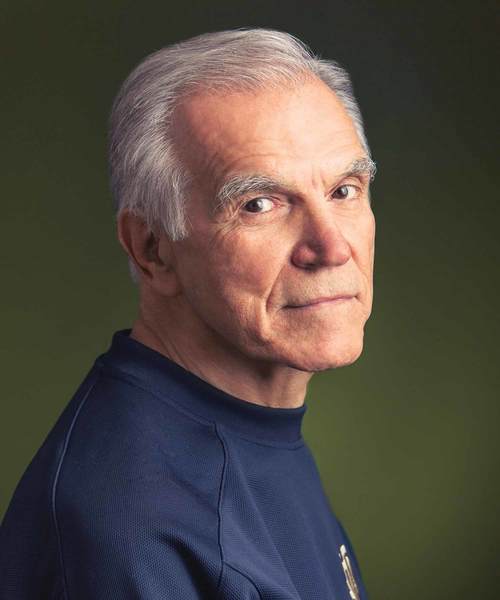

Brian O'Gara

A life-changing event

Without ever recording a strikeout, Brian O’Gara has been an intricate part of the past 26 Major League Baseball All-Star Games.

A member of the University of Notre Dame graduating class of 1989, he has never gotten a base hit, yet he has worked at 136 World Series contests. He has never managed a big-league club, yet every autumn for the past 22 years, after the final out of the World Series, O’Gara has hoisted the Commissioner’s Trophy.

O’Gara is Major League Baseball’s vice president for special events. Fields of dreams are his office. The Midsummer Classic and the Fall Classic are to him what Christmas is to Santa Claus. At baseball’s gem events he oversees the pre-game ceremony, in-park entertainment and the trophy presentations. Anything of entertainment value outside the realm of the players and umpires is O’Gara’s domain.

“We never forget that the game takes center stage,” says O’Gara, 49, “but we are building life moments and memories for people.”

The gig puts O’Gara in the midst of some unforgettable moments and company. At the 2009 All-Star Game he found himself making small talk with President Barack Obama before he threw out the first pitch (“I was so comfortable that I said, ‘Nice jacket’ in the way you’d tease a buddy,” says O’Gara, referring the POTUS’s Chicago White Sox jacket). At the 2013 All-Star Game he oversaw the sound check for Neil Diamond as he rehearsed “Sweet Caroline” at Citi Field. At the 2016 World Series he toted the World Series trophy from its secure and undisclosed location in the bowels of Progressive Field to the waiting arms of commissioner Rob Manfred, who presented it to the Chicago Cubs after a 108-year wait.

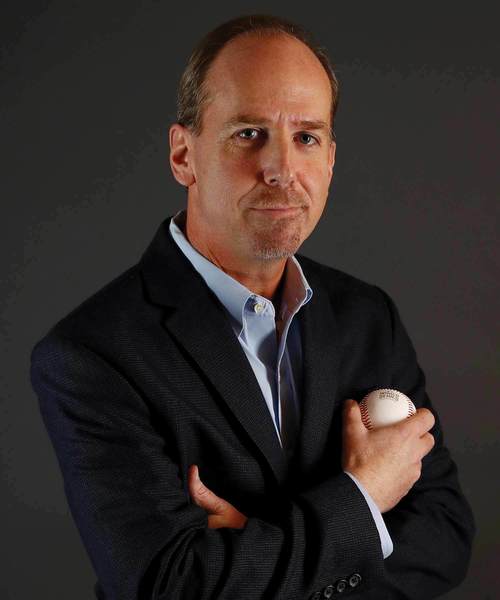

“A batter has to keep his eye on the ball, but Brian has to keep his eyes on a number of balls at once,” says his longtime friend and colleague, Joe Garagiola Jr., a 1972 Notre Dame graduate. “There’s a minute-by-minute itinerary in the hour before an All-Star Game or a World Series game, and Brian’s job is to oversee all of it. He’s like an umpire—when it all goes seamlessly, you don’t even notice he’s doing his job so well.”

The Westbrook, Maine, native is the ideal man for the job. As a Little Leaguer in 1979, he played third base on a state championship team. As a recent Notre Dame grad in 1989, O’Gara and a classmate took a circuitous route from South Bend to his New England home by visiting every Major League ballpark along the way (and a few that were out of the way). As a dad he made an annual pilgrimage to the Little League World Series in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, with his son, Sean.

