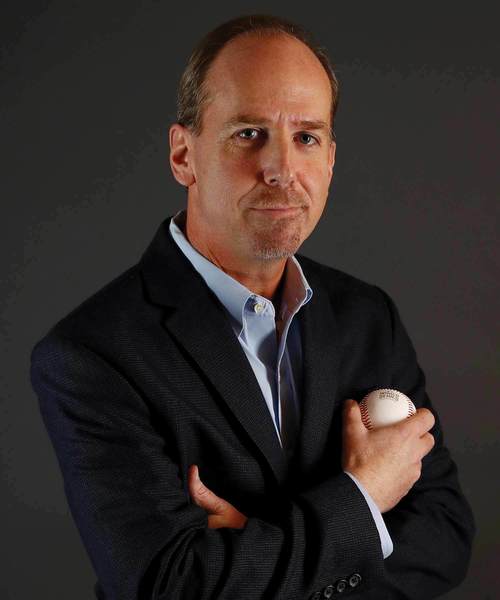

Dr. Angelo Capozzi

Putting smiles on lots of faces

A mother will tell you that the moment she first holds her child and welcomes that new little life into the world is nothing short of miraculous. For too many mothers, however, particularly in underdeveloped nations, that moment is marred by fear and anxiety when a child is born with a cleft lip or palate.

According to recent Centers for Disease Control estimates, each year in the United States about 2,650 babies are born with a cleft palate and 4,440 babies are born with a cleft lip with or without a cleft palate. Very few of these cases remain untreated—health care providers and the public health system routinely subsidize the cost of reconstructive surgery for American children born with cleft lips or palates.

There are, however, approximately 235,000 children born each year worldwide with cleft lip and palate deformities. Most of these children are in poor, developing countries where access to qualified medical personnel and equipment is limited or non-existent. In addition to difficulties with feeding and talking, those with untreated clefts often face terrible social stigma, including being rejected from society and deprived of an education.

Dr. Angelo Capozzi has made it his goal to eliminate untreated lip and palate defects, worldwide. Having completed more than 60 medical mission trips spanning nearly four decades, he’s well on his way.

Capozzi is the medical director and co-founder of Rotaplast International, a nonprofit humanitarian organization with a vision for worldwide community service. Since its inception in 1992, more than 190 Rotaplast missions in two dozen of the world’s poorest nations have brightened the smiles and the future for children born with cleft lips and palates. Corporate and individual donations have enabled Rotaplast medical teams to perform reconstructive surgeries for more than 17,000 children. Rotaplast also educates families and communities toward mitigating the stigma of cleft defects.

Cleft lips and cleft palates occur when the cells that comprise facial tissue do not completely fuse before birth. In normal fetal development, the lip forms as early as the fourth week of pregnancy and the roof of the mouth is formed by the ninth week. While doctors do not fully understand what causes cleft defects, evidence suggests that genetic predisposition; environmental factors including pollution, poor nutrition, alcohol and nicotine use; maternal diabetes; and certain medicines taken to treat epilepsy are among possible factors.

Depending on the severity and location of a cleft, routine ultrasound is effective for in utero diagnosis. Corrective surgery usually is recommended within the first few months after birth, not only to improve the appearance of the child’s face, but also to allow for proper breathing, hearing, speech and language development. Often, children who are born with a cleft anomaly require additional services or surgeries, including speech pathology and orthodontia, well into their adolescent years. The American Cleft Palate Association estimates the lifetime cost for care of one individual with a cleft lip or palate at more than $100,000.

The process of coping with and overcoming a cleft lip or cleft palate is neither quick nor easy. By the same token, exaggerating the significance of Capozzi’s mission and ministry is hardly possible.

Even after performing thousands of operations, Capozzi still encounters a deep sense of awe whenever he completes a surgical procedure. In a 2012 article for The Golden Domer, a newsletter for senior alumni of Notre Dame, Capozzi wrote, “After repairing a child’s cleft lip and palate and you put the last stitch in, you get to stand back and look at the results and say, ‘Wow, I made a difference for that kid.’ I’ll tell you, there’s no reward like that.”

That profound sensation on his first mission in 1976 is what initially propelled him to devote his practice to humanitarian medicine.

He relates how the chief plastic surgeon from Stanford University invited him on a quick trip to Mexicali, Mexico, with an organization named Interplast (now known as ReSurge). The two doctors set up a makeshift clinic in the basement of a house and then spent three days performing round-the-clock surgeries in a dilapidated rural hospital. Most of the operations were on children with cleft deformities. Capozzi knew from this time that medical missions would be part of his professional life for the rest of his life.

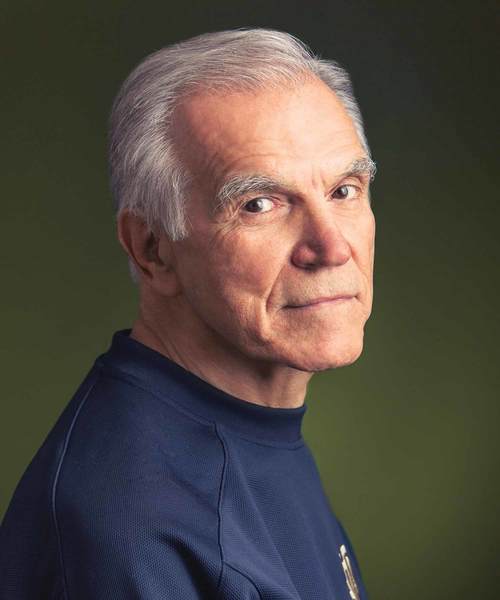

Notre Dame vice president and athletics director Jack Swarbrick often points out the difference between transaction and transformation with respect to service-leadership. Anyone can perform an act of charity—and, while donating money to a cause is, of course, laudable, the potential for transformation is rarely present without true self-sacrifice.

