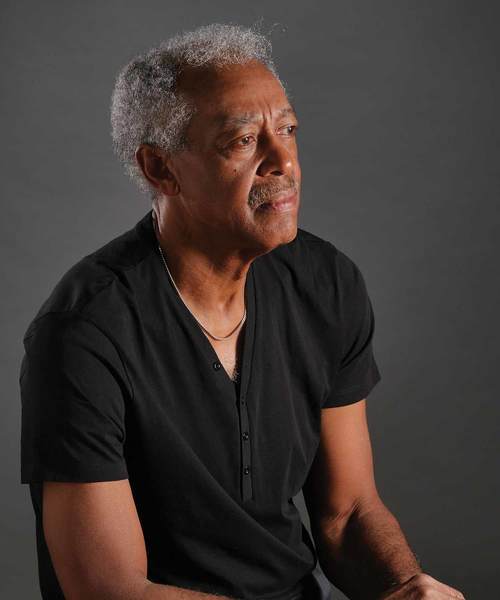

Thom Gatewood

Lots more than football

Stephen Studer is a prominent South Bend attorney as well as an alumnus of the University of Notre Dame.

A few years ago Studer (a 1973 graduate) was making his way toward Notre Dame Stadium on a game day when someone introduced him to former Irish wide receiver Golden Tate.

Surprised at the NFL player’s diminutive stature in person, Studer said, “You can’t be Golden Tate.”

“I am,” said the former All-American and 2009 Biletnikoff Award winner.

“If you’re Golden Tate,” asked a still dubious Studer, “who’s Thom Gatewood?”

“I dunno,” he replied.

That Tate, who held the school’s single-season receptions record for one year (Michael Floyd broke it in 2010), failed to recognize the name Thom Gatewood, who had held the same mark for 36 years, is not shocking.

Sure, Gatewood played nearly two decades before Tate was born and his brief NFL career with the New York Giants was unremarkable, but that is why Tate was unaware of him. The man whose 157 career receptions stood as the Fighting Irish record from 1971 until 2006 has never courted celebrity.

As a high school sophomore in Baltimore, Gatewood starred on a junior varsity squad that went both undefeated and unscored upon—and through the entire season his parents never knew he was on the team.

“My parents would not have let me play because they were serious about academics,” says Gatewood, who was a straight-A student at Baltimore City College High School. “I spent the whole season lying about after-school activities.”

Studer, who was Gatewood’s roommate in Keenan Hall, accepts his friend’s anonymity as part of Gatewood’s legacy.

“Thom is a naturally humble person,” says Studer, who was not a varsity athlete. “When he visited the Playboy Mansion as part of the All-American team his senior year, all he told me was, ‘Hey, I’m going outta town.’”

“Thom and I had been dating a few weeks,” says Susan, a savvy Michigan State alumnus, “before I finally asked him if he had ever played football. ‘Yes.’ Did you play in college? ‘Yes.’ Did you play in the NFL? ‘Yes.’ When I asked him why he hadn’t told me earlier, he said it was because he didn’t want me to think he was a ‘dumb jock.’”

Gatewood was a National Football Foundation Scholar-Athlete recipient at Notre Dame. He spent all eight semesters in South Bend on the Dean’s List. He overachieved in the classroom and on the gridiron and he has always been uncommonly humble in discussing his accomplishments.

“I’ve always wondered,” says his good friend, Studer, “if Thom felt that he deserved all those accolades.”

The story begins on Ashburton Street in West Baltimore, in a two-story, three-bedroom row house. Tom (he added the “h” later in life) was the second of Thomas and Wilhelmina’s six children. His mother, schooled in the value of education, quizzed him with flash cards and organized frequent trips to the library. His father taught him by example.

“My father was a blue-collar guy,” says Gatewood. “He worked six days a week and on the seventh he’d go help out on my grandmother’s farm.”

Thomas Sr. always kept his work boots on the foot of the stairs. If his son needed something, a little spending money, for example, he would write a note and leave it inside one of the boots.

“When I got older and had money of my own,” says Gatewood, “I’d leave a few dollars for him and a note: ‘Here, Dad, grab a cup of coffee.’”

Baseball was Gatewood’s first love—he would be drafted by the Philadelphia Phillies as a teenager and he parked cars before and after Orioles games at Memorial Stadium. But when a few friends decided to try out for the junior varsity football team at Baltimore City College High School, he tagged along.

“There were 600 boys trying out for the team,” Gatewood recalls. “We’d march up one by one to a man sitting behind a desk with a clipboard and he’d ask us what position we’d like to play.”

Gatewood replied, “Wide receiver.” The man at the desk was George Young, the football coach and a history teacher at the school. Young would later go on to become the general manager of the New York Giants and assemble their first two Super Bowl-champion teams.

