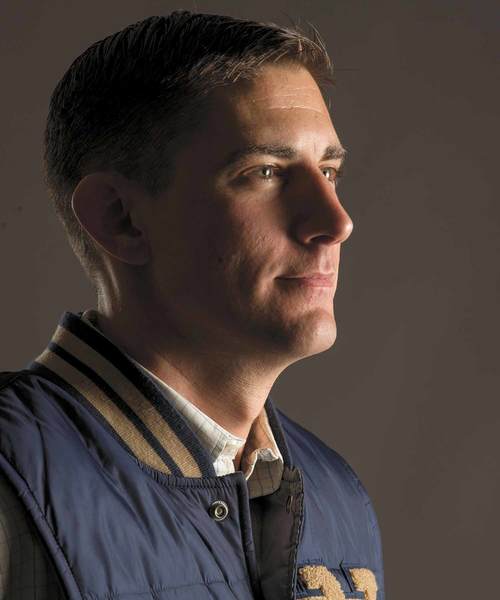

John Hiltz

Letting it fly

It was in the deepest dark of night, and U.S. Navy lieutenant commander John Hiltz had an f/a-18 to land.

The combat mission to support troops in Afghanistan—only his third since being deployed—had gone on for nearly six hours, but one last perilous task remained. We’re not talking about squeezing your SUV into a tight spot in the parking garage. We’re talking about flying in at maybe 200 miles an hour and then trying to hit one thin wire to get stopped on the deck of an aircraft carrier. It’s aiming for 300 yards of safety in the middle of a vast, black ocean.

That’s a degree of difficulty only a pilot could truly understand, especially this particular night on the carrier John C. Stennis. Let Hiltz explain.

“I was coming back to the aircraft carrier about one in the morning. I was the last pilot scheduled to land, and for whatever reason—mostly because I was new to it and I was tired—I just couldn’t land. It took me six tries to catch a wire and stop. There’s no more humbling feeling that knowing there are 5,000 people on that aircraft carrier and they’re just waiting for you to land.”

Scary, huh?

“The guys on the ground are in harm’s way all the time. They can’t fly away from trouble. I wasn’t scared in that sense. You just want to do a good job and make sure you’re part of a successful mission. That part is scary because the consequences of failure are great.”

Adventure, risk and, most of all, a sense of service. Meet John Hiltz, Notre Dame Class of 2002. There has been a lot of life crammed into his first 36 years.

He’s the guy who was a civil engineering graduate cum laude … and a fighter pilot … and a member of the famed Blue Angels. That flight path takes a man from patrols above a battlefield in Iraq to a flyover at Notre Dame Stadium. In one, he’s having to keep an eye out for enemy fire. In the other, he’s doing a maneuver 100 feet above the ground, flying four inches away from the next plane at 400 miles an hour. Either way, nothing—not a second of it—can ever be taken for granted. One mistake, one instant of lost focus, and the next moment could be catastrophic.

He’s the bone marrow donor who once helped a young man he had never met fight cancer. He’s the Bookstore Basketball shooting phenom for Keough Hall—and a walk-on guard for the 1999–2000 Irish men’s basketball team. That came after he was a heart surgery patient.

And finally, he is and always will be the son of Chris and Dan, who still live in the same house he grew up in back in Fort Mitchell, Kentucky, across the Ohio River from Cincinnati. Dan still goes to Jamaica every year to work on an orphanage. Brothers Jim and Greg both put in time in the military. It’s the family way.

“That’s just sort of what we are,”

John said. “We’re proud to serve.”

So where to begin?

Perhaps with the little boy looking at the model airplanes in his bedroom back in Fort Mitchell. But flying was not on his mind then. His passion was basketball. His dream was Notre Dame.

“When I was a kid, the only lullaby my dad would ever sing me was the alma mater,” he said. “I wanted to go to school at Notre Dame at all costs.”