“It’s different than just writing a check, when you experience a Rotaplast mission,” Capozzi says. “The poor unfortunate mothers and fathers bringing their deformed children to you for help, for hope. To make them whole and give them a future makes an unforgettable, lasting impression. The desperate parents trust us, strangers, with their children. Never will you find more grateful people. That is when I realized that touching someone’s life gives you the greatest feeling there is.”

Such is the power of transformation—not only for the children whose lives he touches but also for others who volunteer with Rotaplast—and Capozzi has discovered firsthand that in giving away one’s whole self, the return is exponentially greater than the investment.

Capozzi grew up near Syracuse, New York, in a small town called Mattydale (which, incidentally, also is home to former Notre Dame president Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C.). He tells how, as a youngster in the 1940s, he used to move a kitchen chair next to the refrigerator so he could listen to Notre Dame football games on the radio. As one of five children born into a working-class family, he never imagined he’d have the opportunity to attend college.

“Turning onto Notre Dame Avenue and seeing the Golden Dome for the very first time was akin to being struck by lightning,” Capozzi says, without a hint of shame about such hyperbole. “That was back before the Dome was hidden by all those trees—you could see it in all its glory—but trees are important, too, so it’s okay,” he says with a chuckle.

He came to Notre Dame in 1952 on a baseball scholarship under legendary Irish coach Jake Kline. Left-handed pitcher Capozzi had a mean fastball but was thought unlikely to achieve academic success as a pre-med major.

“My adviser told me to stay away from anything having to do with a focus in science,” he says. Brimming with cheek, Capozzi replied that he already knew he was going to be a doctor. He thanked the adviser, ignored the advice, stepped up to the plate and graduated with honors in 1956.

From there he attended the Stritch School of Medicine at Loyola University in Chicago, completing general surgery training at St. Francis Hospital in Evanston, Illinois, and a plastic surgery specialty at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

In 1964 Capozzi and his wife, Louise, moved their two young sons (Angelo and Leonard) to Fairfield, California, where he was stationed as a surgeon in the Air Force. Because Travis Air Force Base served such a large geographical area, Capozzi was allowed to have a civilian assistant. The subsequent relationship with Dr. Vincent Pennisi launched Capozzi’s career and 22 years of professional and familial symbiosis before Pennisi’s passing in 1994.

At the urging of some of his colleagues, Capozzi joined the Rotary Club of San Francisco in 1971. After hearing about his trip to Mexico in 1976, the club began sponsoring additional medical mission trips with donations of $5,000, supporting the work of Capozzi and Interplast for 14 years.

In 1992, the president of San Francisco Rotary, attorney Peter Legarias, approached Capozzi about the possibility of a medical mission to Chile. Legarias and his wife had adopted a baby girl from that country and wanted to express gratitude in some significant capacity through making a positive impact in their daughter’s homeland.

Thrilled at the opportunity, Capozzi, a nurse and a non-medical Rotary colleague met with Rotarians in Chile to discuss logistics and determine a suitable location. Conceptually this was quite different from Interplast missions, which were exclusive to licensed medical personnel. The first Rotaplast mission took place in La Serena, Chile, in January 1993.

Thirty-one people, including surgeons and Rotarians, made that inaugural mission to Chile. Capozzi says, “The Rotarians, in particular, came back all excited by the life-changing experience and they couldn’t wait to get involved again and to get even more people involved. We just kept doing missions and the word kept spreading through the Rotary world. We never expected this kind of success or future.

“Lots of people have contributed to nurturing and developing my organization. I cannot do this by myself. Success like this depends on other people and a shared passion. I am grateful for my children, Angelo, Len and Jeanne. My wife, Louise, in particular, has always been wonderfully supportive, especially when the kids were young. She has gone with me on many missions since Rotaplast started and also tolerated my wandering around the world with great acceptance and understanding.”

In recognition of Capozzi’s extraordinary contributions and the impact he has had on countless children worldwide, the Notre Dame Monogram Club bestowed upon him its highest honor earlier this year.

Monogram Club executive director Brant Ust notes, “Dr. Capozzi has continued to exemplify the core values of the University through his worldwide service and dedication to others in the most humble and sincere practices of healing and medicine. We are proud to have Dr. Capozzi represent the impact that members of the Monogram Club can have through these lifelong commitments after Notre Dame. It is only fitting that he is also a recipient of the Moose Krause Distinguished Service Award.”

This was not the first significant University honor for Capozzi. In 2001, he received the Dr. Thomas A. Dooley Award from the Notre Dame Alumni Association, conferred to an alumnus/alumna who has exhibited outstanding service to humankind. He was the 1997 recipient of the Bay Area Alumni Association Exemplar Award and in 1985 was recognized as the Bay Area Alumni Association Man of the Year.

In sharing his life and his talents, Dr. Angelo Capozzi arguably has put smiles on the faces of more people worldwide than any other Notre Dame alumnus in history.