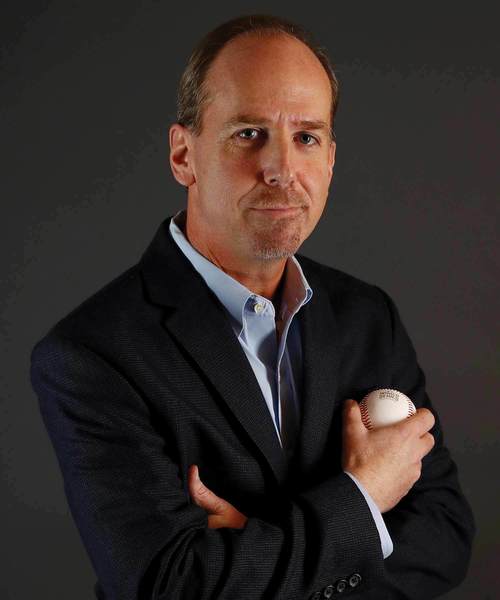

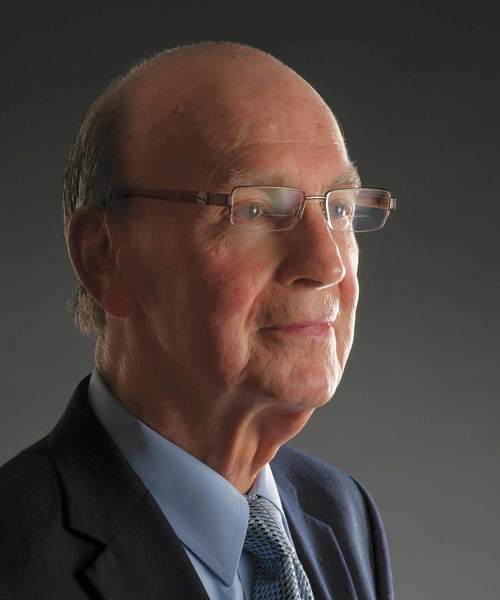

Jim Gibbons

A man for all seasons

You can’t find anyone associated with the University of Notre Dame who has a bad thing to say about Jim Gibbons—which is saying something, since Jim Gibbons knows everyone.

That isn’t to say he’s a glad-hander who has attempted to ingratiate himself at the University. Rather, it’s because he has been such a kind, caring and considerate representative of the University for more than a half-century.

“I was a colleague of Jim’s for more than 20 years, and to say there will never be another like him is the ultimate understatement,” said Dan Reagan, a former associate vice president for University Relations. “In my mind, he was, and continues to be, this tremendous blend of intensity and sensitivity, and Notre Dame has benefited from it greatly.”

Gibbons worked at Notre Dame for 43 years, six in athletics as an assistant baseball and basketball coach, and then for 37 in University Relations, primarily as the assistant vice president and director of special events and protocol.

“From his days as an athlete and coach, Jim’s intensity would show in the many pressure-packed events he orchestrated,” Reagan recalled. “Whether for a head of state, (University presidents) Fathers (Theodore) Hesburgh or (Edward “Monk”) Malloy, or countless Trustees and benefactors, Jim had one goal: perfection. And if he didn’t achieve it every time, he came very close.”

But before beginning his career at Notre Dame, Gibbons was a standout baseball, basketball and football player at Mt. Carmel High School on Chicago’s South Side. He was widely recruited in all sports, but his football and basketball coaches—Bob McBride, later an assistant for Frank Leahy, and Johnny Jordan, later the head basketball coach for the Irish—were Notre Dame graduates, and, Gibbons said, “They weren’t about to let me go anywhere but Notre Dame. It was fate.”

Of the three sports in which he excelled, it was baseball that Gibbons loved most. “All I wanted to be was a professional baseball player,” he said.

So, naturally, he came to South Bend on a football scholarship, albeit with the promise that he could also play basketball and baseball.

“When we got to the spring of my freshman year, I realized (Frank) Leahy wasn’t going to let me play baseball,” Gibbons said. “I had to play baseball. That’s all I ever wanted to do.

“I was paralyzed (with fear), but I went to him and he could not have been nicer. He set up a half scholarship in basketball and a half in baseball. That’s why I ended up playing both sports.” Gibbons was a starter for both Irish teams, but, again, it was baseball where he had the most success as a pitcher. At the end of his senior year, he realized his dream of playing professionally, signing a contract with the Philadelphia Phillies.

