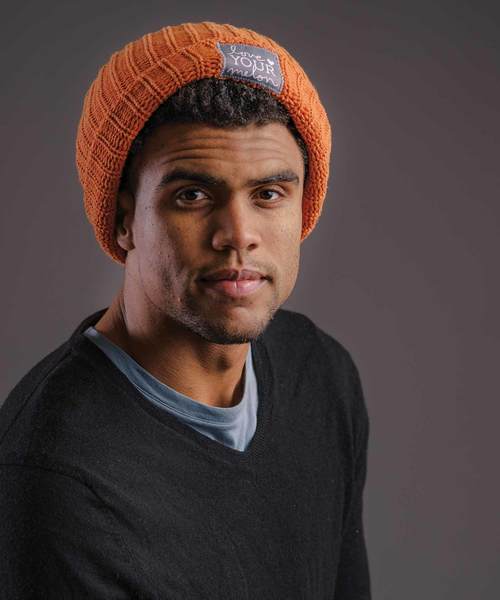

Corey Robinson

Leading from all corners

The progression from student-athlete to student leader at the University of Notre Dame came as naturally to Corey Robinson as running a deep out route, even if the circumstances that helped inspire the move were not ideal.

Robinson had emerged as a potent weapon for the Irish football team, a wide receiver with speed, strength and sure hands to complement his 6-foot-5 frame. He had 65 catches for 896 yards and seven touchdowns over three varsity seasons.

But tall receivers often leave themselves vulnerable to devastating hits in the performance of their duties, particularly when their routes take them into traffic in the middle of the field. Robinson lost playing time to concussions in his sophomore and junior years and sustained another one in spring practice before his senior season. Always a thoughtful young man, Robinson was aware of the potential long-term effects of head trauma and found himself weighing the thrill of competing at the premier collegiate level against the threat of future impairment. He chose to give up football, announcing his retirement in June of 2016.

“It was an agonizing decision,” he says.

“I loved the game, I loved this team, I love this University. I loved the whole Notre Dame football experience. But I had to think in terms of what was best for my future.”

Robinson had willingly made the commitment necessary for success as an Irish player, but he never let football define him as a person. In that he is not unlike his father, basketball Hall of Famer David Robinson, whose track record for social engagement through philanthropy matches his monumental accomplishments on the court.

“Toward the end of my freshman year I felt like all I’d done was play football and go to school,” Corey says. “I wanted more from my college experience than that.”

He had his father’s example in mind when he and a group of fellow Irish athletes started One Shirt One Body.

It began with a discussion over how best to utilize clothing and equipment they were no longer wearing, and it quickly became a project designed to put used sports gear into the hands of youngsters from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Starting with the distribution of 300 shirts to the South Bend Center for the Homeless, the idea mushroomed into an NCAA-sanctioned, nationwide movement that saw more than 3,000 shirts distributed in the first few weeks it was up and running.

“Just as One Shirt One Body went from an idea to a national initiative, I hope to inspire my fellow students at Notre Dame to become agents of change,” Robinson wrote in a first-person story for SI.com. “Life isn’t about making a living; it’s how you live.”

One Shirt One Body was only the beginning of Robinson’s entrepreneurial activism. He joined the Student Athletes Advisory Committee and eventually became vice president of the nationwide group that works with the NCAA to address issues involving student-athletes in all varsity sports at all collegiate levels. He served as athlete representative to the cabinet of student body president Lauren Vidal and vice president Matthew Devine, who were elected Notre Dame student government leaders in 2015.

In the second semester of his junior year, Robinson decided to run for student body president himself. He and vice presidential running mate Becca Blais were elected in February and took office April 1. Robinson is believed to be the first Notre Dame football player and second African-American student to serve as student body president, following David Krashna, a 1970 graduate and now an Alameda County Superior Court Judge in Oakland, California, and co-author of “Black Domers,” an acclaimed collection of essays recounting the campus experiences of 70 African-American Notre Dame graduates.

Citing One Shirt One Body as a prototype, the Robinson-Blais administration intends to promote social justice through campus entrepreneurship, and it believes it can succeed because “at Notre Dame, you’re surrounded by world-changers,” Robinson says.

“People usually associate entrepreneurship with making money, which is fine, but at Notre Dame we’re focused on service and the idea of making a difference in your community.”

Robinson and Blais intend to raise awareness of sexual misconduct as a campus issue, focusing on prevention but also advocating more timely and humane treatment of victims. They were especially looking forward to sponsoring Racial Awareness Week, with lectures, presentations and panel discussions designed to promote a wide-ranging examination of racial issues and how they’re addressed not only on the Notre Dame campus but across the nation.

“I don’t know that anything like that has ever been attempted at Notre Dame,” Robinson says. “We want to get a conversation started, think in terms of diversity of thought, diversity of experience, diversity of culture. Not just diversity of skin color.”

