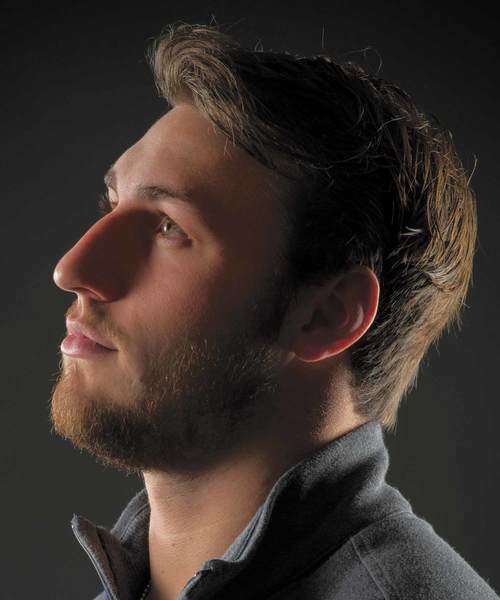

Danny Spond

When the game plan changes

The young man knew it was over before they could even get him inside the training room, long before any doctor peered into his eyes, took his pulse and led him through a battery of tests.

Football, the game he loved, the game he had played since he was 4 years old was now a part of his past. At best the next time he lined up on the grass might be years from now when he took his own kids out for a game of touch on Thanksgiving morning.

Danny Spond was going to be a star on the 2013 University of Notre Dame football team, no doubt about it for those who watched him get better game by game through his junior year during the 2012 unbeaten Irish regular season. He reminded fans a little of Michael Stonebreaker, one of Notre Dame’s all-time great linebackers who helped lead the Irish to the 1988 national championship. Both played with reckless abandon and, while not the fastest or most athletic players on their teams, they had that certain intangible that coaches like to call a nose for the football.

But Spond had something lurking inside him, something waiting to explode, a condition so rare and often confusing that the best minds in medicine still cannot get a grip on it.

To the best of his recollection, Spond never had anything more than a mild headache while growing up. In fact he was one of the healthiest kids you could find in Littleton, Colo. He was the prototype All-American boy at Columbine High School, where he pretty much did it all—played linebacker, quarterback, kicked extra points and punted.

In 2009, the Denver Post called him the best athlete in Colorado high school football. The world was his oyster and college football coaches came calling by the dozens, promising him an unlimited future if he would just sign with them. Spond, a devout Catholic, pretty much had his mind made up that he was going to Notre Dame so he could be a student first and, oh yes, a football player too. In hindsight he says it was a blessing beyond anything he could have imagined when he came to South Bend with dreams of gridiron glory.

Most of us probably know someone who suffers from migraine headaches and those afflicted will tell you there is no adequate way to explain the effects unless you’ve had one yourself. And you don’t want to find out personally because a migraine, if boiled down to one word, is debilitating.

The only knowledge Spond had of migraines was what he had others tell him. Then, in the summer of 2012, seemingly out of nowhere he was literally brought to his knees in an instant. He thought his head was going to blow up, his stomach felt like it could erupt and his vision blurred to the point that he thought there might be a thousand players out on the practice field. And he was really scared because he didn’t have a clue what this could be all about. Notre Dame’s doctors were quick to react, but they knew they had something most unusual on their hands, and they turned to the some of the best neurologists in the country for advice.

What they were beginning to find out is they might be dealing with something so rare there is no body of evidence to pore over and no reported cases of an American athlete ever so deeply affected by migraines. But the condition went away and eventually Spond was carefully cleared to play in 2012. And how relieved Spond was as he went through winter workouts and the 2013 spring semester as if nothing had happened.