In Gatewood’s first season of organized football as a sophomore, he starred on a team that never allowed a point. In his junior year, as the team was in the midst of the first of two consecutive state championship runs, recruiting letters arrived by the dozens. One of his sisters would intercept them before his parents saw them. He was still afraid to share his secret.

Midway through Tom’s junior year, Thomas Sr. was having a conversation with a customer.

“Gatewood?” the man asked. “You wouldn’t happen to be related to that kid from Baltimore City College High? The football star who’s always in the papers?”

“The jig was up,” says Gatewood, smiling and shaking his head as he tells the story. “But it was okay by then. I already had 50 scholarship offers, so I knew my parents would not be that upset.”

In an era before scouting services and YouTube videos, Gatewood received more than 200 scholarship offers. He was wooed by the most legendary coaches in the game’s history, from Bear Bryant to Joe Paterno to Woody Hayes to Bo Schembechler, the last of whom promised, “I’ll change my offense for you.” So unsophisticated was Gatewood that he flew cross-country to visit UCLA one weekend, then retraced the route the following week to visit USC.

On his maiden flight, to Los Angeles, a flight attendant asked what he’d like for dinner. Gatewood declined to order because he thought he’d have to pay for it.

“No one in my family had ever been flown before,” says Gatewood. “I might as well have been the Wright brothers.”

It was the winter of 1968. In Westwood Gatewood watched two UCLA basketball games featuring Lew Alcindor on the court and coach John Wooden on the bench. One week later he was at USC, where his student host was O.J. Simpson.

As Gatewood’s eyes were being opened to the perks of being athletically desirable, Young was clandestinely corresponding with Notre Dame. He had put together a highlight reel and sent it to coach Ara Parseghian. Young had no intention of telling Gatewood, who was raised Methodist, about his plan unless the Irish showed interest in his player. They did.

“George took me aside and said, ‘Before you make a decision, I want you to visit Notre Dame,’” Gatewood says. “George knew my personality. I was really shy and academics were important to me.

He thought a smaller school would fit me better.”

Gatewood visited in February. Whereas student hostesses had awaited him at LAX, South Bend presented him with a blinding snowstorm. All that Parseghian offered, besides an education, was a second dry-cleaning coupon since football players were expected to dress formally more often than typical undergrads.

“When I asked Thom what Ara offered him to come to Notre Dame,” says Studer, “he’d say, ‘Nothing. That’s why I came.’”

When Gatewood reminisces about his years at Notre Dame, he speaks more passionately about conversations he had than he does about the two Cotton Bowl games versus Texas, the latter of which saw the Irish topple the top-ranked Longhorns. He glosses past the record-setting 77-catch season in 1970. Instead, he talks about the moments that forever shaped him. Conversations.

The first involved a chance meeting with a teammate, offensive tackle George Kunz, at St. Joseph’s Hospital in South Bend. It came near the end of a disappointing first semester on campus.

“When I first arrived at Notre Dame in the summer of ’68, they handed me number 44,” says Gatewood. “I thought, ‘That’s an odd number for a wide receiver.’”

It was. Parseghian and his staff had decided that the 6-2, 200-pound Gatewood, potentially the fastest player on the team, would play running back. He had never played the position. He had never coveted it. As freshmen were ineligible to play varsity at the time, Gatewood spent that first autumn on the scout team, posing as the opposition’s marquee running back.

“Earlier that year I was O.J. Simpson’s guest on a recruiting trip,” says Gatewood, “and now I was pretending to be him in practice.”

It was a rude and physically tortuous introduction to college football. After breaking a finger in practice, Gatewood was dispatched to the hospital. He was homesick. Unhappy. Teetering. In the waiting room, Gatewood found himself seated next to Kunz, a 6-5, 260-pound senior offensive lineman who was there because of a separated shoulder.

“What’s wrong with you?” asked Kunz, a team captain in the middle of an All-America season.

“I’m not sure I belong here,” Gatewood confided.

“How are you doing in school?” asked Kunz.

“Dean’s List,” said Gatewood.

Kunz sat up taller.

“That’s three-fourths of the reason you’re here,” said Kunz, who was also a National Football Foundation Scholar-Athlete. “You’ve lost your faith. You have to look inside. See who you are. Look inside your heart. Have a conversation with God. Then make a decision and don’t look back.”

Gatewood decided to do two things. First, he decided to stay. Second, he decided that he was going to play wide receiver. Listed seventh on the depth chart at running back that spring, Gatewood begged Parseghian to move him to wideout. One day Parseghian put Gatewood at split end and told his junior quarterback, Joe Theismann, to throw Gatewood a deep ball. He caught it. Again, said Parseghian. By the end of spring practice, Gatewood had not only found a new position, but Parseghian had discovered a new offensive philosophy.

