Bryant Young

His Son, His Superhero

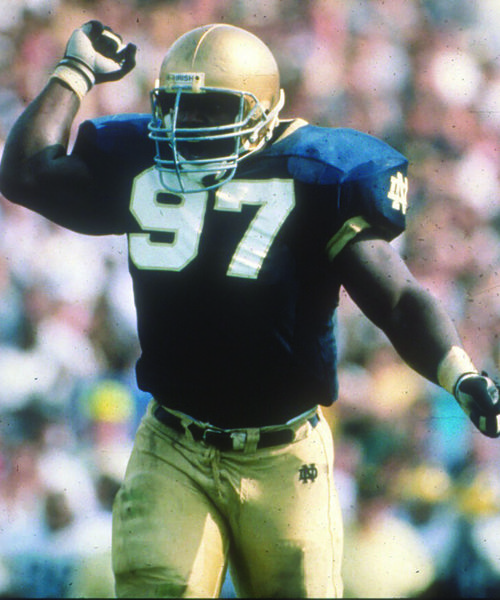

Bryant Young played defensive tackle for Notre Dame from 1990 to 1993, serving as an Irish team captain in 1993 and earning first-team All-America hon ors that season. He went on to play 14 seasons for the NFL San Francisco 49ers, four times earning All-Pro recognition. This story originally appeared on ESPN. com on Oct. 11, 2017, and is reprinted by permission of ESPN.

Atlanta Falcons defensive line coach Bryant Young often thinks about the joyful times he had with his son Colby, a kid who had a passion for football and a knack for cooking.

He also remembers the sadness that overwhelmed him when he uttered his last words to his teenage superhero.

“I told him just how much I appreciated his courage and his resilience,” Young said as his voice cracked. “And I told him I love him. I told him how much I was proud of him, for the young man to go through something like that.”

Bryant Colby Young died of pediatric cancer at age 15 on Oct. 11, 2016. Bryant Young knew every day without his son would be difficult, but especially days such as Colbyʼs birthday on Aug. 19 and the anniversary of Colbyʼs death.

“Every day has its own challenge,” Young said, “but when youʼre going through the first of everything — the first birthday, the first year of him passing — and actually the day before, too, just anticipating what the day would be like. I definitely always want to remember him in a special way.”

Colby was known as a delightful, vibrant young man. His family never imagined a day of throbbing pain would result in sorrow for years to come.

It was 2014, and Colby was an eighth- grader playing football in Charlotte, North Carolina. He came home one day complaining of a headache.

Young, a Hall of Fame nominee who played 14 seasons on the San Francisco 49ersʼ defensive line, figured he knew what the issue was with his son.

“I thought he got dinged,” Young said. “But he was like, ʼNo, Dad, I didnʼt get dinged.ʼ”

Young saw that something was off when Colby woke up on a Wednesday morning in excruciating pain with no desire to eat. There was a middle school retreat the same day, one Colby eagerly packed for the night before, but the pain drained him of his enthusiasm. He couldnʼt sit up at the dining room table, so Youngʼs wife, Kristin, took Colby to the pediatrician.

“The doctor looked at him and thought at the time, he was 13 and was going through puberty, and thatʼs pretty common for a kid that age to possibly have migraines, as growing pains,” Young said. “So she prescribed him medication for migraines.”

The pain never subsided throughout the remainder of the day. Colby began to vomit. The pain intensified by the next morning.

“He was bald at the time, but he was trying to pull his hair out of his head, so we knew it was something more serious,” Young said.

The Youngs returned to the pediatrician. The prescription for the migraine changed. But before leaving this time, Colby underwent a CAT scan, which finally revealed the cause of his painful episodes: a mass on his brain.

“Hearing the news, he was scared. My wife was scared,” Young said. “They diagnosed it as a pineal tumor. It was about the size of a golf ball in his pineal gland region [vertebrae brain].”

Colby needed surgery. The surgeon performing it had completed the “risky” procedure in the past.

“He felt pretty confident that with what he had seen before and had removed that it was going to be OK because it wasnʼt growing out and was contained,” Young said. “He said he wouldnʼt know if it was non-cancerous until sampling the tissue and removing it. We thought we caught it.”

The surgery dragged on for four hours, which seemed like an eternity. Bryant and Kristin continued to cling to the doctorʼs words about it being an “operable” process. Then the surgeon emerged bearing news.

“Just the look on his face, I didnʼt like it,” Young said. “I just had this eerie feeling about it being bad news. So he gets us into a conference room and tells us that it was cancerous. It was an even bigger blow just to hear that.” There were never any signs of Colby being sick while growing up. He played football and basketball without issue.

After the surgery, which occurred on a Tuesday, Colby was back in school Wednesday of the following week. But he still had to endure chemotherapy once he recovered from the surgery.

“Just what radiation and chemo do to you, it wrecks the body and makes you feel a certain way, and it was just hard seeing him go through that,” Young said. “But throughout the whole process, he was strong. He had great support around him.

“You hear about others going through stuff like that, and you support others that are going through it. But itʼs a tough deal when youʼre in the fire yourself.”

Young admired Colbyʼs spirit during the bout with cancer and how determined he was to live life to the fullest. But during treatments at the MGH Francis H. Burr Proton Beam Therapy Center in Boston, Colby received more bad news.

