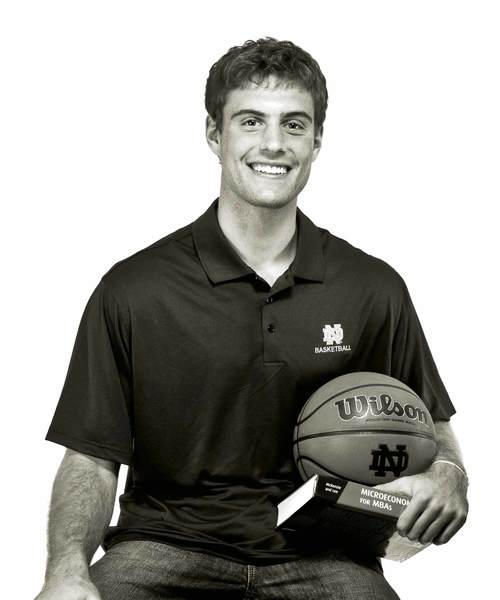

Tim Abromaitis

He hits the daily double in combining athletics and academics at Notre Dame

Decades ago, before the Notre Dame basketball team was playing in the Purcell Pavilion, before the Joyce Athletic and Convocation Center was even built, even before the long-since demolished Notre Dame Fieldhouse was erected, the University of Notre Dame made a name for itself by doing what others said couldn’t be done.

It wasn’t just that Notre Dame’s basketball program was an underdog in the days before the Irish won Helms Foundation national championships in 1927 and 1936; the entire University’s identity and tradition was steeped in the role of the underdog. When the original administration building burned to the ground in April 1879, University founder Rev. Edward F. Sorin, C.S.C., boldly announced that a new and bigger replacement would be built; the current familiar landmark opened in time for the fall semester that same year.

Of course, Notre Dame’s iconic football program carved out its unique place in sporting lore by knocking off the giants of the college football world in the first quarter of the 20th century.

Indeed, Notre Dame became the world-renowned institution it is today because men and women figured out a way to accomplish things that nobody else thought possible.

These days, Notre Dame is a marquee name. Whether world-class faculty and educational facilities, a first-of-its-kind contract with NBC Sports to broadcast every Notre Dame home football game for more than two decades, and championship-caliber teams in over two dozen sports, with state-of-the-art arenas and stadia to match, Notre Dame is rarely thought of as an underdog in the 21st century.

So, perhaps, Tim Abromaitis is a throwback.

Electing to accept a scholarship to play basketball at Notre Dame after weighing offers from Northwestern, Penn and William and Mary, Abromaitis saw just 40 minutes of playing time for Notre Dame as a freshman in 2007-08.

That’s not what people usually mean when they refer to a “one-and-done” player in college basketball.

When practice started the following October, Notre Dame head coach Mike Brey, mindful of a deep group of junior and senior forwards on his roster, asked the 6-foot-8 Abromaitis to consider sitting out the 2008-09 season. That would mean Abromaitis would completely forgo playing time that season, while preserving a season of eligibility for the future.

In making the case for taking the season off as the ’08-’09 opener approached, Brey told his young player, “If we played tonight, maybe you’d play seven minutes.”

Those are hardly the kind of words a young competitor wants to hear. But Abromaitis sought the counsel of his mother Debra, his father Jim, who played at the University of Connecticut and in the NBA, and his brother Jason, who played varsity basketball at Yale. A few days later, Abromaitis told Brey that he would go along with the plan.

There were 602 days between March 22, 2008, when Abromaitis played one minute in Notre Dame’s NCAA tournament loss to Washington State, and Nov. 14, 2009, when Abromaitis was the first man off the bench for the Irish in their season-opening victory over North Florida.

A lesser man might have simply bided his time, marking off the days until he could inherit the playing time owned by the older players. Pragmatism may have led some student-athletes to devote themselves exclusively to studies, seeking more immediate victories than basketball would now provide.

Abromaitis used every one of those days to prepare for his junior year, on and off the court—and what a year it was.

In March 2010, he was named honorable mention all-BIG EAST after averaging 18.2 points per game, sixth best in the BIG EAST during conference play. In May 2010, he was awarded his bachelor’s degree in finance and also was recognized as the BIG EAST’s Men’s Basketball Scholar-Athlete of the Year on the strength of his 3.8 grade-point average.