“Most people’s homes have a bowl of fruit on the dining room table,” says Sean, 19, the oldest of O’Gara’s three children (daughters Megan and Molly are in high school). “Ours has a bowl of baseballs from different World Series games.”

Seated in his Park Avenue office, O’Gara procures a worn baseball ticket from a Milwaukee Brewers-Boston Red Sox game. The date: September 14, 1975. The price: $3.75. The location: Section 10, Row 15, Seat 8.

“My first baseball game,” says O’Gara, whose parents would pile him and his three siblings into the family’s lime-green station wagon for an annual pilgrimage to Fenway Park.

“Hank Aaron was back in Milwaukee that season (he’d spent his first 12 seasons with the Milwaukee Braves) and he hit his 745th home run.”

Twenty-four years later, in 1999, O’Gara had the sublime and surreal task of directing the pre-game ceremony at the All-Star Game at Fenway Park, the introduction of the living members of baseball’s All-Century team. It was his duty to coordinate a ceremony including the game’s greatest living legends, including Red Sox immortal Ted Williams and Aaron. At some point he asked Hammerin’ Hank to sign that ticket that he still possessed because, well, Brian O’Gara is someone who cherishes moments and opportunities and people. He touches every base.

O’Gara commutes daily from Fairfield, Connecticut, to Major League Baseball’s Park Avenue offices. Everyone reads on the Metro North railroad, but O’Gara decided to give himself a project for the 80-minute, one-way commute. What is as American as baseball? The presidency.

“I decided I was going to read a biography on every United States president, in order,” says O’Gara.

Like a perfect game or a 56-game hitting streak, O’Gara’s epic quest seemed daunting and, though undertaken with the greatest of ardor, predestined to fail. “Washington: A Biography,” by Noemie Emery would hold anyone’s interest, but what about those middle-innings commanders-in-chief, a John Tyler or Millard Fillmore, how would he endure those tomes?

“There were times I was tempted to quit,” says O’Gara, who completed the odyssey in two years, “but I thought, If I leave James K. Polk for a mystery novel, I’ll never get to Zachary Taylor.”

“I’m so impressed by that,” says Garagiola, baseball’s senior vice president for standards and on-field operations. “Brian said to himself, ‘This is an area of American life and I’m going to know it.’”

O’Gara, a self-confessed “presidential dork,” has met every living U.S. president. Each year he mails All-Star ballots to them and other emissaries. Because, well, why not?

“I once sent a ballot to a secretary of defense whom I had met,” says O’Gara. “He wrote back to thank me and included the line: ‘such diversions must take a back seat.’ That was a blunt reminder of our relative spheres of importance.”

While he loved playing baseball and followed the Red Sox as a kid, O’Gara never dreamt of a career in the national pastime. As a child he wrote and published a weekly newspaper whose sole subscribers were also its subjects: his parents, two older brothers and younger sister.

“It was called The O’Gara Gazette,” says O’Gara, “and some weeks it was more well received than others.”

At Notre Dame O’Gara expanded his readership as a reporter and later a sports columnist for The Observer. He vividly recalls interviewing former football coach Lou Holtz following a Bookstore Basketball game in which Holtz had taken part.

“He gave me a great quote about how it felt like he was on a flight where he should have gotten off in Denver,” says O’Gara, “but continued on to Los Angeles. He was a little worn out.”

During his senior year O’Gara was assigned a story on the athletic department’s initiative to improve its prowess in Olympic sports. One of his interview subjects was then associate athletic director Bubba Cunningham, who was duly impressed with O’Gara and encouraged him to apply for a postgraduate internship in the Notre Dame athletic department. That internship led to a subsequent internship with Major League Baseball.

“From the beginning Brian was just a great person to be around and a great person to work with,” says Cunningham, now the athletic director at the University of North Carolina. “I saw how bright he was. His success doesn’t surprise me in the least.”

Interns do not start out on third base, in or out of baseball.

“I tried to learn and do as much as I could,” says O’Gara, who began his internship in Major League Baseball in the spring of 1990. “I finally landed an entry-level job as a special events administrator, which involved a lot of hotel arrangements and securing conference rooms for meetings.”

By 1999 O’Gara was overseeing in-game activities at the All-Star Game and World Series. His inaugural event was the aforementioned Midsummer Classic at Fenway.

“That is still the worst rehearsal I’ve ever been a part of,” says O’Gara, whose job it was to corral two dozen of the game’s greatest living legends along with Kevin Costner, the ceremony’s narrator.

