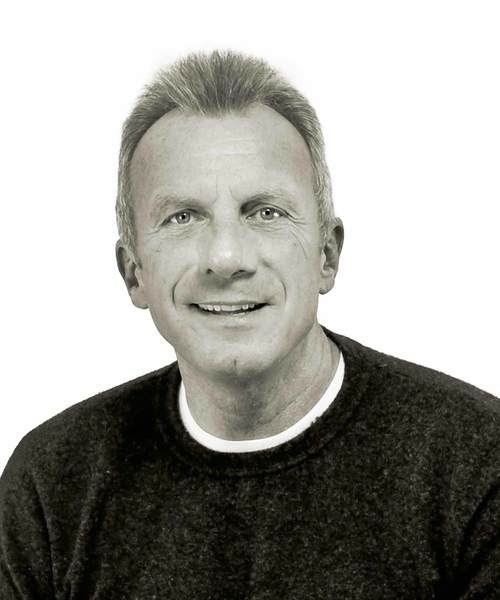

Joe Montana

It’s hard to be anonymous when your name is Joe Montana

Joe Montana won a national championship at Notre Dame and four Super Bowls with the San Francisco 49ers, playing quarterback with an imperturbable élan that personified grace under pressure and made him synonymous with big-game excellence.

If he’s not the best ever at football’s centerpiece position, he’s certainly in a highly selective team picture of the all-time greats. The name alone carries a tinge of something mystical … a Western movie hero, perhaps.

“If you had one game you had to win, Joe Montana is your quarterback,” 49ers teammate Randy Cross said.

Hard to believe a man who seemed born to do what he did so well was once a scared, skinny, homesick freshman, not sure if he fit at Notre Dame and wondering if he’d be better off someplace else.

“I was one of about seven freshman quarterbacks, and I played my way down to seventh string,” Montana recalled of his 1974 arrival. “I didn’t doubt my ability, but I wondered whether I was ready for a place like Notre Dame. Everybody else was good, and really big—especially the defensive guys.”

Ara Parseghian had recruited Montana out of western Pennsylvania quarterback country. When Ara’s retirement brought Dan Devine to South Bend, Montana’s future seemed less promising than a Chicago Republican’s—coaches like to go with their own guy at the game’s most important position.

“Devine probably wondered why I was recruited,” Montana said.

It was Irish fencing coach Mike DeCicco, an academic advisor to Notre Dame athletes and the father of Joe’s teammate/roommate Nick DeCicco, who convinced Montana to stick around, that his day would come. And it did—as a sophomore in 1975, he directed the Irish to comeback victories over North Carolina and Air Force.

He had planted the seeds of the Joe Montana legend, only to encounter another setback. A shoulder injury cost him the 1976 season and his place in Devine’s heart—Montana was number three on the depth chart going into 1977. Called upon with the Irish facing a 24-14 deficit against Purdue in week three, he delivered 154 passing yards and 17 points in the final 11 minutes for a 31-24 victory.

“The players were practically jumping up and down when Joe came into the game. They started slapping him on the back before he had taken a snap,” recalled Roger Valdiserri, Notre Dame’s longtime media relations director. “I was sitting next to my Purdue counterpart, and he asked me what was going on. I said, ‘That’s Joe Montana, and you guys are in trouble.’”

The Irish would not lose again that season, nailing down the national championship with a 38-10 thumping of top-ranked Texas in the Cotton Bowl. The scared, skinny, homesick freshman was now a poised, accomplished star, partly because Mike DeCicco’s belief in him overcame Montana’s self-doubt.

“Notre Dame is a hard place to leave, fortunately,” he said. “It’s not really big, but it’s sort of overwhelming because it’s Notre Dame, and you’re always mindful of what that means. You want to be the best, and you want to prove it by playing against the best.”

An early-season loss to Missouri derailed Notre Dame’s hopes of repeating as national champion in 1978, but two more vintage comebacks enhanced the Montana legend. The Irish trailed a great USC team 24-6 in their season finale when Montana got busy, completing 11 of 15 passes for 196 yards and producing three scores for a 25-24 lead. But a bad call on a fumble went against the Irish on the Trojans’ final possession, and USC kicked a field goal with two seconds left for a 27-25 victory.

Then there was the 1979 Cotton Bowl against Houston, played in the aftermath of a freak ice storm. Before he hooked up with Dwight Clark on “The Catch” three years later, this was Montana’s signature moment. The Irish trailed 34-12 when a weak and wobbly Montana came out of the locker room, fortified by chicken soup to ward off flu-induced hypothermia. In the last game of his college career, he produced 23 points in the final 7:37, rallying the Irish to a 35-34 victory that still gets ND fans tingling.

“Joe had a gift, an aura,” Valdiserri said, “and his teammates fed off it. But he was a tough interview because he didn’t like to talk about himself.

