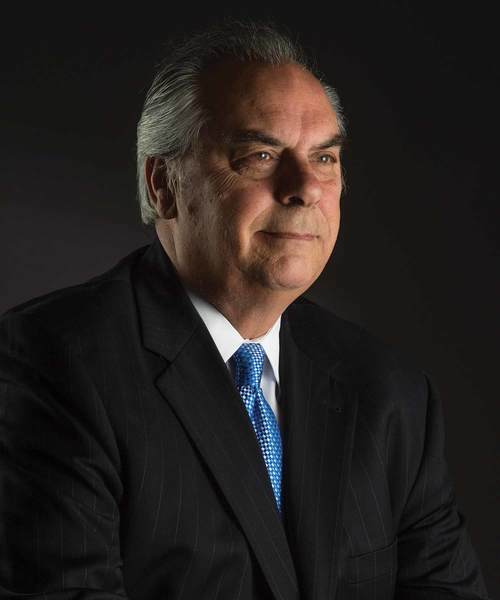

Ted Hesburgh

He set the standard

Try as you might, even at this point in life, you are not going to get former University of Notre Dame president Father Ted Hesburgh stuck in a quandary.

He can be frank, diplomatic, emphatic and thoughtful on any subject. But he’s never at a loss for what seems like the perfect answer to any question.

I have known Father Ted since several of us ran into him outside Cavanaugh Hall on the Notre Dame campus in November 1963, just days after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Those days still resonate with those of us who were on campus. Here we were at a Catholic university trying to rationalize the death of the first Catholic President.

Cavanaugh was a freshman dorm at the time and most of us were just a couple of months away from home for the first time—and the cloudy, cold and snowy South Bend winter had already started. It was depressing and the atmosphere not especially helpful in the classroom.

Father Hesburgh, who at the time was often falsely accused of being too remote and too concerned with matters away from Notre Dame, could not have been more accommodating to the rapidly growing group of students. He told us about his first days at Notre Dame and how he thought, more than once, that maybe, just maybe he needed to go home and rethink what he was doing. Here was the president of our University, explaining in a way even a freshman could understand, that there was nothing wrong with our feelings, and that as human beings it was all perfectly natural. We really needed to hear that.

Then Father Hesburgh opened the floor to questions, and I cannot recall if it was the second or third query that sounded like a very bad idea. To this day I do not know who asked because the voice came from the back of the group wanting to know what Father was going to do about the football coach.

Maybe a week earlier that question might have seemed timely. After all interim head coach Hugh Devore had just ended the ’63 season with two wins (the final game of the season was postponed in the wake of the assassination) and the years previous were not exactly stellar.

It grew quiet as we waited for the reply. Maybe Hesburgh kept in mind that freshmen could be pretty naive when he said something like this, “There is a time and place for everything and this is not the time—we will get to that issue later.” Which he and (University executive vice-president) Father Edmund P. Joyce, C.S.C., did in early December, hiring Ara Parseghian to turn Notre Dame football around.

All these years later I finally had the opportunity to sit down with Father Hesburgh to talk about the role and importance of sports to the fabric of a great university. With the passage of time it would be easy to forget there was an era when Father Ted was the hands-on administrator who oversaw and overhauled Notre Dame’s athletic department.

In 1949 he was the then-very young (32) executive vice president who reported to Father John Cavanaugh. Father Hesburgh’s areas of expertise were theology and philosophy—and here he was being handed a job he later said he didn’t articularly relish: reorganize the entire athletic department starting at the top.

At the time the “top” equated to Frank Leahy, the greatest football coach (pro or college) in the country. Leahy reported directly to the athletic director, who also happened to be Frank Leahy.

It wasn’t that Leahy was doing anything wrong. It was simply the fact, clearly recognized by Cavanaugh and Hesburgh, that this was a situation ripe for disaster and it was time the entire athletics department, not just the football coach, reported to the University administration.

So what did the 32-year-old theologian and philosopher do? He put in place changes and a system that impacted Notre Dame and many other universities. He had the last say on everything from finances to schedules. He put in new eligibility expectations and requirements that football players and other athletes go to class and reach the same high bar with grades as any other students—and, novel at the time, it would be the team doctor, not a coach, who would decide if an athlete was healthy enough to play. And if an athlete was deemed by the doctor unable to ever play again, he kept his scholarship to Notre Dame. Hesburgh also set the standard for how many players could be on a traveling squad, at a time when there were no restrictions—you could take 11 football players on the road or 111.