“I got the most money they could give in those days to sign,” Gibbons said. “I don’t remember exactly how much it was, but it wasn’t much.” In the summer of 1953, Gibbons pitched for a Phillies farm team and remembers facing future Hall of Famer Frank Robinson.

“He hit a home run off me that is still going,” he said. “It must have gone 600 feet if it went a yard. That was my baptism.”

Gibbons’ playing career was short-circuited after the season when he was drafted into the United States Army. He spent the next two years in New Orleans as a military policeman and then returned to Mt. Carmel to teach civics and speech and to coach baseball and basketball.

Before his first year back at Mt. Carmel was over, Notre Dame director of athletics Moose Krause called. “He said he was looking for an assistant basketball and baseball coach who had monogramed at Notre Dame,” Gibbons remembers. “He asked if I would like to do it, and I told him I would walk back to take the job.

“I went to South Bend to meet with him and we talked and talked, and he never mentioned anything about money. I was making $4,200 a year at Mt. Carmel, teaching and coaching. He said, ‘Jimmy, we’re going to pay you $3,800.’ I wasn’t married yet, but I knew that wasn’t a lot. Moose said to not worry about it. He would let me eat at the training table and live in the firehouse. Frank Leahy had lived in the firehouse during the week, so he didn’t have to drive back to his home in Michigan City, so I figured, if it was good enough for him, it was good enough for me.”

And so it was that Jim Gibbons returned in 1956 to his alma mater, never to leave.

Over the next six years, Gibbons assisted Jordan with the basketball team and Jake Kline with baseball. With both teams he coached Ron Reed, who went on to play professionally for two years in the NBA with the Detroit Pistons and for 19 years in baseball with the Braves, Cardinals, Phillies and White Sox.

Gibbons also successfully recruited Washington, D.C., basketball standout Edward Malloy to Notre Dame. While Malloy’s basketball career was, by his own admission, “undistinguished,” he certainly made his mark at the University. As Father Malloy, he served as its 16th president, from 1987 to 2005.

Another standout to play for Gibbons in both sports, though only briefly, was Carl Yastrzemski, who came to Notre Dame in the fall of 1957 but then soon signed with the Boston Red Sox, for whom he played 23 Hall of Fame seasons.

“If you’re wondering if I knew he was going to be a Hall of Famer, no, I didn’t,” Gibbons says with a smile.

Yaz returned to Notre Dame for three years to continue his studies and ultimately earned his degree from Merrimack College in North Andover, Mass. He and Gibbons have remained lifelong friends, fishing together most every summer.

Gibbons’ coaching career was on an upward trajectory in the early 1960s. In addition to his work at Notre Dame, he also managed a Pittsburgh Pirates Rookie League team in Kingsport, Tenn., in the summers of 1961 and ’62.

But then he nearly died.

The stress of coaching led to a bleeding ulcer in 1962 that landed him in St. Joseph Regional Medical Center in South Bend, where he became deathly ill. Doctors were able to control the bleeding over many months, but he was told to find another career.

“They told me not to coach anymore because of the ulcers,” Gibbons said. “I felt as if my whole life had ended. I had nowhere to go, no job.”

Gibbons and his wife of four years, Betty Ann, considered going back to Chicago, but he decided to touch base with a few people on campus to ask if any jobs were available.

“I spoke to one University administrator, who told me to not leave. He set up a lunch meeting with some people on campus and I walked out of that with a job in the public relations office. I was an assistant, helping with a variety of ‘gopher’ jobs. My first assignment was to take (longtime Coca-Cola Company executive) Don Keough and his daughter Shayla on a tour.”

It must have been a great tour. Keough became a member and chair of Notre Dame’s Board of Trustees, and Shayla now also serves on the board. The family has been one of the University’s most generous benefactors.

Gibbons is indebted to the late Rev. Edmund Joyce, C.S.C., the University’s executive vice president from 1952 to 1987. During his illness, he said, “I did not set foot on campus for a year and a half, and Ned Joyce never took me off the payroll. He saved us.”

When Art Haley, the director of public relations, retired, Gibbons became the University’s chief protocol officer, charged with organizing dedications, convocations, dinners and special visits for dignitaries of every stripe. He planned the first-ever inauguration of a Notre Dame president in 1987 (that young Malloy fellow he had recruited in the late 1950s), and assisted in the arrangements for campus visits by four U.S. presidents as well as numerous international heads of state.