“We had technical glitches and timing issues. I remember Costner calling Joe Morgan’s name and flapping his left arm (a batting tic the Hall of Fame second baseman had) and no one else seemed to get the joke.”

O’Gara understood that, as the skipper of the event, he must maintain an even keel. More Joe Torre than Billy Martin. It worked. The event was not only seamless and magical (you may recall the sight of the All-Stars gathering around a wheelchair-bound Ted Williams in front of the pitcher’s mound), but after the game O’Gara received a message: Teddy Ballgame was inviting him and his family to meet him the next morning in his hotel room so that Williams could thank him.

“I had a favorite uncle who had met Williams once and always told us the story,” says O’Gara. “He’d say in a thunderous voice, ‘And in walks Theodore Samuel Williams!’ So you can imagine what it was like for me to meet him and introduce my kids to him. It was a dream come true.”

Baseball is timeless. There is no clock, of course, and the paths between each base have remained 90 feet apart across three centuries. The game is evergreen; people are not. In 2015 O’Gara first lost his mother in May and then his father around Christmas due to unrelated illnesses. In the interim he began suffering bouts of nausea, dizziness and fatigue.

“I’m not a runner, but on New Year’s Day 2015 I had challenged myself that I would run a half-marathon,” says O’Gara. “And I did that March. I was in the best shape in years. Less than six months later I got the diagnosis. I went from a peak to a valley.”

The diagnosis was throat cancer. On Feb. 16, 2016, his 49th birthday, O’Gara underwent his first chemotherapy treatment at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in Manhattan. He had already been enduring daily radiation treatments while continuing to work. Few of his co-workers knew why he was ducking out of the office each day.

“When my dad sat my sisters and me down to tell us,” says Sean, “the first thing he did was tell us that the cancer was not genetic. His first thought was to ease our minds.”

The most noticeable change in O’Gara’s regimen was his choice of seat on the train.

“I had to make sure I was seated next to the bathroom,” he says, “because I couldn’t make it through a commute without throwing up.”

Meanwhile, baseball cared. Sandy Alderson, the general manager of the New York Mets, gave O’Gara the keys to his apartment located close to Memorial Sloan Kettering for those days when he was too wiped out to commute home. Red Sox slugger David Ortiz left a get-well voice message. His family, too, was an absolute anchor.

“My daughter Megan has battled terrible migraine headaches through middle school and high school,” O’Gara says. “Seeing how she has always handled that with quiet courage fortified me.”

He also drew strength from his alma mater.

“In the toughest moments, your mind wanders to look at places that meant something to you,” O’Gara says. “I don’t want to get all Tom Dooley on you, but I made up my mind that I wanted to get back to the Grotto.”

After undergoing chemotherapy and radiation treatments in the winter and spring, O’Gara felt well enough to work the 2016 All-Star Game in San Diego. In 2009 Major League Baseball had begun working with the charitable foundation Stand Up To Cancer at its All-Star Games, a program that O’Gara had helped bring to fruition. At every game after the fifth inning players and fans alike are invited to hold up a card that reads “I Stand Up For” followed by a name that each person writes in.

For obvious reasons, O’Gara was anxious about the 2016 installment of this budding tradition. But he still had a job to do.

“I’m in the control booth at Petco Park and Rachel Platten is performing ‘Fight Song’ right in front of home plate,” he says. “Fox television is broadcasting this live, so we want to get this right.”

As O’Gara focused on the sound quality and other details that the home viewer would never notice unless an error was committed, someone tapped him on the shoulder. O’Gara turned and the person pointed to the outfield, where the giant video screen was playing Fox’s feed. There stood Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred, holding two signs. One of them read, “I Stand Up For Brian O’Gara.”

“I definitely felt a lot of eyeballs on me at that moment,” O’Gara says.

In September doctors told O’Gara that all traces of his cancer had vanished. He will need to go in for cancer screenings regularly, but last autumn he was thrilled to be back to work and cancer-free.

“I have never seen anything like what I witnessed at Wrigley Field on the Friday afternoon (before Game 3 of the World Series, in Chicago),” he said days after the Cubs had clinched the championship.

“Five hours before the game, and there had to be 15,000 people just hanging around the streets surrounding the ballpark. They were taking pictures, soaking in the atmosphere, just so happy to be finally able to touch and feel and experience the World Series.”

It was a joyous celebration that O’Gara himself understood and appreciated. He had always cherished such moments, but now even more deeply.

“Everyone will get back to their daily lives soon enough,” he says, “but right now Cloud 9 is pretty crowded.”