“He was emotional when he heard about cancer,” Young said, “but I think even it hurt him, even more, when the doctor told him, ʼBecause of the radiation, the muscles in your neck will atrophy, and we highly recommend that you donʼt play football anymore.ʼ That crushed him."

Colby was a cover corner in football and also played outside linebacker. Now he could be only a spectator as he went through radiation treatment from October to the beginning of December 2014.

“He was mature in a way that it hurt him, and it was a blow to his spirit, but he didnʼt let that keep him down,” Young said. “So then he really focused on basketball once he went through radiation and recovered from that.”

Colby started chemotherapy at Duke University in January 2015. It was a four-month process. He relapsed, so the Youngs found a clinical trial at the University of Florida Shands Hospital that entailed immunotherapy, a process that involves using the individualʼs immune system to try to fight cancer.

It wasnʼt enough to help Colby recover, though the family remained hopeful throughout the various forms of treatment. Kristin documented her sonʼs grueling journey through her blog, chronicling how Colbyʼs cancer grew and how the Christian-based family relied on Godʼs will.

The Youngsʼ other five children — three daughters and two sons — came up with T-shirts to support their ill brother, bearing a Superman-themed logo with a large “C” in the middle to represent Colby. Some of Youngʼs former San Francisco teammates wore the shirts to a 49ers-Buccaneers game in October during the NFLʼs breast cancer awareness month.

Young was grateful to have support from the entire 49ers organization and former team owner and NFL Hall of Famer Ed DeBartolo.

“Bryant is a one-of-a-kind man with a wonderful and caring family,” DeBartolo said. “They suffered so much with Colby all those years but never, ever wavered. I believe if youʼre lucky enough to be blessed with the ability to help, you have to do whatever you can. I would do anything for Bryant, Kristin or his family — like a younger brother.”

The Youngs always emphasized to their children how important it is to give rather than receive. Colby took the message to heart with his “Change for Change” campaign. He wanted to collect $2,000 to donate to the Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation by placing change buckets around his town. Colby raised more than $50,000 thanks in large part to the help of his high school, Charlotte Christian.

“He was going through it, and he came up with the idea of how he can bring awareness and have people be a part of something that affects so many kids and families,” Young said. “It was incredible in terms of what he did.”

The Youngs also had a short documentary produced by a friend that captured some of Colbyʼs fight as well as his living life to the fullest, including preparing meals such as steak and chicken stir-fry for the family.

“Little did we know that we would use that video at his service, not knowing how things were going to turn out,” Young said. “Part of what compelled us to share that was our story is not to be our own. We need to share that and allow people to understand the pains while sharing our faith through the process.

“It was therapy for us, too, as a family, to be able to tell our story. To do that in the way we did it, I think, was a blessing for us and hopefully for others.”

After spending most of the last four months of his life in hospice care, Colby died at home on Oct. 11, 2016.

“I tried to prepare emotionally for his moment of death, but there really is nothing that can prepare you for it,” Kristin said. “Mixed in with the deep waves of grief and sadness on the day he passed away was also insurmountable joy and peace that his sweet soul was free again in heaven.”

Before every game, Young quizzes his defensive linemen on a variety of topics related to that weekʼs opponent. Fifteen questions, to be exact.

The players werenʼt aware, but there is a reason Young came up with that number.

“Colby was 15 when he passed, so thatʼs my way of just kind of intertwining him in all of that,” Young said. “Colby loved football so much that heʼs a part of what I do with my job. He would be the biggest cheerleader of what weʼre doing here.”

Falcons coach Dan Quinn was the defensive line coach in San Francisco in 2003-04, when Young played for the team. Quinn remembers when a 2- or 3-year-old Colby would walk around with a No. 97 49ers jersey that read “My Dad” on the back.

Quinn understands the pain the Youngs are going through still today.

“I donʼt know if I helped them, but just being there,” Quinn said. “We want to be up there to let Kristin and B.Y. know that, ʼHey, man, this is as tough as it gets. And weʼll stand by you, stand next to you.ʼ There are no words of encouragement to give during those moments. Itʼs just, ʼI love you, man,ʼ and support.”

Young stepped away from coaching in 2013, the year before Colbyʼs cancer surfaced. He was the defensive line coach at Florida — brought there when Quinn was the Gatorsʼ defensive coordinator — and at that time, he wanted to focus more on his family. Colbyʼs health then became the top priority.

Young had a coaching internship with the Falcons two seasons ago. Then he replaced Bryan Cox as the defensive line coach in February, following the Falconsʼ Super Bowl appearance. Returning to full-time coaching after his sonʼs death wasnʼt a difficult decision.

“It was time,” Young said. “I wanted to get back. I kind of missed it in that way. We had been through so much. Time allowed that to happen. As things settled down, we took time to heal. And weʼll continue to heal. I think football has been a distraction in a lot of ways to help me continue to move forward and live life.”

One Sunday game against the Dolphins has been designated as the Falconsʼ “Crucial Catch: Intercept Cancer” campaign game, part of the NFLʼs initiative to bring more awareness to the fight against all cancers — not just breast cancer, which was its previous focus.

There is no doubt that Young's mind will be on Colby and the courageous, two-year battle fought by his son.

“It put things in perspective,” said Young, who plans to wear something special on Sunday to honor his son. “We think itʼs hard out here. We strain, and we grind, physically, to live another day. But to see firsthand and experience somebodyʼs tough battle through a disease, it lets you know life is precious.

“This is just football.”