“We tailored our offensive philosophy based on the talent pool we had,” says Gatewood, whose 7.7 catches per game in 1970, his junior year, remain a school record. “That was part of the genius of Parseghian.”

In September of Gatewood’s sophomore year, another conversation would render a permanent imprint. He was doing homework in Keenan Hall one night when the phone rang. The voice on the other end of the line belonged to Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., the University's president. Hesburgh asked Gatewood to visit him in his office.

“When the president calls you in,” says Gatewood, “you think, ‘What the hell did I do?’”

Hesburgh had not summoned Gatewood to talk about misconduct. Or football. He wanted to discuss, in the autumn of 1969, race relations.

“Father Hesburgh basically spoke to me as if I were Jackie Robinson,” says Gatewood.

The priest who had marched with Martin Luther King Jr. implored Gatewood to appreciate, on a campus that was approximately one percent African-American, how valuable he was.

“We would like young people to want to be like you,” said Hesburgh, mindful that he was not only preaching to a football player but also a Dean’s List student. “You’re an ambassador. Where you go, we go.”

A few weeks later Notre Dame traveled to New York City to play Army in Yankee Stadium. Thomas and Wilhelmina Gatewood were in the stands. It was the first football game they had attended.

“They had no idea what they were watching,” says Gatewood, who would catch 10 balls, two of them for touchdowns, in Notre Dame’s 45-0 rout of the Cadets. “Then the crowd began chanting my name, and I think they enjoyed that.”

Gatewood would go on to catch 157 passes in three seasons as Notre Dame’s starting split end and Theismann’s favorite target. That total, as well as his 77 receptions in 1970, were Notre Dame marks that lasted for 36 seasons until Jeff Samardzija topped them in 2006. Gatewood, though, prefers to compare himself not to Samardzija but rather to Kunz, the upperclassman who once gave him a pep talk.

“We both were team captains, we both were first-team All-Americans and we both were national scholar-athletes,” says Gatewood, who neglects to mention that he achieved those feats as a pioneer of sorts.

“I love Thom Gatewood,” says retired Notre Dame sports information director Roger Valdiserri. “Thom taught me more than I taught him. Thom taught me how to act around black athletes. Thom taught me what it was like to be black.”

In an era when many football programs (including a few that had recruited him) were still segregated, Gatewood stood out as the first African-American skill-position player in the history of the nation’s most renowned football powerhouse. When the Irish traveled to Atlanta to face Georgia Tech, the hotel told Parseghian that Gatewood could not stay at the hotel. The crowd at Bobby Dodd Stadium threw Coke bottles at Gatewood and teammate Clarence Ellis, a defensive back, and opposing players directed slurs at them.

“Our teammates would tell us, ‘Don’t worry, they hate us, too, because we’re Catholic,’” says Gatewood, chuckling. “That didn’t make us feel any better.”

Still, Gatewood relished his ground-breaking role. Both he and Ellis scored touchdowns in that 38-20 Irish rout. Five weeks later, as the Irish took the field at the Cotton Bowl for the school’s first bowl game in 45 years, Gatewood caught a 54-yard touchdown pass against the top-ranked, segregated Longhorns team. As he sprinted toward the end zone, Gatewood raised a fist in the air, the one time perhaps on or off a football field that he ever unduly called attention to himself.

“To do that in Texas, against Texas, I understood what that meant,” says Gatewood. “The politics of college football at that time, if we got two nationally televised games, plus a bowl game … I wanted younger kids to watch and think, ‘If that black kid can do it, so can I.’

“Texas didn’t have a black player,” says Gatewood (the Longhorns would win that day and be the last segregated national champion), “but I like to think that (future Longhorn Heisman Trophy winner) Earl Campbell may have been watching that game.”

These days Gatewood is still a role model to a young generation. In the well-manicured gated community of row houses where he and Susan live in Nutley, New Jersey, he spends his afternoons giving tennis lessons to children. Gatewood is not a certified tennis professional, but he is still in peak condition. About 10 years ago, a parent saw Gatewood hitting balls to his wife, who is white, and assumed that he was her tennis instructor.

“He asked me if I gave lessons,” said Gatewood. “I said, ‘Sure.’”

Now “Coach Thom” has 43 tennis students, perhaps none of whom have any better idea of what No. 44 achieved under the Golden Dome than Golden Tate did.

And Gatewood remains laconic around family members about his accolades.

Two years ago, as Thom and Susan were watching television on a winter night, Thom’s phone rang. He took the phone into the other room.

“Being a good wife, I turned down the TV so that I could eavesdrop,” says Susan, “but he was gone for so long that I eventually gave up.”

The caller had been someone from the College Football Hall of Fame, calling to inform Gatewood that he had just been inducted, the 45th such Notre Dame player to gain that distinction.

When Gatewood finally returned, he looked at Susan and simply said, “I’m in.”