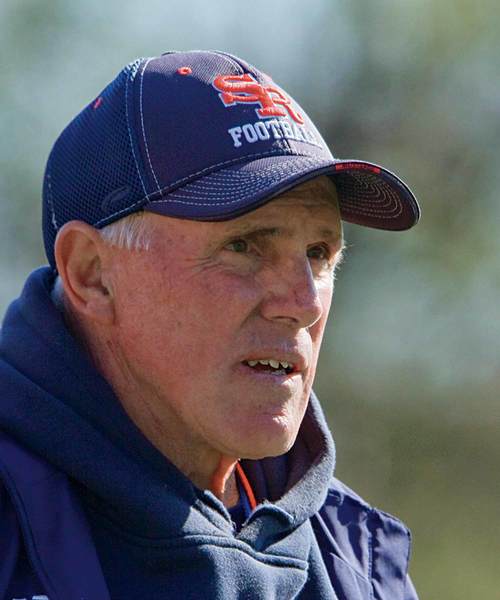

Jay Standring

50,000 kids have called him their coach

Jay Standring fulfilled a dream every time he ran through the tunnel and onto the field to play football for the Irish at Notre Dame Stadium.

The crowd’s thunderous roar and the call-to-arms majesty of the “Victory March” combined o make his heart beat a little faster, every time.

A defensive back from Leo High School on Chicago’s South Side, Standring earned two letters on Ara Parseghian-coached University of Notre Dame teams that were a combined 15-4-2 in 1968–69. He intercepted three passes in his career and experienced history with the squad that lost to Texas in the 1970 Cotton Bowl—the Irish were making their first bowl appearance in 45 years.

To this day Standring treasures his Notre Dame experience as “one of the highlights of my life.”

It might be a stretch to say he gets the same charge out of watching a 14-year-old high school freshman take his first nervous steps toward becoming an athlete, but maybe not. Jay Standring was that kid once. Not a day passes that he doesn’t remember the people who helped make a life in sports a realistic goal for him. From the day he graduated from Notre Dame with a sociology degree in 1970, he has been repaying the favor as a coach, mentor, teacher and role model to thousands of youngsters, regardless of their athletic aptitude or interest.

“I have a lot to be thankful for, beginning with the way my parents raised me,” Standring says.

“I like to see kids get the same opportunities I had.”

For a time, Standring thought his future might be in college coaching. To facilitate a move up the ladder, he enrolled in graduate school and earned a master’s degree in physical education while on the football staff at Northeastern Illinois University. No sooner had he completed the requirements than Northeastern dropped football. Standring took it as a sign. He has been a high school teacher and coach ever since, by choice an entry-level coach, currently handling the freshman football and baseball teams at Chicago’s St. Rita High School.

He’s in his 20th year at St. Rita, teaching theology and physical education, after a lengthy stay at Leo, his alma mater, and a brief one at Mount Carmel. The three schools are Chicago Catholic League rivals.

“I like to teach fundamentals—that’s why I prefer working with the young guys,” Standring says.

“Teach them the proper way to play the game, and try to make it a good, positive experience for them. That’s what I always got from my coaches.”

To watch Standring on the practice field is to appreciate a man in his element. Some of the 50 kids on his roster had never played a down of tackle football before coming to St. Rita, and at least that many won’t play another down after their freshman season ends. But Standring knows them all by name and seems to have an equal investment in each of them, from future stars to future physics majors.

He is constantly in motion during a scrimmage, offering pointers on footwork or positioning or technique after each play. His voice is audible in all corners of the field, but he’s not shouting; he’s instructing, encouraging.

“I never heard my parents swear, and I don’t think I ever had a coach swear at me, whether it was Bill Doherty at St. Cajetan’s, Bob Hanlon at Leo or Ara at Notre Dame,” he says.

“That always stuck with me.”

At 63, Standring is almost 50 years older than his fresh-faced charges, and he has been doing this longer than some of their parents have been alive. But he is still the most enthusiastic “kid” on the field, high-fiving players and fellow coaches and stopping practice at one point to order up a “double-swoosh” salute to a backup linebacker who intercepts a pass and “takes it to the house” against the first-team offense.

The scrawny youngster tries to shrug off the attention, but he’s beaming beneath his oversized helmet. If he never does another thing on a football field, he’ll always have this memory. That matters to a kid. Jay Standring knows.

“Football is a tough game,” he says.

“If the kids can’t enjoy themselves out here, what’s the point?”

He can’t even guess how often similar scenes have played out over the 40-plus years he has been doing this, but he never tires of them.

“How many games?” Standring repeats the question and sounds puzzled, as if it had never occurred to him.

“Oh, gosh, I don’t know. A lot, for sure. Hundreds.”

His record?

