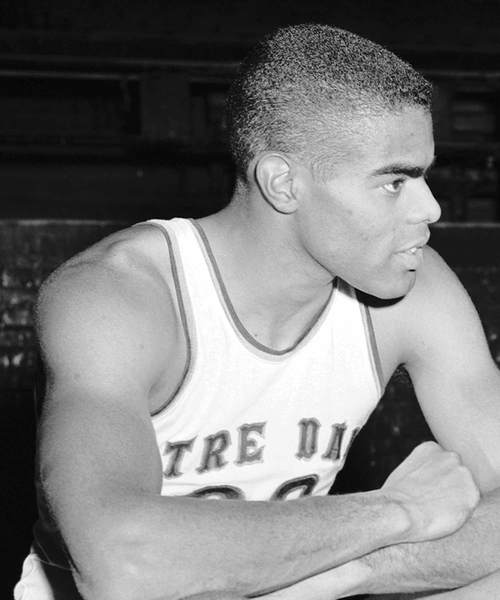

Tommy Hawkins

Breaking barriers at Notre Dame

Because he has lived a proudly unconventional life, it stands to reason that Tommy Hawkins would choose a rather unconventional method of telling his life story: a book of poetry.

Life’s Reflections: Poetry for People was released in the spring of 2012 and has nearly sold out its initial printing. Works by some of his artist friends, including the late LeRoy Neiman and Ernie Barnes, accompany each chapter.

“When you say ‘poetry,’ most people go to sleep,” Hawkins says. “But this is a narrative in which you will find yourself, your family and your friends.”

The book was “decades in the making,” Hawkins says, tracing its roots to an English literature class he took at Notre Dame more than 50 years ago.

Canterbury Tales, Hawkins says. “Father (Chester) Soleta, our professor, told us it would ‘live in our souls,’ and it did. That phrase was the inspiration. I wanted to write something that would resonate with people.”

Hawkins’ compelling story might resonate with people if it were printed in crayon, or scrawled out on a cocktail napkin. The son of a single mother growing up on Chicago’s South Side, he was both a basketball star and an ambassador charged with promoting racial harmony at Parker High School (now known as Robeson) as the surrounding neighborhood underwent the occasionally testy process of integration in the mid-1950s.

Hawkins had led the Chicago Public League in scoring and had grades to match his basketball achievements. With dozens of college scholarship offers to choose from, he signed with Notre Dame, knowing he’d likely be the only African-American player on his team and, as it turned out, the only African-American student in his class.

“My life has been about breaking barriers,” Hawkins says.

He was 10 years old when Jackie Robinson transformed sport by breaking the “color barrier” in Major League Baseball, not too young to be affected by a society-altering development.

“I wanted to step through the doors Jackie Robinson opened and have others follow me,” Hawkins says. “That’s been my role in life.”

Notre Dame had a fortunate “in” with Hawkins as the recruiting process was getting under way. Ed O’Farrell, his coach at Parker and the closest thing to a father figure in his life, was friendly with Irish coach Johnny Jordan, even though they had competed at rival South Side high schools. O’Farrell arranged a meeting with Jordan while the Irish were in town to play in a doubleheader at the old Chicago Stadium, and a campus visit sealed the deal.

“I think I was there about 10 minutes and I called my mother and said, ‘Tear up the list—I’m going to Notre Dame,’” Hawkins says. “The place just reeked of aura and tradition. It was like sports Shangri-La, and I knew I’d get a great education. Where do I sign?”

A dynamic, athletic leaper who played bigger than his listed height of 6-foot-5, Hawkins remains one of the most decorated basketball players in school history, 53 years after graduating with a degree in sociology. He was Notre Dame’s first African-American All-American and first African-American team captain. He is ninth on the Irish career scoring list with 1,820 points and third in scoring average with 21 points per game. He remains Notre Dame’s career leader in rebounds with 1,318 and is second in rebounding average with 16.7.

“There’s a photo of me being introduced in a spotlight at the old Chicago Stadium that’s my favorite,” Hawkins says. “Loyola had beaten Kentucky on a last-second shot in the first game of the doubleheader, and the place was up for grabs—22,000 people. Then we beat North Carolina in the second game, the year after they won the national championship. I scored 35, and I was named Chicago Stadium player of the year.

When the stadium closed, they came out with those ‘Remember the Roar’ T-shirts. I remember it that night.”

The Irish were 56-26 in Hawkins’ three varsity seasons, going 24-5 and reaching the NCAA Championship’s Elite Eight in 1957–58. That was the best showing in school history until a Digger Phelps-coached squad advanced to the Final Four 20 years later.

A first-round draft pick of the then-Minneapolis Lakers in 1959, Hawkins played 10 NBA seasons with the then-Cincinnati Royals and the Lakers after their move to Los Angeles. His teams made the playoffs each season, and his teammates included some of pro basketball’s legendary names—Elgin Baylor, Jerry West, Oscar Robertson, Wilt Chamberlain. Hawkins complemented their high-scoring talents by tailoring his own game to provide whatever was needed.