The ideal would have been to come to South Bend as a basketball recruit, but he was a little short of Division I talent. So Hiltz came on an ROTC scholarship and did his basketball playing in intramurals—until his heart started racing uncontrollably. Turned out he had an electrical issue with his heart and needed surgery to correct the problem. Not the way most college freshmen spend their spring break. But he was back playing basketball in weeks.

“A minor inconvenience, overall,” he said.

He returned just in time to help unheralded Keough Hall to the finals of the Bookstore event, before losing to the team from the law school. Watching that day was Notre Dame men’s basketball coach Matt Doherty.

“Hey, Coach, I’d love to walk on the team next year,” Hiltz said to him.

“You’re skinny, you don’t play defense and you shoot too much,” Doherty answered. In other words, no.

But Hiltz went to a walk-on tryout the next fall anyway and made the team.

“Dream-come-true kind of stuff,” he said.

Okay, maybe, as he noted, that dream ended up sitting at the end of the bench most of the time, next to the trainer, strength coach and team chaplain. Feel free to imagine Rudy in short pants, but Hiltz pointed out the first time he actually got into a game—in the last minutes of a romp over Valparaiso—was not exactly Rudy-esque.

“I remember I got the ball in the corner to shoot. The student body always wanted to see the walk-ons play, and you could hear the crescendo of noise building as the ball came to me. It left my hand and you could literally feel the air come out of the building because the ball landed about three feet short of the basket. It was the biggest air ball I have ever shot. There was not the happy ending there.”

He played in three more games and scored six points in one of them. It was a wonderful experience, that sophomore season, but then Hiltz was off to the rest of his life.

“I wanted to have an adventure. I guess I have a type-A personality and I wanted to find a way to have the same experiences and team aspect I had on the basketball team,” he said. “You find that in F-18 squadrons. A team spirit, almost. That’s what drove me to aviation—that team spirit, the sense of adventure, the discipline to be good at it.”

He had one issue, though. Airsickness. Lots of it. You start doing turns and rolls at several hundred miles an hour and see what happens to your lunch.

“I got sick on my first nine flights,” he said. “It was getting to the point where, ‘If you can’t get over it, you can’t continue flying.’”

He consulted a psychologist, took pills, underwent hypnosis. Nothing worked.

“The only good advice I got was to try eating bananas. I said, ‘I’ve read all the books and done all the research and I’ve never read where bananas will help.’ They said, ‘Oh, it won’t cure airsickness. But at least it tastes like bananas on the way back up.’”

He eventually became acclimated and the problem went away for good. He was ready to be a pilot. But first, there was one more detour.

Hiltz lost three classmates at Notre Dame to cancer, and that painful reality inspired him to take part in bone marrow registration drive. He never really thought about being called as a match. Most aren’t.

But one day the phone rang. He had been found to match an anonymous cancer patient. Hiltz interrupted his training, went through the process of having his marrow taken and returned to active duty—not knowing the person at the other end of his donation. Until the message from Missouri.

“I’ll never forget. I landed from a combat mission and checked my email. It’s the middle of the night on the other side of the world and there’s an email that says, ‘Hey, I’m Drew Weiland. You don’t know me, but you saved my life.’

“It was two in the morning and I was still pumped full of adrenaline from flying a combat flight and landing on an aircraft carrier at night, and the tears immediately started coming down my face. It was such a full-circle moment, from losing three classmates here to signing up on the bone marrow registration and then having it actually work.”

So there he sat, a tough jet pilot, weeping to himself in the middle of the night and the middle of the Persian Gulf, a long way from home. They would later meet—Hiltz popped from behind the curtains as a surprise guest at a banquet honoring Weiland—and become friends. But not every story has a happy ending. That was 2006. Weiland’s cancer returned and he passed away in February of 2008 at age 24.

Weiland’s parents knew whom they wanted to deliver the eulogy at their son’s funeral. John Hiltz. He has maintained contact with them to this day.