“The only time I ever saw Joe nervous was on a flight we were taking back to Pennsylvania for a banquet. We hit a rough patch, the plane dropped about 10,000 feet and our heads banged into the overhead compartment. I looked at Joe and he was whiter than I was.”

Turbulence in mid-air was a scary proposition. On the ground it didn’t seem to exist, no matter the stakes.

“I was a competitor. I hated to lose, and I think that drove my confidence and my concentration to where I played better in those situations,” Montana said. “I wish I could have played like that all the time.”

The pros probably wished he had, too. While big-armed flingers like Jack Thompson, Phil Simms and Steve Fuller were first-round picks in the 1979 NFL draft, Montana lasted until the third round, going to the 49ers as the fourth quarterback and 82nd player taken. It was the best thing that could have happened to him. With his nimble feet, deft touch and uncanny poise and vision, Montana became the ideal triggerman for the controlled passing game Bill Walsh used to transform football.

“I knew he was really smart, and an excellent teacher,” Montana recalled of his first meeting with the cerebral 49ers coach. “And you had to love that offense. If you couldn’t go downfield, you stayed underneath. Somebody was always open.”

It was Dwight Clark in the back of the end zone against Dallas in January 1982, “The Catch” sending the 49ers on to Super Bowl XVI and a 26-21 victory over Cincinnati. Three years later Montana won a shootout with the heralded Dan Marino as the 49ers buried Miami 38-16 in Super Bowl XIX. Four years after that he directed a last-minute, length-of-the-field drive to beat Cincinnati again, strengthening his case as the best ever with the game on the line. The following year he looked like the best ever, period, with a 297-yard, five-touchdown strafing of Denver.

Montana was four for four in Super Bowls and MVP in three of them, with 11 TD passes, no interceptions and a 127.8 passer rating. The great Willie Mays notwithstanding, he might be the most popular athlete in San Francisco history—the 49ers occupy a special place in the city’s heart because they were born and bred there, not transplanted from elsewhere like the region’s other pro teams. As he’d done at Notre Dame, Montana did his best to remain a regular Joe.

“He’s the most normal famous person I’ve ever been around,” said Jerry Walker, the 49ers’ former media relations director and now a team historian.

“By the second Super Bowl, we were getting two of those post office bins full of fan mail every week. My wife was on a maternity leave from her job coaching gymnastics at Stanford, so she came in to help. A lot of guys couldn’t be bothered with answering fan mail. Joe was very conscientious.

“We got a follow-up letter from a girl one time thanking Joe because the birthday card he’d signed for her sister showed up on her birthday. We couldn’t worry about being timely because there was so much mail to go through, but Joe took it on himself to make sure this card got there on time.”

As the 49ers became the dominant team in pro football, Walsh stressed that no one man was above the team. Montana bought into that belief. His one-of-the-guys persona helped account for his popularity, along with his cold-blooded fearlessness in the tightest situations.

Before embarking on the 92-yard drive that beat Cincinnati in Super Bowl XXIII, Montana pointed out a celebrity in the stands to teammate Harris Barton—comedy actor John Candy.

“Harris was a people-watcher, and all week he was talking about who he’d run into,” Montana said. “He hadn’t mentioned John Candy, so I was just letting him know he was there.”

Then it was time to go to work. “Joe had that look in his eye,” Cross said.

Since retiring from the Kansas City Chiefs after the 1994 season, Montana has been as busy as he cares to be with product endorsements, speaking engagements and a variety of business ventures. He has tried to provide as normal a life as possible for Jennifer, his wife of 25 years, and their four children: Alexandra, Elizabeth, Nathaniel and Nicholas. “I missed a lot when the girls were growing up because I was still playing,” he said.

Montana insists he never found the demands of fame all that stifling, in part because most Bay Area residents aren’t obsessed with celebrity. A conversation with Magic Johnson was a useful public relations primer.

“He told me he was out with his son one time, and he started signing autographs and talking to people like he always did,” Montana said. “His son finally pulled on his sleeve and said, ‘Dad, are you with all these people or are you with me?’ From that point on, when he was out with his family he was with his family, and the public just had to accept it. I tried to do the same thing. I was a football player, but I’m also a dad. When we were at Disneyland, I stopped holding the bags and went on the rides with my kids.”

Ali and Elizabeth Montana are Notre Dame graduates. Nate is a junior backup quarterback for the Irish, and Nick is a redshirt freshman quarterback at the University of Washington. Broadcaster Ted Robinson, the 49ers’ radio voice, has known Montana for more than 30 years—they were classmates at Notre Dame—and he says Montana has managed nicely as a family man.

“He and Jennifer have been together 25 years, they’ve raised four really good kids … I think Joe is really comfortable with who he is right now, really happy with where he is,” Robinson said. “And he should be. He’s handled it all very well.”