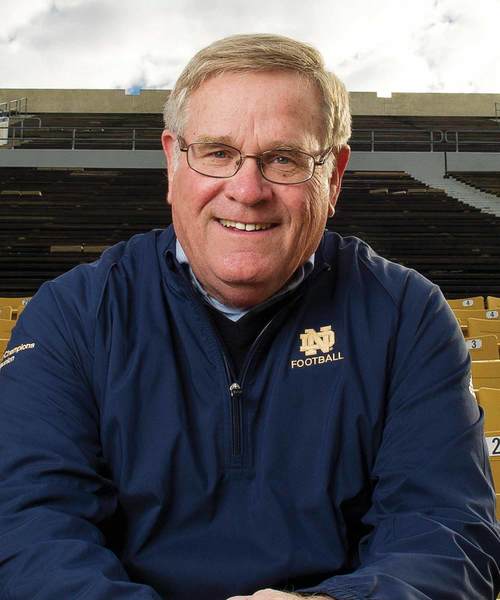

Dan Harshman

He made a career of giving back

The first time Dan Harshman worked with young people with disabilities, it didn’t go so well. It was 1966, his senior year at the University of Notre Dame, and his roommate had taken him to volunteer at the Northern Indiana State Hospital, then located near campus on Notre Dame Avenue.

“That wasn’t a slam-bang experience,” Harshman says. “These were some of the most severely handicapped kids in the state. Many couldn’t talk, walk or take care of themselves. They needed a lot of care. It knocked my socks off to first go there as a college student.”

If you had told him at the time that he’d just found his life’s calling, he never would have believed you. But years later he would return to almost exactly the same address to lead a different organization as a champion for the rights, health and well-being of people with developmental and physical disabilities. When Harshman retired last year from his position as CEO of South Bend’s Logan Center, it marked the end of a 35-year career dedicated to helping countless families battle some tough challenges and win.

And Harshman happens to know a thing or two about winning. The roommate who took him to the children’s hospital to volunteer? It was a guy by the name of Rocky Bleier, who, along with Harshman, played on the 1966 national championship Notre Dame football team. Bleier also famously went on to advocate for people (mainly veterans) with disabilities; but at the time, he and Harshman were just two college kids who had no idea what the future had in store for them.

A standout on the football field at his Toledo, Ohio, high school, Harshman was recruited by legendary coach Ara Parseghian, who also was just getting started on his Notre Dame career.

“I came here Ara’s first year,” he says.

“How lucky is that?”

You could call it luck, or maybe a combination of that and good, old-fashioned athletic ability. The third team of the Parseghian era in 1966 never lost a game, putting up nine wins—and a famous 10-10 tie against Michigan State—and went on to become the eighth Notre Dame football team to bring home the national title.

“All we knew was winning,” Harshman says.

“I got to start in the last game against USC,” he says of that memorable moment his junior year. “I’d played defense all year and moved to offense for this one game because a bunch of guys were hurt. I was a second-team player all year. We won, and won the national championship, so that was really cool.”

He came back as a starter his senior year and played three games before he was sidelined with a knee injury for the rest of the season.

As his football career came to a close, Harshman began to consider the future. He stayed at Notre Dame to earn a master’s degree in education, then set out into the world with his high school sweetheart Betty, a nurse, whom he married in 1969. They first settled in Long Island, N.Y., where Harshman tried his hand in the classroom.

“I thought I wanted to teach school,” he says. “I come from a family of teachers.” Despite having two brothers and two sisters who were educators, he realized something important along the way. “I didn’t like teaching. I enjoyed a lot of things about the kids, but teaching English wasn’t fun for me.”

So they headed back to their Midwestern roots, to Toledo, where Harshman took on a different kind of role mentoring young people, this time working in juvenile parole with the Ohio Youth Commission. He had a caseload of boys who were coming home after being incarcerated in a state school. Those four years were eye-opening.

“I figured out how much I didn’t know,” he says. “It was really an education for me to see the life of poor people and inner-city families, crime and all that stuff.”

The Harshmans had three kids ages four and under when they decided to make another move. This time, they were drawn back to South Bend, where Dan hit the pavement looking for a job. Acting on a tip from the president of the local chamber of commerce, he paid a fateful visit to the Logan Center, an organization whose mission is to help people with disabilities in achieving their desired quality of life.