But the doctors were on high alert, watching his every move during spring ball, when he had another migraine, not as devastating as the first. Without a textbook to turn to, they were reaching the conclusion this was not the garden-variety migraine, which is bad enough, but something medically known as a hemiplegic migraine. Like any other condition so rare it has often been misdiagnosed because it has all the appearances of a stroke or epilepsy or vascular disease out of control. At this point the doctors tell the coaches that Spond’s football career is on a very short leash and everybody agrees if there is even a hint of another problem they are going to tell him the unvarnished truth—that we need to take care of you as a human being, not as a football player who can help the team. Notre Dame’s doctors look for the best preventive medication to try and stop the migraines.

When summer camp for 2013 rolled around, the team started off with a week away from campus in Marion, Ind.—planned as a bonding period for a new team seeking a similar chemistry coming off a 12-1 record a year ago. Spond had never heard of Marion before, but now he will never forget the place because that is where his football career came to an end when he was hit with a migraine so severe one doctor suggested it was the scariest thing he had ever seen on a practice field. Through the excruciating pain, the quivering arms and legs, the near blindness and the sweat that had nothing to do with the summer heat, Spond knew full well he did not need coach Brian Kelly or any doctor to deliver the news that he was no longer going to be able to play football.

Sitting across a table from Spond halfway through the 2013 season there are a couple of things that strike you right away. He looks terrific, almost as if he could suit up for a game as soon as we are done talking. He is one of those people who just carries himself like an athlete with the good looks of guy who could be on the cover of GQ Magazine. But, he tells me, it was only weeks earlier that he was walking with a cane because of the stroke-like symptoms from the migraines and taking eight pills a day just to keep his body and brain in some sense of balance.

What he really wants to talk about is Notre Dame, “this place” as he called it, that he says has not only made him a better person but someone who can put what happened in a positive perspective and be the best version of himself he could ever possibly be. Maybe, he says, this is a challenge that is testing me, pushing me to my limits, giving me the mental strength I need for my game of life.

For a while he thought what happened was a tragedy, but now he says it fails in comparison to real tragedies in this world. “What about a loved one being taken too early, a parent losing their job and not knowing how to provide the

next meal for their family, or a woman being diagnosed with breast cancer with children at home who depend on her—those are the real tragedies in this game we call life,” he says.

It is hard to imagine a young man who just turned 21 having such a positive, well-balanced outlook on life when he is just months away from having his dreams derailed by a medical condition so severe, so painful that he says he does not have the words to adequately describe it. In the weeks after the third attack he looked into a mirror and thought there is no way it could be him swallowing all of those pills and pressing his weight against a cane just to keep his mind and his body composed.

Maybe it has something to do with where he came from—Columbine High School in Littleton, Colo. Spond was just a boy when the slaughter occurred, but he says it touched everyone in the community and going to Columbine where he was a leader on and off the field gave him a better perspective on life. That tragedy had such an impact on him that he carried it to Notre Dame and helped him understand there is no justifiable reason to feel sorry for himself.

And, in reality, Spond’s Notre Dame football career didn’t really end after all. He still attended every meeting, assisted at every practice and wore a headset during games. He particularly spent his time mentoring freshman outside linebacker Jaylon Smith, who came on in Spond’s absence to be a rookie stalwart.

When the Irish traveled to play Air Force, Colorado product Spond walked to midfield with Irish captains Bennett Jackson, TJ Jones and Zack Martin for the coin toss. After the 45-10 Irish victory, Kelly presented Spond with the game ball in the locker room.

I ask Spond if he could find time to send me some personal thoughts on all of this, and I am surprised to turn on my computer the next morning to find email from him.

This is all you need to know about the kind of man Spond is, in his own words.

“Maybe my challenge is testing me, pushing me to my limits, giving me the mental strength I need, for my game of life. I might not have 80 thousand fans cheering for me on Saturdays, I might not have the glory of being an active Notre Dame football player any more, but I do have the ability to win each day for myself so I can look in the mirror and not let my personal tragedy define me. I believe when you prepare for the unknowns in all areas of your life, nothing can defeat you.”

It is safe to say Danny Spond will leave Notre Dame undefeated.