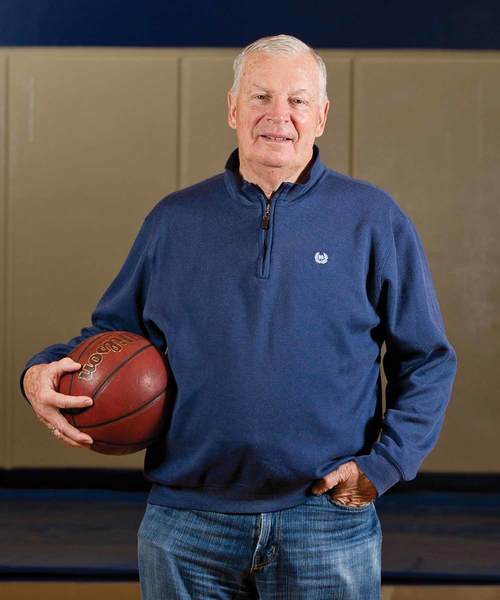

Digger Phelps

A Local Commitment

When Richard “Digger” Phelps stepped away from his position as University of Notre Dame head men’s basketball coach after the 1990–91 season, he didn’t stay away from his chosen sport for long.

Two years later he worked the NCAA Championships for CBS Sports and within a year he signed a contract with ESPN. Nineteen years later he remains a staple with ESPN’s popular College GameDay show that travels from campus to campus on winter Saturdays.

But, allow basketball to define him?

No chance.

Even when he was coaching at Notre Dame Phelps dabbled in painting and art. His interest in world politics led him, for a time, to keep a chalkboard in his Joyce Center office on which he listed his own plans for achieving world peace. He kept his fingers in an old-school hobby as a member of the Citizens’ Stamp Advisory Committee.

Soon after leaving coaching, Phelps went to work for former President George H. W. Bush as head of Operation Weed and Seed, a $500 million program that was part of the Office of National Drug Control Policy. It was designed to weed out inner-city drug problems and seed those same neighborhoods with programs that would make a difference in lives of local youth. The program had its successes, but it never made the cut when Bill Clinton was elected president.

In 1993 Phelps served as an observer for elections in Cambodia.

But it’s in his hometown of South Bend that Phelps has gone “all in.”

First, he took on South Bend schools, advocating for improvements in facilities and in the education commitment in general.

“Every 26 seconds we lose a kid out of high school somewhere in the United States,” Phelps says.

So the Beacon, N.Y., native fought not only to make the school buildings themselves more appealing for students but also for tougher academic standards for student-athlete eligibility.

At Notre Dame, all 56 of his scholarship players received their degrees. On the streets of his hometown he found the challenges to be different.

“I ran into a couple of area high school football players and I asked them how their grades were and one of them told me he had two F’s,” says Phelps.

“He was eligible to play with two F’s. I couldn’t believe it.”

Instead Phelps pushed adoption of a 2.0 grade-point average with no F’s for eligibility.

In 1998 he convinced the South Bend Community School Corporation and the South Bend Rotary Club to sponsor a program to revitalize Lincoln Elementary School in South Bend. The initiative included $200,000 in physical and after-school program improvements—boosted by the assistance of 800 volunteers on a June Saturday.

Why Lincoln? It qualified as one of South Bend’s oldest schools and had not been scheduled for renovation for another decade.

The end results? Landscaping, new dropped ceilings, lighting, windows—plus a fresh coat of paint for the auditorium and a new scoreboard. NBC’s Today Show even came to do a live early-morning report. Phelps helped set up after-school programs in subjects like cooking, stamps and creative writing.

Digger’s plan? It was simple. Provide the youth of the South Bend with more appealing school alternatives and you help fight increased violence, drug use and dropout rates.

For more than a dozen years Phelps has collaborated with Meijer and WNDU–TV in South Bend and Benton Harbor, Mich., to provide back-to-school backpacks and school supplies each August.

He returned from working the 2012 NCAA Final Four to local headlines highlighting youth violence, including the shooting of five youths in a 10-day period as part of three separate incidents.

Phelps led a spring Town Hall meeting, pushing ways for residents to use education to ward off violence. He enlisted more than 400 individuals to help mentor troubled local youth. He’s not afraid to challenge kids who may be headed the wrong way. He pushes them to use their athletic abilities to grab the education they need to be successful.

