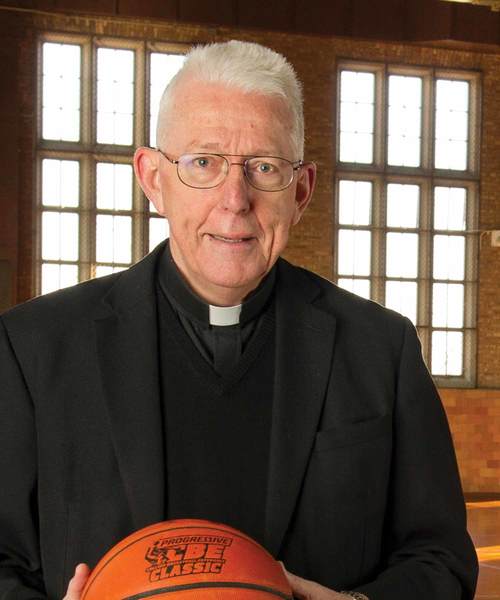

Edward A. “Monk” Malloy

From Hoops Star to President

Vince Lombardi once famously said that “leaders are made, not born,” but the inspiring life and times of Rev. Edward A. Malloy, C.S.C., would seem to belie that notion.

From his earliest years, Father Malloy—or Monk, as almost everyone calls him—has assumed the mantle of leadership—as a fourth-grade altar boy at Saint Anthony’s Parish in his hometown of Washington, D.C., to the “Mayor of Turkey Thicket” in middle school, from class president at Archbishop John Carroll High School to hall president in Badin Hall at the University of Notre Dame, to, ultimately, president of the University itself.

Born seven months before the United States entered World War II, Father Malloy was raised in a family of modest means in the Brookland neighborhood in northeast D.C., the oldest child and only son of Edward and Elizabeth Malloy. Monk’s dad was a claims adjustor for the D.C. Transit Company, and his mom worked in the home raising her son and two daughters, Joanne and Mary, for many years before then taking jobs with the U.S. Catholic Conference and the Catholic University of America.

He acquired the nickname Monk in the fourth grade as a rhyming rejoinder by a neighbor who was nicknamed Bunk. He early on became a sports fan, following the Washington Senators and Redskins with devotion. But it was basketball that became his game of choice. He spent so much time on the courts of the nearby Turkey Thicket playground that his friends eventually made him its “mayor.”

In the first of his three-book autobiography, Monk wrote: “If someone asked then or today what experiences of basketball were the most enjoyable for me, nothing would surpass the hours upon hours of pickup games at Turkey Thicket and around the network of playgrounds in the metropolitan area.”

All of those hours playing both pickup ball and in summer leagues paid off in high school. As a starter at shooting guard from his sophomore year on, Monk was part of one of the greatest prep basketball teams in history. Carroll was a very good but not great team in his sophomore year, finishing with a 22-3 record. Then, in his junior and senior seasons, the team combined for a record of 52-1, winning the city championship in the latter in front of more than 8,000 fans at the University of Maryland’s Cole Field House. The newspapers of the day proclaimed Carroll the No. 1 high school team in the nation.

Three years before the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling, Carroll opened in 1951 with the intent of being a racially diverse school. Father Malloy writes in his autobiography that the school and the basketball team—which included John Thompson, later the coach at Georgetown—were examples of “integrated cooperation and friendship” that helped represent the “hopes and dreams of a city at a time of major social transformations.”

An excellent outside shooter and student, Monk was pursued by numerous universities seeking to award him a grant-in-aid to continue his basketball career. He narrowed his choices to three—Notre Dame, Villanova and Santa Clara—and decided on the Irish after a recruiting visit in the spring of his senior year.

“All my intuitions during my visit told me that this was the school for me,” he says.

A fairy tale would have him go on to much success in the collegiate ranks, but the reality is otherwise. Freshmen were ineligible for varsity competition at the time, and in his sophomore and junior years, Monk saw limited action. As a senior, he played somewhat more, but in the end he says his basketball experience was “undistinguished and full of frustration.”

In some ways, however, that was a blessing. His lack of playing time led him to take on other activities available at Notre Dame, including student and hall government, and thanks to the teaching and mentoring of faculty members such as Don Costello and Joe Brennan, he developed an even deeper passion for learning.

“On occasion during my years under the Dome, I would imagine how things might have been if I had pursued one of my other scholarship offers,” Monk wrote in his autobiography. “Yet even if I had played a starring role elsewhere, I would have missed out on the non-athletic part of the Notre Dame experience and all it has meant to me ever since. My college education was paid for, I made lifelong friends, I received an excellent education, and I discerned my life’s vocation. How lucky can a person be?”

Most important among the extracurricular activities was a service trip to Mexico during the summer between his junior and senior years under the auspices of Notre Dame’s Council for the International Lay Apostolate. While on a trip to the center of the country, Monk’s group stopped at the Basilica of Cristo Rey, where he found himself alone for a period of time while others went exploring.

“All was quiet and I soon found myself in a state of reverie,” he wrote in his book. “It was as though time stood still and all the cares of the moment had dissipated. I was at peace. How long I remained so disposed I cannot say. All I know is that I had a sudden and compelling sense that I was being called to become a priest.”