“I just walked in one day and kind of talked my way into the administrative secretary and made an appointment for an interview,” he says of that day in 1976. “It just worked out that they had an opening that I was willing to take for basically no money. But I liked what the organization was about and so I got this job and we moved to South Bend.”

Other than that one visit to the state children’s hospital with Bleier, Harshman hadn’t worked in the field of disabilities before. Starting out as Logan’s Title 20 coordinator, he first was responsible for securing federal funding for the center. Before long, the top job opened up and he threw his hat in the ring for the position of executive director.

“I had nothing to lose, and a lot to learn,” he says. “It was a huge step up to take this responsibility, so I did it.”

Although he calls the chain of events “serendipitous,” it did take a while for things to fall into place. “The joke was that it took me three years to figure out I had no business doing this job,” he says with a laugh. “But I just kept doing it and I loved it, so I learned quickly.”

As he was learning the ropes, he was forced to face and get over some of his own fears.

“Every parent worries,” he says, “they say it in code words: ‘I hope there are 10 fingers and 10 toes.’ Nobody ever wants to have a kid with a disability. But learning from the parents who faced that and dealt with that, and seeing many of them turn it around and say it’s a blessing in their lives—not everybody; that challenge is really tough on families—but many that I met turned that around and then were committed and advocated for better laws, more money and more services. That was exciting.”

Harshman is quick to give much of the credit for Logan’s success to the center’s talented staff and, of course, the many families who came through the center’s doors during his tenure.

“These people were so inspiring to me,” he says. “These families are still working hard when their kids are 40 years old. They fought for all these services; they fought people’s attitudes all time. A lot of people have misconceptions about mental retardation or developmental disabilities, so there’s always a need to educate, advocate and speak up for people.”

Among the many highlights of his career, there’s one that stands out above the others. In 1987, the International Summer Special Olympics were held at Notre Dame, with Logan leading the way in helping South Bend to get the bid.

Notre Dame became the Olympic Village for a week, with athletes, celebrities and some 20,000 volunteers descending on campus.

“Notre Dame and the community, we pulled it off,” Harshman says. “It came off beautifully.”

But after experiencing the thrill of the Opening Ceremony, the games took an unexpected and tragic turn.

“I never thought I’d be where I was the day after it started,” Harshman says.

“An athlete from Ireland had a seizure, fell down and hit his head, and was hospitalized. The committee asked me to handle that, to stay with him.”

As the days went on, the situation grew more serious.

“We didn’t know if he was going to live. The prime minister of Ireland came,” he says. “And in three days, the athlete died.”

With 4,000 athletes participating in the games, members of the planning committee knew there would likely be injuries. But they never imagined there would be a death. In spite of the tragedy, the event left a lasting impression on Harshman and many others.

“People still tell me all the time it’s one of the best things South Bend and Notre Dame did was to host the games. And I think it was,” he says. “It wasn’t depressing to see people with disabilities. It was fun and inspiring.”

Harshman returned to Notre Dame Stadium for another celebration last year, when the University marked the 45th anniversary of the 1966 national championship and brought the team out on the field for another round of applause from appreciative fans. The guys have stayed in touch through the years, keeping each other updated on life events that began with marriages, jobs and children in the early days, and have now evolved into retirement, vacations and grandkids.

“It gets better with age,” he says of the camaraderie of the team, which sadly had lost two members just before the anniversary celebration. “We all hope we make it to our 50th.”

As he settles in to retirement and time with his family, Harshman can reflect upon quite a legacy, although he’s too humble to think much of it. Those who know him celebrate his crowning achievements—among them a Logan Center that flourished under his leadership to become the beacon of hope it now is to so many families in the community; and the part he played in bringing glory to the Fighting Irish all those years ago. He’s got the championship ring, but you probably won’t ever see him wearing it.

“I’m low-key,” he says. “That’s just who I am.”

And that’s just part of the reason he is beloved by so many. His gentle nature and kind heart have inspired a legion of fans who admire him as a leader, a fighter and a champion in every sense of the word.

That’s just who he is.