These new policies presumably were going to be the big rub between Hesburgh and Leahy—and they might have been one of the reasons that rumors persisted for years that the two could not get along, eventually leading to Leahy’s resignation. All these decades later, Father tells me those rumors were hogwash. In fact, Hesburgh says the first game after the restrictions were put in place turned out to be a bit of a bonding moment between the two.

That game was against the University of Washington in Seattle and it was a game where Leahy was fit to be tied with the officials who seemed to have penalty flags in hand before some plays even began. Hard to believe today, but in his role at the time, Hesburgh watched the game films. He looked at the Washington game and told Leahy that his angst with the officials was quite understandable. And the game in Seattle changed forever how Notre Dame would approach road trips. Hesburgh took the train with the team round trip to Seattle, which meant the players were away from campus for nearly a week. That was going to end right there. Notre Dame, already the longtime leader in coast-to-coast college football, would fly from now on to far-away sites—and it had nothing to do with comfort but everything to do with athletes as students first. Too much time away from the classroom did not translate into academic excellence.

The final step in the rapid reorganization of the athletics department was to put in place an athletic director who reported to the executive vice president in the chain of command. As it turned out, the perfect candidate occupied an office in the basement of Breen-Phillips Hall, head basketball coach Edward “Moose” Krause. But Moose would have to give up his duties as head basketball coach because that was the way it was going to be from now on. He did and the rest is part of Notre Dame lore.

As Hesburgh said in his autobiography, Notre Dame now had a strict system of checks and balances in place for coaches and players. That included any candidate for a coaching job having to sit down with Hesburgh, Joyce and Krause and being asked if they had read the rules and whether they were prepared to follow all of those rules. The very same policy has been followed by Notre Dame athletics directors since, including Jack Swarbrick today. Back then Hesburgh called it an “honest” system and honesty has been the best policy ever since.

When Hesburgh took over as Notre Dame president he turned over the leadership of the athletics department to Joyce—though the buck still stopped at Father Ted’s desk, as it does today with current University president Rev. John I. Jenkins, C.S.C., when necessary.

Hesburgh met with any Irish head coaching candidate. In general, Hesburgh’s message contained three consistent points. One, we think we have the resources at Notre Dame for you to be successful. Two, we expect your athletes to go to class and graduate. And, three, if you break any NCAA rules, you’ll be headed out of town on the next train. In his mind, it was that simple.

After retiring from his position at Notre Dame, the former Notre Dame president served as co-chair of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics, which studied reform in college sports from 1990 to 1996 and again when it reconvened in 2000. Under the leadership of Hesburgh and co-chair William Friday (University of North Carolina president emeritus), the commission advocated for presidential control of intercollegiate athletics, rigorous academic standards for athletes and a certification process requiring athletics departments to prove they were running fiscally responsible, equitable and ethical sports programs. The Knight Commission’s report laid out 20 reform proposals, 10 of which were passed at the January 1992 NCAA Convention.

Truth be told, during his time as Notre Dame president, Hesburgh depended heavily on Joyce to deal with athletic matters day to day—as did his successor, Rev. Edward “Monk” Malloy, C.S.C., with his executive vice president, Rev. Bill Beauchamp, C.S.C. The point remained—any athletics department needed University administrative oversight.

Hesburgh’s approach—and success—met with respect at all levels of college athletics. In 2004 when Myles Brand began the NCAA President’s Gerald R. Ford Award to honor an individual who had provided significant leadership as an advocate for intercollegiate athletics on a continuous basis over the course of his or her career, the award went to Hesburgh. A year later he received the Dick Enberg Award for promoting the interests of student-athletes while advocating for the values of education and academics from the College Sports Information Directors of America (CoSIDA).

Hesburgh does not like playing favorites within the Notre Dame family, but I had to ask, just for the record, if he had any favorites as he looks back on the legends.

He paused, not to demur, but to give it good thought.

For the record, they are John Lattner (1946 Heisman trophy winner) and former head coach Ara Parseghian.

Anything else?

Yes, he said, keep playing Navy every year and consider adding Army and Air Force on the schedule more often. When it comes to trying to do it right, he says, they are the mirror images of Notre Dame.

Hesburgh will always be the heart and soul of Our Lady’s University and nothing capsulizes his love of the place better than a line from his valedictory address as president.

“To have been president of such a company of valiant searching souls, to have shared with you the peace, the mystery, the optimism, the joie de vivre, the ongoing challenge, the every-youthful ebullient vitality, and, most of all, the deep and abiding caring that characterizes this special place and all of its people, young and old, this is a blessing that I hope to carry with me into eternity, when that time comes.”

As I left him this time I asked one final question. Father, given a choice, would you rather win a football national championship or have one of your professors win a Nobel?

He did not demur. He did not pause this time.

“This is Notre Dame. We can win both.”