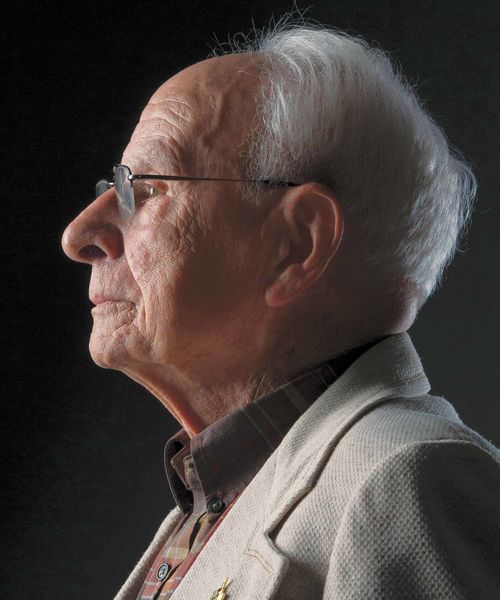

Sylvester Cashen

A labor of love

For the thousands of University of Notre Dame football fans who make the once-a-season long-haul trip to South Bend, many of them call it their yearly pilgrimage.

To make it worth their time, trouble and hard-earned cash the game itself is merely a main course surrounded by an a la carte menu filled with can’t-be-missed traditions.

There are so many of them that even those with the heartiest Fighting Irish appetites still have to pick and choose from the Friday luncheon to the pep rally with a bookstore stop in between.

That schedule is nothing compared to Saturday with a campus stroll, marching behind the band, greeting the players as they walk to the stadium, tailgating with your family and friends and after the game going to the spectacular candlelight dinner at the South Dining Hall. And, don’t forget, you can go to Mass with hundreds of others late Saturday or Sunday morning.

For some other fans, more than you ever would have imagined, there is another real pilgrimage to be made. To take this one you go west from campus on Angela, drive about two miles, turn right on Portage, go three more miles and then make a left. At that point it is important that you conduct yourself with a particular decorum because your journey has taken you to a cemetery.

It is next to impossible to overstate the persona of Knute Rockne. He was arguably one of the biggest figures in American sports in the 20th century alongside Babe Ruth and few, if any, others. And Rockne accomplished that in a much shorter lifetime and without a résumé that included many of the Babe’s indiscretions.

Whatever plateau Rockne had reached in Americana it was exceeded in his adopted hometown of South Bend where everyone just called him Rock. He pretty much owned the place but somehow always remained the guy next door, whether it was at the first family home on St. Vincent Street (a few blocks from campus, just off Notre Dame Avenue) or the tonier house on East Wayne Street on the east side where the family held a wake at the end.

The memories of Rockne in South Bend today can only be those that have been handed down now that we are more than three quarters of a century removed from that terrible plane crash in a desolate Kansas field.

That is where Sylvester “Cash” Cashen comes into the story. He was born a month after Rockne died, yet today is as close to anyone who could have personal memories. Cashen’s in-laws, the Petersons, lived just around the corner from the Rocknes in that Notre Dame Avenue neighborhood and the two families could not have been closer. How close? The day Rockne was buried at Highland Cemetery, Cashen’s father-in-law Clarence Peterson decided he would buy plots a few feet away so the two families would always be together.

Cashen lives alone now, not too far from the last Rockne home in South Bend—the love of his life, Mora Peterson, gone for more than a decade. He keeps busy, the best he can as a widower and a retired butcher who worked in the basement of Notre Dame’s North Dining Hall.

But it was more than a retiree’s desire to stay active that took Cashen one day two decades ago out to Highland Cemetery with a few tools and a lawnmower in his car. For whatever personal reasons, he had decided it was his duty to take perfect care of the Peterson and Rockne burial site.

There was only one problem. Highland, like most cemeteries, has a policy against individuals hauling out the heavy-duty tools because, after all, it is a place for peace and quiet and a battalion of Sunday morning yard-workers would make that impossible. Still Cash is a resolute fellow—stubborn might be a better word—and he somehow convinced Highland’s management to give him a dispensation.

And so for the last 20 years Sylvester Cashen has gone out to Highland at least twice a month from early April until the end of November when either the home season ended or the lake effect snows piled up. During the football season he tries, as best he can, to go out every Monday after a home football weekend because that is when there is a lot of work to done.

For many years after Rockne’s death there were several myths about what happened to the body, almost conspiracy theories. The one that made the most sense was that the body had been moved to the cemetery at Notre Dame at the quiet request of University higher-ups. The most outrageous was that some kind of international dust-up had occurred and the body was exhumed and taken in the dark of night to a plane and flown back to his native Norway. Neither are true, and Rock remains now and forever in his beloved South Bend.

You have to do your homework to find the actual burial site or luck out and find a staff member who will show you, because there is a stone memorial to Rockne and his family just off to the side of a road and that is where many tourists think it is but it isn’t. While the memorial is a lovely touch, it is not what the family wanted. The Rocknes came from simple roots and they wanted to keep it simple. The grave marker, like hundreds of others at Highland, just has a name, the dates and the word “Father.”

But Rockne’s funeral was no simple affair at Notre Dame or in South Bend. The University and the town were in shock and consumed with grief, there is no other way to describe it. You can go online today and Google “Knute Rockne’s funeral” and find pictures that are stunning. Outside Sacred Heart Church (now the Basilica) the crowd that surrounded the funeral procession cars appears to be 10 to 15 lines deep and in the streets of South Bend parents had to hold their children on their shoulders so they could get just a glimpse of Rock’s last ride.

Sylvester Cashen got all of these stories firsthand from his wife’s family members who did not have to wait in line or even in a large crowd of onlookers because Knute’s wife Bonnie wanted them at her side throughout it all. So you can see why Cash takes this personally and says he will keep going out to Highland until the day someone takes the car keys away from him.

The graveyard routine has remained pretty much the same for the last 20 years. In the early spring, around Mother’s Day, Cash buys flowers and goes through his annual planting and fertilizing ritual and then tends to them throughout the summer when he spends three to four hours at a time meticulously caring for the plots of both families. He brings the groundskeepers donuts and they loan him a lawnmower.

And he talks to Knute Rockne. Crazy? Well, if he is, he has a lot of company and there is plenty of evidence to prove it. On those Mondays after a football weekend the scene is surreal. Everything from cigar butts to shot glasses to empty whiskey bottles are there, along with numerous candles that have left wax all over the grave markers. It is no wonder the Highland staff decided to let Cash take care of the place.

But there is something else left that, at first glance, would seem mysterious. There are coins in every denomination. Now what could that be all about? Cash isn’t sure, except he has noticed over the many years that the stipend is much larger when Notre Dame is not playing well. The only conclusion he could reach is that fans come out to ask Rock if he might come up with a few plays that would turn the team around.

Sylvester “Cash” Cashen was out there this season and already is making plans to plant the flowers and mow the lawn beginning next spring. He will probably take a look at a plot of land just a few feet away from the Rock.

That is where Cash will be buried next to his beloved Mora and not far from the legend whose legacy he has very much helped keep alive.