When President Gerald Ford received an honorary degree from Notre Dame in 1975, members of his advance team approached Gibbons about coming to work in the White House. He declined, saying, “I was smart enough to realize that when he left office, I’d be out of a job.”

By Gibbons’ count, he was involved in the dedication of 38 buildings on the Notre Dame campus, starting with the library in 1963. He is most appreciative of the many friendships he developed through the years with Notre Dame Trustees, leaders and benefactors.

“Of course,” he says, “I kid that they all liked me because I had tickets, rooms at the Morris Inn and parking passes.”

Gibbons was awarded a Presidential Citation in 1979 for outstanding contributions to the University and in 1988 received the Notre Dame Alumni Association’s James E. Armstrong Award, which honors a University graduate and employee for distinguished service. In addition, he has received the Edward “Moose” Krause Award from the Notre Dame Club of Chicago, and William and Janie Kelly of Southern Pines, N.C., established the James V. Gibbons Scholarship for Notre Dame students who demonstrate loyalty, spirit and intellectual and athletic achievement.

In addition to his full-time job, Gibbons also refereed college basketball games for many years and for more than two decades served as a radio and television color analyst on Atlantic Coast Conference, Missouri Valley Conference and Notre Dame basketball games.

And family always has been a priority for Gibbons. He and Betty Ann have four adult children, Nancy, Brian, Kevin and Mike.

Upon his retirement from the University in 1999, Gibbons was sure of one thing: “I could not just stop working.”

He contacted St. Joseph Regional Medical Center, where he once lay at death’s door, and asked about serving as a volunteer. The hospital quickly took him up on the offer, and for the next eight and one-half years for six hours a day, five days a week he called recently discharged patients to ask how they were doing and to inquire about their hospital experience. He estimates he made 41,000 calls.

“I felt it was a real ministry,” he says.

When the hospital relocated several years ago, Gibbons was asked to start making room visits with patients, again checking on their care.

“I would always talk to them about my years at Notre Dame,” he said. “So many had worked at Notre Dame or knew someone who had. That really helped break down barriers. Then I would be able to talk to them about the quality of their care, service and treatment, and whether they were being respected and listened to by everyone—from food services to nurses, doctors, everyone.”

William Sexton, who as vice president for University Relations worked with Gibbons for more than 15 years, says St. Joe could not have selected a better person for the task.

“There is no one more caring and compassionate than Jim for those facing illness, loss or loneliness,” Sexton said. “His role is not writing a note, signing a visitor’s book or placing a brief call. He gives himself over completely to the task of healing a friend, a patient in the hospital where he has become a legend, or just anyone he comes to learn needs something. His caring is so very authentic and enduring for those so blessed to receive it.”

Reagan echoes those sentiments with a telling story:

“Jim pays close attention to the needs of others, especially when there are challenges—an illness, the death of a loved one, or someone just to listen. One example of the exceptional reputation Jim carries occurred at an event at the top of the Hesburgh Library where we were holding an intimate gathering of benefactors with Father Malloy. Jim was unable to be there, which was a rarity, and asked if I could stand in for him. As the guests arrived, I greeted one Chicago-based, longtime donor with, ‘Hi, I’m your Jim Gibbons for the evening.’ He looked at me and in a direct but not mean-spirited voice said: ‘You can only dream about being Jim Gibbons.’ My ego wasn’t bruised because I knew he was right. I could never be Jim Gibbons, nor could anyone else.

“A couple of years later the same benefactor passed away suddenly. The funeral was large, and because of the suddenness, very emotional. Many University officials attended, but the one person the family wanted to see the most was Jim—and there he was, comforting the entire family, saying exactly the right things, letting them know how much he cared. That was not unique for Jim, as he has been there over and over again for so many at Notre Dame.”

Gibbons was diagnosed with cancer on his left tonsil and in the lymph nodes in his neck in the fall of 2012. Radiation and chemotherapy treatment have eradicated the cancer, but it robbed him of his senses of smell and taste, and he has no saliva.

But it couldn’t take away his sense of service to others. Now, he spends each morning at Holy Cross House, the Congregation of Holy Cross retirement facility across St. Joseph’s Lake from Notre Dame, assisting the staff and attending to those in need.

Just like always.