The certainty of that call remained upon his return to Notre Dame in the fall, and throughout his senior year of 1962–63, Monk began the process of entering the priesthood as part of the Congregation of Holy Cross, Notre Dame’s founding religious community. Upon graduating with a bachelor’s degree in English, he entered the Holy Cross candidate program in August 1963 and for the next several years experienced the life of a seminarian and earned two master’s degrees in English and theology. After his ordination as a Holy Cross priest in April 1970, he went on to earn a doctorate in Christian ethics at Vanderbilt University, where there now is a chaired professorship in his name and he was a member of the board of trustees for several terms.

Monk returned to Notre Dame on the theology faculty in 1974 and has been at the University ever since. In the early 1980s, he was among a handful of priests selected as potential presidential successors to Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., and for five years he served as a vice president and associate provost. In 1986, he became the first Notre Dame president to be elected by the Board of Trustees, and the following year he assumed office in what some would say was the unenviable position of following a legend. He doesn’t see it that way.

“I learned through athletics to like a challenge, not be intimidated by circumstances, and to have a degree of self-confidence that if I worked hard, things would turn out OK,” he says. “Ted left the University in good shape. I didn’t have to reduce the budget or fire people. Plus, I was an insider and knew a lot about the University. I never felt intimidated by the job, and I think my athletic background prepared me well.”

Father Malloy’s presidency, from 1987 to 2005, was marked by a rapid growth in the University’s reputation, faculty and resources. Faculty positions rose by more than 500, some 140 endowed chairs were added, the average SAT score of incoming students rose by 160 points, the endowment skyrocketed from $456 million to $3 billion, and financial aid grew from $5 million to $136 million annually.

Given his own experiences at Archbishop Carroll, as well as his father’s participation in the civil rights movement, Father Malloy placed a premium on diversity in the Notre Dame student body, and during his tenure minority student enrollment rose from 7 percent to 18 percent.

Following the example of his predecessor, Monk also made major contributions to projects and causes away from Notre Dame, including leadership roles with the Boys & Girls Clubs of America, Campus Compact, the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, the Points of Light Foundation, and service as a board member at Vanderbilt, Notre Dame, Saint Mary’s College, the University of Notre Dame–Australia, and the universities of Portland and St. Thomas.

He takes particular pride in helping to establish Notre Dame–Australia and the Center for the Homeless in South Bend.

“Notre Dame–Australia didn’t open its doors until 1991 and now it has 9,000 students on campuses in three cities,” he says. “It’s just a great success story. I don’t attribute that to me, because it’s had great leaders. But to found a Catholic university at this point in history, and to see the whole thing emerge and transform, it’s just amazing. It’s the only independent Catholic university in the country and is doing an extraordinarily good job.”

Creating the Center for the Homeless in downtown South Bend in the winter of 1988 “stands very high among the things I’m gratified about,” Father Malloy says. “It really has become a model for how to respond to the needs of the homeless population in every way. Not just in housing and feeding them, but in helping them get a new life. A lot of that is attributable to the cooperative relationship with the city and various not-for-profit organizations. But without Notre Dame’s involvement and the commitment to buy the facility and all of the extra things that have been done, it never would have succeeded.

“I take special pride in those two areas. They responded to a need and I’m proud to have been involved,” he says.

Of all his achievements, however, it was a very personal sacrifice he made later in his life that is perhaps most impressive and which will continue to make a difference nationwide.

In 2008, tests determined that Monk’s kidneys were a match for his sister Joanne’s son Johnny Rorapaugh, who had experienced severe kidney dysfunction two years earlier and had been on dialysis three times weekly. Monk volunteered to donate a kidney to his nephew, but several weeks prior to the surgery the process took on a twist when doctors realized that a man who had hoped to donate a kidney to his mother was a better match for Johnny, and, fortuitously, that Father Malloy was a match for the man’s mother.

In a four-patient procedure Aug. 11, 2008, Father Malloy donated a kidney to the mother and his nephew received a kidney from the recipient’s son. Now, four years later, Monk and Johnny are doing well and, according to latest reports, so are the mother and son.

“The kidney transplant went from being a theoretical thing that I used to take up in my courses in biomedical ethics, to a personal issue,” he says. “My original motivation was love for my nephew and the bonds we had as a family. But, as it turned out, it required me to give my kidney to someone I didn’t know in order for my nephew to benefit. In some ways, the four of us are tied together.

“As a result of being involved in this, I’ve given a lot of talks on organ transplantation and have met so many extraordinary people, including people who just donate a kidney with no relational motivation at all. The message I try to deliver is that I want to make the donation process seem less heroic and more ordinary. My conviction is that most of the people I know would have done what I did [if] given the same circumstances. To be an organ donor is a major decision because it’s major surgery and does put your life at risk, to some extent. I would put it in the company of major gestures of love. But I don’t want to put too much emphasis on it because a lot of people do comparable things and don’t get any recognition.”

It’s just the latest—and likely not the last— example of a life of humble leadership.