“I wasn’t playing much my rookie year with the Lakers and Bob Pettit was just killing us one night,” he says. “Jim Pollard was our coach. He looked down the bench, and he seemed to be looking for someone who could stop Pettit. ‘I’ll take him,’ I said, and he put me in. I wouldn’t say I shut down the great Bob Pettit, but I made him work for it, and as time went on I developed a reputation as a defensive specialist.

“I thought if I could average 10 points and 10 rebounds a night and do the job on the other team’s big scorer, I’d be contributing. No matter what the stats said, I wanted the coach to be able to come to me and say, ‘Hawk, you were the difference tonight.’”

Jordan had seen in Hawkins a future communicator. He not only suggested he take public speaking courses at Notre Dame, be brought his star player along on some of his own speaking engagements so Hawkins would be comfortable talking in front of people. When broadcasting presented itself as a second career option as his playing days were winding down, Hawkins was ready.

He was the first African-American analyst to work at the network level when he teamed with Curt Gowdy for five years of college basketball broadcasts on NBC Sports, including Notre Dame’s epic 71-70 victory over UCLA that ended the Bruins’ record 88-game winning streak on Jan. 25, 1974.

Hawkins was a high-profile media personality in Los Angeles, serving as KABC Radio’s sports director for 14 years and KNBC–TV’s evening sports anchor for four. He didn’t limit himself to sports, co-hosting morning news shows on KHJ–TV and KABC for a combined six years. He also indulged his first love—jazz—with a weekend gig playing his favorites at KXGO Radio.

In his “spare time” Hawkins taught a sports/sociology course at Cal State Long Beach. And when Major League Baseball was shamed into examining its minority hiring practices after Dodgers general manager Al Campanis’ infamously insensitive remarks about black athletes’ qualifications, Hawkins took the lead in performing damage control. He went to work for the Dodgers as their director of community relations and helped a forward-thinking franchise repair its reputation. He also convinced some of his ballplayer friends to consider staying in the game after their playing days so baseball would have a deeper pool of talent to draw from as it sought to increase its minority presence beyond the playing field.

Hawkins wound up spending 18 years with the Dodgers. As a vice president, he was the highest-ranking African-American in baseball for a while.

“Not everybody welcomed me because I was this basketball player going to work for a baseball team, but I had a message to deliver,” Hawkins says. “It was unfortunate that the team of Jackie Robinson found itself in that situation. It had to be fixed.”

Hawkins was never one to back away from a challenge, a trait he developed as a youngster and honed at Notre Dame.

“My father wasn’t in my life and I didn’t want him in my life,” he says. “I had to grow up a little faster than most kids in my situation and be the man of the family at a young age, but that was all right.

I came to the realization that life is vast. There were a lot of intervening variables that helped me become a man in a man’s world.”

Despite his distinctly minority status, Hawkins treasures his Notre Dame experience.

“In my four years, I didn’t have one morning where I woke up and dreaded being there,” he says. “I felt included in everything.”

Two incidents stand out. In his freshman year, Hawkins took a date to an off-campus pizza place that was a favored spot among Notre Dame students. The proprietor asked if he had a reservation. Hawkins, of course, did not—reservations at a pizza joint?—and was denied service.

When word of the snub reached Paul Hornung, the newly minted Heisman Trophy winner proposed a student boycott of the place until Hawkins received both guaranteed service and an apology for his troubles. Both were forthcoming.

“Paul Hornung was a big man on campus with a lot of influence,” Hawkins says. “He didn’t have to get involved like that, but he did.”

During Hawkins’ sophomore year, the Irish were invited to New Orleans to defend the Sugar Bowl Tournament title they had won the previous season. But they were invited with one stipulation: Because of segregation laws in effect throughout the South, Hawkins would have to stay in a different hotel, one that served “colored.”

This rule was unacceptable to Hawkins’ teammates. When their offer to stay in his hotel was rejected, they voted against playing in the tournament. Jordan backed their decision, as did Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., when the matter reached the University president’s desk. Hawkins was grateful, and not surprised.

“I remember Father Hesburgh saying, ‘Wherever a Notre Dame minority student isn’t welcome, Notre Dame isn’t welcome.’ That was huge. He was such a great leader.”

For as much as Hawkins enjoyed his Notre Dame experience, it wasn’t exactly multicultural. “I think 10 of the 12 guys on the basketball team were Irish,” he says with a smile.

There was an upside to that for a noted music lover. “I probably have the largest collection of Irish music of any black man in the world,” Hawkins says.

There was an upside to that, as well.

“We were in Dublin for St. Patrick’s Day with the KABC morning show in 1981, and we were getting in a cab to go back to our hotel. The cabdriver was sort of looking me over, and Ken Minyard, one of the show’s co-hosts, told him this big, black guy was Irish.

“He says, ‘Be gone with you—he’s not Irish,’ and Ken said, ‘I’ll tell you what: You name any Irish song you can think of, and my friend will sing it.’ ’’

After three verses of “Did Your Mother Come from Ireland?” delivered in a rich, melodic baritone, the cabbie was convinced. And the fare was on him.

A free cab ride was one of many benefits Tommy Hawkins gleaned from his time at Notre Dame.

“The blinders came off,” he says. “Too many of us walk around with blinders on. It impacts your vision.”