Abromaitis’ seemingly sudden emergence as one of the best players in one of the most competitive basketball conferences in the country likely came as a surprise to most casual basketball fans.

“My parents and brother weren’t surprised, and my teammates and coaches weren’t surprised, but just about everybody else was,” says Abromaitis.

But casual fans weren’t the only skeptics. Abromaitis had more than a few doubters while making his college choice.

“It took an awful lot of guts for him to decide to go and play at Notre Dame,” says Jason Abromaitis,

“when there were a lot of people that were telling him that he wasn’t that kind of player.”

Of course, given Tim Abromaitis’ makeup, those skeptics were all but assuring his success with the Irish.

“In a word, losing,” says Jason when asked what makes his younger brother tick. “We used to play everything in our front yard, and I was of the mindset that I would never let him beat me.

“I didn’t just want to beat him, but I didn’t want to let him score. Of course, that’s come back to haunt me now,” he says, chuckling.

Jim and Debra Abromaitis and both of their sons—in three separate conversations—all volunteer a story involving a hockey stick.

“We were playing something and Tim got mad and started chasing me with a hockey stock,” relates Jason. “My father was just standing there, watching, laughing and thinking to himself, ‘Let’s see how this will end.’”

Tim did catch Jason and got in a few harmless body blows with the stick.

“We got rid of the hockey stick shortly thereafter,” reports Debra.

That competitiveness isn’t limited to the basketball court.

Instilling a desire on the part of their sons to compete academically was no accident on the part of Jim and Debra.

“It’s more a credit to our parents,” says Jason, who earned his degree from Yale and is now a managerial consultant.

“The boys looked at athletics the same as academics,” says Jim. “What do I need to do to be the best?”

Already mindful that Jason, who is four years older than Tim, was in rarefied academic air, Debra recalls Tim’s mindset as he prepared to take a grade-school spelling test.

“He turned to me and asked, ‘What did Jason get on this test?’” Debra remembers. “He just wanted to be sure that he did at least as well as Jason did.”

At Notre Dame, where seven Academic All-American men’s basketball players preceded him, Tim nonetheless has distinguished himself even among such scholar-athletes. None before him graduated in three years and embarked upon the rigorous accelerated master’s of business administration program in which Abromaitis is currently enrolled.

He never considered a more pedestrian academic path, even when Brey wondered whether Abromaitis might have been biting off more than he could chew.

“This summer when it was getting pretty grueling I got him in my office and said, ‘I need to ask you something—is this too much for you? Because if it is, we’ll bag this right now,’” recalls Brey, who may as well have been waving a red flag in front of a bull.

Abromaitis’ response to Brey’s concern was firm, but typically low-key —“No coach, I’ll be all right.”

“And he’s handled it great. He’s amazingly competitive and he’s fearless,” says Brey, echoing the theme sounded by Jason.

“When he is stuck or challenged, he always finds a way,” says Jim.

Along with fearlessness and competitiveness, there is another quality in Tim Abromaitis that is impossible to miss—humility. Listening to his parents, it’s equally impossible to miss the source of that humility. As Jim and Debra speak with unmistakable pride about their two sons, they share credit with many others—including extended family, teachers, guidance counselors, youth sports coaches, neighbors, older teammates at Notre Dame, and Brey and his coaching staff.

That humility has allowed Abromaitis to become even more than an incredibly rare academic and athletic superstar. Starting with his brother, he learned how to compete as hard as possible, and then leave the competition on the court or in the classroom.

“As much as we fought, as competitive as we were, I remember my uncle telling us that he knew we were going to be close,” recalls Jason. “It sounded weird at the time, but he was right.”

“My brother is my best friend,” says Tim. “He’s the smartest guy I know and we are competitive in everything.”

And maybe because Abromaitis knows what it’s like to have people tell him he’s not good enough, he’s learned to be an encouragement to others. He does so quietly and without fanfare, as anyone who knows him would expect.

He provides friendship and inspiration to a high school classmate struggling with special needs and helps a college roommate forge ahead after a promising athletic career was ended by a devastating high school injury that also resulted in permanent disability.

Tim Abromaitis, who seemingly thrives on being told he can’t do something, makes a point of urging those less fortunate that they can succeed.