The result? A Stop Youth Violence program that Phelps envisions will feature mentoring as well as upgraded neighborhood watch and community policing efforts.

After Hurricane Katrina leveled much of New Orleans, Phelps used his personal funds to build two new homes. He points to creation of a $35 million FEMA grant that will turn John McDonough High School in New Orleans into the city’s first culinary high school.

“The model here is to motivate people to make a difference in kids’ lives. There’s no excuses,” says Phelps.

“There are 50 programs now that are community assets that the superintendent of schools, Dr. Carole Schmidt, can point to in the South Bend area. A great example is the Robinson Center on Eddy Street—a place where Notre Dame has been involved for a long time. It’s amazing to see the Notre Dame students who have taken Shakespeare come to volunteer at the Robinson Center, teach Shakespeare and at the end of the year the kids are doing Shakespeare.”

What do we do about dropouts? Phelps points to George Azar who runs the Rise Up Academy in the old Eggleston School on Adams Road in South Bend.

“If you’ve got trouble in math, or trouble in English, don’t drop out. Rise Up will help prop you up.”

He points to former Concord High School principal Rob Staley who created the Crossing Education Centers, programs to provide vocational skills and potential GED degrees to kids who had dropped out of school.

John McCaskill, merchandising and retail rep of Kraft Foods in Northern Indiana, has made a great case for hiring Crossing trainees with the applicable vocational skills.

Phelps, on a summer evening last July, met Larry Whitmore who was part of a group of 30 youths playing basketball at the Hammes Notre Dame Bookstore. Phelps called an impromptu “team meeting” and told the story of Bernard James, who joined the Air Force for six years, became a staff sergeant, eventually went to a community college, then to Florida State and at age 27 became an NBA prospect (now with the Dallas Mavericks, he was the 33rd pick in the 2012 draft).

“They all want to live the dream. Larry’s 24, and we’re trying to find a way to get him into a junior college or maybe IUSB. Use basketball as the hook.”

One local 17-year-old attended two different local high schools for periods of time, but he’s had more than one serious brush with the law, landing him in South Bend’s Juvenile Justice Center.

“I met with him and his probation officer. I said to him, ‘Where’s all your friends now?’ He’s on probation for a year and we’re trying to get him into another high school because he’s got two years of athletic eligibility left. Again, use sports as a hook,” says Phelps.

“The model involves finding these young men and saying, ‘Here’s a way to do this.’ We’ve now got him telling the 13-, 14-, 15-year-olds what they have to do to keep this from happening to them.

“Get a model for the community and show how we can go neighborhood by neighborhood. Have a picnic for the kids before they go back to school. If we’re going to get rid of violence the neighborhoods have got to get involved and show these young kids that there’s a better way.

“If they think violence is the only way, that’s what they’re going to do. Show them 10 options where violence is only one of the 10 and show them why to choose the other nine.”

Phelps hasn’t forgotten a chance meeting with former Notre Dame president Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., some years after Phelps left coaching. The former Irish coach had no qualms about his after-coaching career path, but Hesburgh made it clear he was less than impressed.

“That’s it?” Phelps remembers Hesburgh asking him. And Phelps hasn’t forgotten the tone of his former boss’ implication. It’s the same sort of challenge Hesburgh once issued to former El Salvador President Jose Napoleon Duarte, a 1949 Notre Dame graduate.

“Hesburgh does that to you,” says Phelps.

“He got me from coaching basketball to coaching the streets, coaching the game of life. I’m a Hesburgh disciple.”

His Irish teams 14 times played in the NCAA Championships, including the lone Irish Final Four appearance in 1978. Seven times his Irish upset top-ranked opponents, including the end of UCLA’s 88-game win streak in 1974. And along the way no one ever accused Notre Dame’s 419-game winner of being “wishy-washy” about anything.

Now, he’s simply changed his focus from matchup zones and free-throw percentages—to improving local priorities when it comes to topics like education, mentoring and gang violence.

Challenge kids to do something to make their lives better. That’s Digger’s mantra.

The city—and schools and youth—of South Bend have been the beneficiaries.