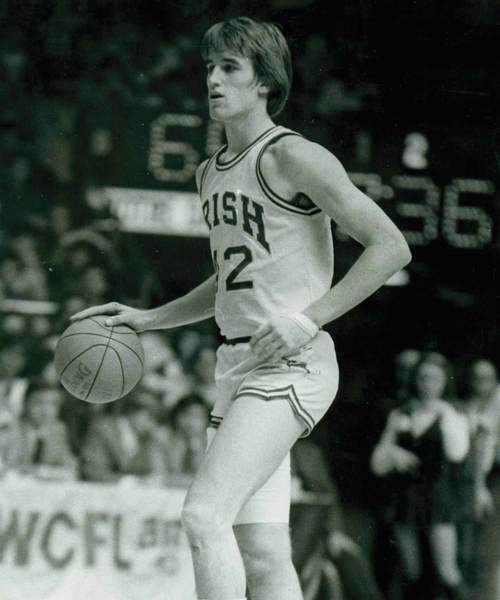

Bill Hanzlik

Makes his sport his service

It’s been nearly 33 years since Bill Hanzlik last pulled on a University of Notre Dame basketball jersey, but following the 55-year-old Hanzlik around for a just single day would make it pretty easy to figure out exactly what kind of player he was for the Irish, even without the benefit of ever having seen him play.

Ray Baker didn’t meet Hanzlik until “Hanz” was traded to the NBA’s Denver Nuggets two years after the Seattle Super Sonics had made Hanzlik their first-round draft pick in 1980. The two quickly forged a friendship that eventually gave rise to the Gold Crown Foundation, a Denver-based charity that has enriched the lives of thousands of youngsters and their families.

“Bill has an uncompromising way of giving,” says Baker. “He neither expects, nor anticipates, nor cares about receiving anything in return. That’s how he lives his life, by recognizing what needs to be done and doing it.”

Baker’s description of Hanzlik as a champion of children aptly describes Hanzlik as a basketball player.

Hanzlik had enough physical talent to play 810 regular-season and playoff games over 10 NBA seasons, but chose to become Notre Dame’s defensive stopper. The 6-foot-7 guard stifled post players, lightning-quick point guards, and everything in between—helping the ’77–’78 Irish to the only NCAA Final Four appearance in Notre Dame men’s basketball history.

He simply recognized what needed to be done, and did it.

Shortly after joining forces, Hanzlik and Baker decided that what needed to be done was to provide a basketball camp for girls. So they did, and Gold Crown Foundation was born.

“When we first started to do this, there was no grand scheme,” says Hanzlik, a member of the 1980 U.S. Olympic men’s basketball squad. “It was just a feeling that we’ve been pretty blessed and wanting to try to find a way to give back and to help out.”

When budgetary cuts forced the elimination of many junior high basketball programs in the Denver area, Gold Crown Foundation started what became the largest junior high basketball program in the state.

Scratch off another thing that needed to be done, now done.

A few years later, the Foundation led efforts to build a new youth baseball stadium, and Coca Cola All-Star Park, modeled after Denver’s Coors Field, opened in 1998.

And in 2003, the foundation christened the Gold Crown Fieldhouse. The 56,000-square-foot facility not only hosts basketball, volleyball and other sports, but also allowed the establishment of Gold Crown Enrichment, which offers educational enrichment activities to low-income families.

Done, done and done.

Brittany David was one of the first to participate in the Gold Crown Computer Clubhouse in 2004.

“I was a self-conscious seventh-grader with a hectic childhood,” she says. “I was at a point that I felt that the world around me had just collapsed. At that moment, I had so much pent-up emotion and no creative outlet to set it free.

“I instantly felt like I had been saved,” Brittany says. “Every day at the clubhouse was a new experience that I looked forward to. I love coming here and making friends—I didn’t have any friends when I first came here. None of the kids in my neighborhood liked me.”

Gold Crown staff encouraged Brittany to try drawing, triggering a remarkable transformation.

“I wasn’t creative before,” she says. “But I know I’m a great artist now because I have this great support system here telling me that I’m a good artist and helping me see how I can become an even better artist.”

Brittany became the first Gold Crown Enrichment participant to earn a college degree, and next fall she’ll enroll at the prestigious Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design to study illustration. She’s also the first in her family to receive a college diploma.

“I wasn’t a good student in grade school,” she says. “In middle school it got better, and in high school it got even better.

