fight it,” Lee recalls.

“That really made an impression on me. Ara Parseghian means so much to Notre Dame.”

The “giving back” nature of the program appealed to Notre Dame after Lee’s promotional team proposed it.

“Boxing isn’t something we’d normally align with, but Mike is a good guy, and he was really sincere about doing this to help others,” says Lou Nanni, vice president for University Relations at Notre Dame. “Plus, he chose two charities that we’re closely associated with.”

Lee delighted his backers by knocking Stiers down in the first, second and fourth rounds. He survived an anxious moment—and proved something to himself—when Stiers dropped him with a roundhouse right in the third.

“In a way I’m glad it happened. It showed I could come back,” Lee says.

The next day he was introduced to the crowd during Notre Dame’s victory over Michigan State, its first of the season. At halftime he got to meet several of the 1966 Irish football national champions who were back on campus for a 45-year reunion. Then it was back to Houston for more roadwork, more sparring, endless drills and drudgery, interspersed with the occasional shot at glory.

“Mike is doing what he needs to do to advance,” Shields says.

“He’s paying the price. He really wants to be good at this, so he listens, and he’ll try everything we put out there for him.”

Coryn Lee watches her son’s fights with “a mother’s normal concerns,” but she’s there for all of them.

“He’s always done the most dangerous thing in all the sports, so this isn’t really new for him,” she says.

“He was a catcher in baseball, a goalie in hockey, a quarterback in football. He doesn’t want to be that guy sitting around at 40 or 45 saying, ’I wish I would have done that.’ He’s going for it, and I’m behind him 100 percent.”

Lee is a tempting target for a promoter eager to exploit his unusual background—a white college graduate from affluent suburbia taking his shot in a sport known as a way up and out for the disadvantaged.

“I’d really like to get past the ‘great white hope’ talk,” he says.

“The guys I train with know how hard I work. I’m in the gym every day and not in the clubs or the bars at night. I’m 24 going on 64 when it comes to that stuff. I think anybody who’s seen me fight knows I’m serious. Once you’re in the ring, the last thing you’re thinking about is what color somebody is.”

Shields’ ring savvy and the parental instincts of Lee’s manager are safeguards against too much, too soon.

“Most young fighters lose fights they shouldn’t take,” John Lee says.

“We’re being very careful. This isn’t a career you pursue forever, but you can’t deny a kid who’s chasing a dream, and that’s what Mike is doing.”

Chasing it with as strong a commitment as ever.

“What is life if you don’t expose yourself to a little risk?” Lee says.

“If you had told me I’d be this far along 15 months from my pro debut, I’d say I exceeded my own expectations. When I’m 60, 70 years old, I don’t want to have any regrets.

“Even if I’m not a world champion, I’ll know I went for it.”