It’s a full life for a 21-year-old Program of Liberal Studies major, a Dean’s List student who expects to graduate in May with a double minor in business economics and sustainability. But there’s more. Robinson accepted Brian Kelly’s offer to join the Irish coaching staff as a student assistant, working with a wide receiver corps that lost Chris Brown, Will Fuller and Amir Carlisle to the NFL, leaving Torii Hunter Jr., his close friend and fellow Texan, as Notre Dame’s only experienced wide-out.

“This is still my team, and I still want to be part of it,” Robinson says.

He’s a ubiquitous presence on the Irish sideline at games and practices, “coaching up” youngsters Equanimeous St. Brown, C.J. Sanders, Kevin Stepherson, Miles Boykin and Corey Holmes.

“When I was a freshman, Tommy Rees and the older guys went out of their way to help me, to make sure I was getting things and talk me up if I was struggling,” Robinson says. “That’s how it is at Notre Dame.”

Robinson acknowledged feeling queasy from a flashback when Hunter had to be helped from the field after being leveled by a vicious head shot in the season opener at Texas. Hunter was diagnosed with a concussion and missed the Nevada game, but was back for Michigan State in week three.

“Of course I felt for him,” Robinson says. “He’s not only my friend and my teammate, but I know how much work he put in to get ready for his senior year. You hate to see something like that happen to anybody.”

Corey Robinson grew up the middle son of a father who was not only one of this country’s most accomplished athletes, but also one of its most respected citizens. David Robinson literally grew into a college basketball All-American at the U.S. Naval Academy, sprouting from a gangly 6-foot-7 freshman into an unstoppable 7-foot-1 senior. The Midshipmen compiled a 106-25 record on “the Admiral’s” watch and reached the Elite Eight of the NCAA Championship in 1987 when Robinson was voted national player of the year. A powerful left-handed package of size, strength and agility, David Robinson averaged 21 points, 10.3 rebounds and 4.5 blocks per game over his Navy career.

The epitome of a student-athlete, he was also a Dean’s List academic performer who majored in mathematics. But at 7-1, he was not only the tallest midshipman ever to graduate from the Naval Academy, he was too tall to fly airplanes, to serve on a ship or a submarine or engage in any other warfare specialty as a line officer.

The Navy offered Ensign Robinson a compromise: two years of active duty in lieu of the five he’d committed to upon accepting his appointment to Annapolis, followed by four years of service in the Naval Reserve. With permission from the commanding officer of his unit, the best known reservist in the country would be “free to seek outside employment,” which awaited Robinson after the San Antonio Spurs took him with the first overall pick of the 1988 NBA draft. His basketball legend continued to grow as a pro: Robinson won two NBA titles with the Spurs, plus two Olympic gold medals, the first as the starting center on the 1992 “Dream Team” at the Barcelona Games. His individual accolades included 10 All-Star games, Rookie of the Year (1990), Defensive Player of the Year (1992) and Most Valuable Player (1995).

David Robinson was named one of the NBA’s 50 greatest players in a poll taken in conjunction with the league’s 50th anniversary in 1996. Some children would struggle trying to emerge from such an imposing shadow, but Corey never saw it as a burden.

“I have always been proud to be David Robinson’s son,” he says. “From an early age I was aware of his values, his integrity, how he interacted with people. Why would you not want to be around a man like that? It’s an honor to have David Robinson for a father.”

Indeed, David Robinson’s accomplish-ments away from basketball are legend unto themselves, lest anyone wonder where Corey comes by his commitment to serving others. With Valerie Robinson, his wife and the mother of their three sons—David Jr., 23, Corey, 21, and Justin, 19—he started the David Robinson Foundation, which supports early childhood centers, a variety of educational programs and Christian Fellowship organizations. He has committed more than $9 million of his own money to start and support Carver Academy, a Christian-themed charter school serving the economically disadvantaged east side of San Antonio.

“I didn’t have a lot to do with being 7-1—it was a gift, just as my talent as a basketball player was a gift,” David Robinson has said. “This is my opportunity to give back. God has given me more than I could have hoped for, so it’s my responsibility to give back.”

Why would you not want to be around a man like that? Corey Robinson grew up believing he would follow his father to the Naval Academy, but a recruiting trip to Notre Dame changed everything.

“To realize you were walking the campus that Knute Rockne walked, playing on the field where Tim Brown and Rocket Ismail played … what an incredible feeling” Corey says. “I just knew that this was the place for me.”

The feeling intensified every time he ran through the tunnel and onto the field at Notre Dame Stadium as a player, and it hasn’t diminished now that he’s making that exhilarating trip as a coach.

“It’s different,” he says, “but it’s still incredible. You know you’re part of something that’s really special.”