“I have no idea. I’ve never really kept track. Wins and losses aren’t that important at this level. I’ve always been a competitor, and I played to win. But when you’re coaching kids this young, it’s more important that they learn how to play the right way. Emphasize sportsmanship and values and try to make sure it’s a positive experience for them. You want them to be rewarded for their effort, but what they take away from the experience of playing and competing matters more than the wins and losses.”

St. Rita grad Ed Leiser played freshman football for Standring in 2000 and later won varsity letters in football and track. A 2008 Illinois State graduate, he is now Standring’s St. Rita colleague, working in development, alumni relations and recruiting.

“I thought I was really lucky to play for Jay because he taught us so much about football, but as I got older I realized football was only part of it—he’s developing you as a total person,” Leiser says.

“He’s the most upbeat, enthusiastic guy I’ve ever been around. Playing for him was a totally positive experience, and it’s great to be able to work with him. He’s the first one here and the last one to leave every day.”

Standring’s commitment to the school is a family affair. His wife, Julie, helps out in the athletic department, and sons J.J. and Paul were two-sport standouts who went on to compete in college: J.J. punted and pitched at Northwestern, and Paul played football at Wisconsin. Julie comes from a family of athletes—brother Tom Omiecinski was a running back at Miami who played against Notre Dame in the 1960s. She has never regretted sharing her husband with hundreds of kids each year.

“It’s who he is,” she says. “He loves working with the kids. It makes him happy. And he’s really good at it.”

For as many games as Standring has coached, he has probably officiated twice that number. Before a chronic case of turf toe made running a problem three years ago, he was one of the busiest basketball referees in Chicago, working half a dozen games a week or more on the grammar school and high school levels.

Parents, coaches and other would-be experts rarely questioned his competence and never his effort, but he wasn’t exactly Mark Buehrle–efficient in running a game. Ever the coach, Standring went beyond enforcing the rules; he would explain and/or demonstrate each violation to each offender: a block rather than a charge, a moving screen, a dragged pivot foot, etc.

“Sometimes I’ll have people stop me in the store and ask me if I used to be ‘the referee,’ and then they’ll talk about a game they played in or their kids played in that I did and they remember,” Standring says.

“That’s pretty cool.”

He may have retired his official’s whistle, but he keeps his hand in basketball by keeping the scorebook at St. Rita’s sophomore and varsity games. When he’s not teaching, coaching or scorekeeping, he’s baking his special-recipe cookies that the St. Rita Fathers’ Club sells at games to raise money.

“Jay is a human dynamo,” says Brendan Conroy, St. Rita’s principal, who has known Standring since they taught together at Leo more than 20 years ago.

“The kids love him because they know he really cares about them and he’s there for them, whether it’s a team he’s coaching or a group he’s not directly connected with. He’s always upbeat, always positive, always encouraging. He’s just a terrific guy.”

And a Domer forever.

Standring runs a sports camp for grammar-school kids at St. Rita every summer, and a bus trip to Notre Dame is one of the highlights. This year the group met senior linebacker Darius Fleming, a former St. Rita Mustang who played for Standring.

So did Mike Kafka, an ex-Northwestern standout who is the backup quarterback for the Philadelphia Eagles. So did Ryan Donahue, a kicker who won a scholarship to Iowa and now punts for the Detroit Lions.

So did Pat and Mike Shanahan, the sons of Jim Shanahan, who was Standring’s first quarterback at Leo.

“I guess I have been at this for a while,” he says.

The second oldest of Jack and Betty Standring’s six children, Jay took to heart his parents’ admonition to stay active. He was an all-city halfback, a starter on a Catholic League championship basketball team and a 12-time letter-winner at Leo before enrolling at Notre Dame.

There he displayed an alarming propensity to put his body at risk. He broke his leg playing rec-league hockey as a freshman and fractured his shoulder making a kamikaze play to break up a screen pass in practice a year later, missing two seasons.

He hasn’t been as reckless as a husband and father, but accidents keep finding him anyway. Standring was struck by lightning when a freak thunderstorm blew through St. Rita’s practice field 10 years ago. Miraculously, he escaped injury, but months later he slipped off an elderly neighbor’s roof while cleaning her gutters and suffered another broken shoulder.

Yet those who know him best say Standring hasn’t slowed down a bit. He begins each day with Mass at St. John Fisher Church, then heads to St. Rita for a full day of teaching, coaching and inspiring generations of impressionable, grateful kids.

“Why should I retire? I’d have to grow up,” Standring says with a smile as he looks around St. Rita’s spacious campus on a glorious fall afternoon.

It’s closing time, so to speak, and dozens of parents roll up to claim their football players, soccer players, cheerleaders, golfers, etc. Judging by the number who toot the horn and wave or come by to greet him, Standring could have a second career as a politician were he so inclined. He is not.

“This is my life,” he says, “and it’s been a good one.”