“The confluence of events that led to all that I don’t think are coincidental,” he said. “They are all part of my Notre Dame experience. That led me to that.”

There would soon be another change in Hiltz’s life. He had long admired the Blue Angels and what they stood for with their air shows and precision maneuvers, giving the American public a glimpse into what goes on in naval aviation. A pilot needs 1,250 hours of flight experience to even be considered. Only two or three applicants are chosen each year, and while it is a great honor, it is also a risky one. Fewer than 300 pilots have flown with the Blue Angels and 26 died in accidents. That’s a fatality rate of nearly 10 percent, though many of the accidents happened in the early days, and the safety record has markedly improved.

It takes not only skill and experience to make the cut, but also convincing the other pilots you can be part of the team. One requirement is to tell a joke. Hiltz must have got off a good one.

“I’m not sure it’s ready for public consumption,” he said.

So the man who has seen combat missions by the dozens also spent three years with the Blue Angels. Imagine. Six roaring jets, as close as four inches apart.

“It’s an unforgiving business,” he said. “You get focused every day, every time. You do it whether it’s your first time or your 300th time.”

Easy for him to think back and pick his favorite flyover. That would be Nov. 2, 2013. Navy at Notre Dame. That was the campus he loved below him as he sped by, and he had to make very sure he didn’t get caught up looking for Touchdown Jesus. Flying as a Blue Angel does not allow much time for sightseeing.

“Beyond my wildest dreams,” he said of the moment. “It was a great opportunity to display to my alma mater the great things that men and women in the Navy are doing.”

One member of the Notre Dame community who understands that is Mike Brey. Hiltz arranged for the Irish basketball coach to hop a flight with the Blue Angels in 2014. How’d that go?

“An unbelievable experience,” Brey said. “When I was six months out, I said, ‘Oh yeah, definitely.’ But a week before the flight I was trying to figure out a way to get out of it. No one’s been more nervous.”

Just before the flight, they handed Brey—yep—a banana. He broke the sound barrier, did some barrel rolls and was able to last for 45 minutes—though he had to breathe his way back to normalcy when he started to lose some peripheral vision at 7 Gs. And he didn’t lose the banana, which was nice, since he was wearing a camera, and his players would have never let him hear the end of it. The pilot asked Brey if he wanted to go for 8 Gs. Brey answered that it seemed a fine time to quit when he was ahead and land.

“It was inspirational to be around that leadership, discipline, attention to detail—the same things we try to do with our program,” Brey said. So what’s harder, Hiltz’s job or trying to beat Duke in Cameron Indoor Stadium?

“Going into Durham and playing a game, that’s like going to Disney World,” Brey said. “In the plane, that was 45 minutes of anxiety, intensity, pressure. Games are a cakewalk compared to that.”

Hiltz was back on campus in October, taking in a basketball practice and attending the Navy-Notre Dame game—this time on the ground. He was scheduled to head back to the Middle East in November on the Harry S. Truman. Another carrier, another deployment, more night landings. No more air shows or football games. Now it’s for real again.

But some things never change for Hiltz. Fear, for one thing, though not the fear for his own safety.

“For most of my life, I’ve been driven by a fear of failure—not to be successful at a goal I have set for myself or someone else has set for me. I try to use that fear to drive me forward.”

What never changes is a sense of duty. That started in the house back in Fort Mitchell.

“The world is full of miserable millionaires and people who are successful but not happy. I think if you can find success serving others, that’s where you can find true happiness.”

What never changes is the attachment to his school and his service branch. He and they are bound for life.

“Those two institutions have certainly helped define who I am as a person,” Hiltz said. “When I signed up for the Navy, I said I would continue to be part of naval aviation as long as it was fun and rewarding and challenging. It hasn’t stopped being those things. I’m proud to put on the uniform every day. And I’m proud to say I’m a Notre Dame man.

“We’ll see where it takes me. I’m looking forward to the challenges ahead. But not too far ahead.”