“In college, I got a 3.8 GPA,” she says. “It’s hard—it’s not easy. But I had people here telling me that I could do it.”

Brittany clearly has learned the most valuable lesson of all—she’s giving back as a mentor at Gold Crown.

“There’s a girl who’s almost exactly like I was,” she says. “That’s crazy! I see so much of me in them, and I just want them to get as much out of Gold Crown as I have gotten out of Gold Crown.”

Bill Hanzlik’s fingerprints—and not just his name—are all over Gold Crown.

“Gold Crown Foundation isn’t just something Bill has his name on and gets credit for,” says Gold Crown’s executive director, Kevin Petty, a former youth participant in Gold Crown athletic activities. “He’s here 60 hours a week, he lives it, he breathes it, serving pizza, shooting hoops, running around with the kids. It’s his passion.”

Although they were already extremely close, Baker got a deeper insight into Hanzlik during the 1997–98 NBA season, when Hanzlik coached the Nuggets to an 11-71 record, right in the middle of a drought of eight consecutive losing seasons for the franchise.

“I saw him coach probably one of the worst teams ever in the NBA and I watched him deal with that adversity, and I probably admired his integrity and character more than at any other time,” says Baker.

“He held himself accountable, even though he didn’t need to; he never blamed anybody else,” Baker says. “I sat through those press conferences and he never once lost his composure or his respect for anybody.

“He went through a tough time in his life, never blaming anybody or saying anything bad. And I think that carries over to how he treats kids. We’re blessed because he’s that way with our foundation. We have 26,000 kids and he treats them all the same, unconditionally.”

Brittany David experienced at Gold Crown precisely what Baker describes.

“Gold Crown is a great opportunity to let your creativity come through and be yourself,” she says. “In society, it’s really hard to get that—but here, they just let you be yourself, with no prejudices, no judgments.”

With so many children being profoundly impacted by Gold Crown Foundation, when Hanzlik contemplates the question that has guided the foundation since its inception: What’s best for the kids? recognizing what needs to be done next is simple.

“We have to have an exit strategy,” Hanzlik says. “If Ray or I get hit by a bus, we’ve got to find a way to keep this alive.”

Not surprisingly, the people who have worked with Hanzlik have no question that ensuring the long-term health of the foundation will become one more thing on Hanzlik’s “done” list.

“He is a matchmaker for ideas and resources,” says Katie Tiernan, the executive director of the Jefferson Foundation, which honored Hanzlik with its 2012 Crystal Globe for Distinguished Service. “He also is ridiculously positive, seeing opportunities instead of challenges. The word ‘no’ doesn’t seem to fit in Bill’s vocabulary.”

And then Tiernan echoes a familiar theme: “If something needs to get done, he just does it.”

Despite his Catholic upbringing, Baker never had a particular affinity for Notre Dame until he met Hanzlik, who met his wife, Maribeth, while the two were students at Notre Dame.

“We tease him about the only nauseating thing about him, which is his undying loyalty to Notre Dame,” says Baker with a laugh. “We know how much he loves Notre Dame, and you love that loyalty. You want to create that in your family, in your kids and in your culture.

“I’d never admit this to him, but there’s probably some of Notre Dame here,” he says. “He’s the perfect Domer. They care so much about each other. The foundation carries that—you can see how much they care for Bill and more important, how much they care for the children.”

With their four children—Meghan, Mollie (both Notre Dame graduates), Robby and Gillian—raised and off on their own, Bill and Maribeth are devoting their lives to their shared passion—helping children. Maribeth, who earned her master’s degree in social work at St. Louis University, is the executive director of Seeds of Hope (seedsofhopetrust.org), a non-profit organization dedicated to supporting Catholic elementary and high schools serving the low-income, minority population of inner-city Denver.

When asked about his legacy, Hanzlik seems a little taken aback. After a long pause, he answers on his own terms.

“I wouldn’t even use the word ‘legacy,’” he says. “What my dream would be is that the Gold Crown Foundation continues to grow and help kids more and more.”

Baker, who Hanzlik calls “one of the most influential people in Colorado that nobody knows unless you’re the governor or the mayor of Denver,” offers a fitting legacy for Hanzlik.

“He’s a very devout Catholic and he believes he’s here for a mission, and he lives that mission every day,” says Baker. “God put him on earth to be a giver, and that’s what he does.”