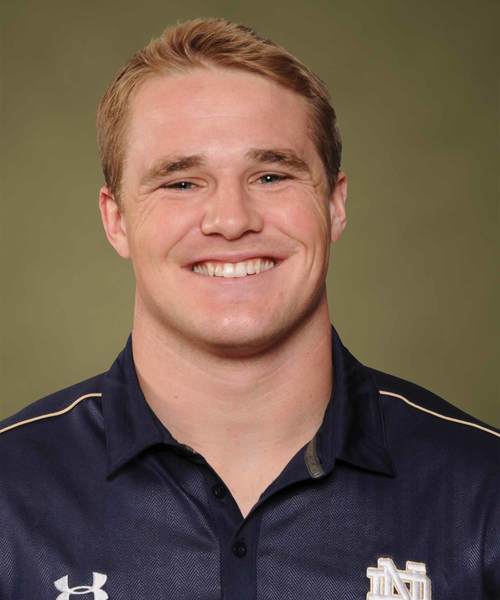

Joe Schmidt

Still living the dream

Joe Schmidt has three siblings, all sisters, and the University of Notre Dame senior middle linebacker is pleased to tell anyone that “my sisters are all more athletic than I am.”

There’s Catherine, 31, the oldest, a former middle-distance runner for the Irish; Mary Grace, 23, who played soccer at Texas A&M; and Margaret Ann, a high school senior who also appears headed to College Station, Texas, to play soccer for the Aggies.

Schmidt, who in 2014 was one of the leading tacklers for the Fighting Irish, is certainly a terrific football player. Yet, as you speak to this charismatic young man from Orange County, California, you notice he appears to be contradicting himself. Not about the athleticism. No, about his number of siblings, because more often than not Schmidt reflexively mentions “my brother Greg.” Is this a stepbrother, you wonder, after the third mention.

“No,” Schmidt says with a smile. “He’s actually my brother-in-law, Catherine’s husband. His name is Greg Lopez. We’re so close that I just refer to Greg as my brother.”

“We’re kindred spirits,” says Lopez, who is in residency, training as an orthopaedic surgeon in Southern California.

“My husband has always been my brother’s biggest fan,” says Catherine Lopez, whose last-minute decision to choose Notre Dame over USC when she was a high school senior fostered these relationships. “The first time Greg met my little brother, he told him, ‘You’re going to be the quarterback at Notre Dame.’”

Schmidt is the quarterback at Notre Dame—of the defense, at least. He is also the team’s quarterback when it comes to philanthropy, having helped establish the school’s chapter of Uplifting Athletes, a nonprofit that aligns college athletes with patients suffering from rare diseases. In 2014 Schmidt was Notre Dame’s nominee for the AFCA Good Works Team as the most charitable player on its roster.

When asked whether, as a student at an academically rigorous institution who is also the field general for the football team’s defense, he might forestall immersing himself in philanthropic work for a few years, Schmidt says, “Why wait? Why wait to help people?”

But let’s return to Catherine, then a senior track star at Mater Dei High School in Santa Ana, California. She made a short drive up Interstate 5 to visit USC and fell in love. “I bought all the T-shirts,” she says. “I thought, ‘I’m going to go to USC!’”

However, Catherine wanted to visit Notre Dame as well. Her parents, Joseph and Debra, gave their blessing provided their SoCal daughter went on her pilgrimage in January, when South Bend is at its most inhospitable.

“When I showed up (in January 2002), they were in the midst of record-breaking warmth,” says Catherine. “The people I met were the kind of people I saw myself wanting to be like. I fell in love.”

Catherine Schmidt chose Notre Dame, which offered her a spot on its track team as a non-scholarship recruited walk-on.

Two winters later the Schmidt family arrived en masse in South Bend to visit Catherine and see her take part in an indoor track meet. This time the weather was more seasonable and, as her little brother recalls, there was a foot of snow on the ground. As the Schmidts trudged across campus before the meet, they passed Notre Dame Stadium.

“Wouldn’t it be great if we could go inside?” asked Schmidt, then 10 years old.

It just so happened they could. Catherine’s boyfriend, Lopez, played shortstop for Notre Dame’s baseball team and had an access card to the stadium. He swiped the card and suddenly the five of them were trespassers.

As his future wife and in-laws looked on, Lopez led Schmidt to the middle of the snow-covered field.

“Joe, I’m going to let you tackle me and this is going to be your first tackle at Notre Dame Stadium,” said Lopez. “Your next tackle is going to be when you play here.”

“Really,” Schmidt said, “I’m going to play here?”

“Yeah!” said Lopez.

“That’s right, I’m going to play here,” said Schmidt, who then tackled Lopez.

The following year Schmidt made another pilgrimage to South Bend and again Lopez, now a junior, took him under his wing. This time he had Schmidt attend a world history class with him, seating the grade-schooler between himself and Anthony Fasano, the football team’s starting tight end.

Fasano handed Schmidt a pen and his notebook. “Here, Joe,” said Fasano. “Why don’t you take notes for me?”

Joe Schmidt was 11 years old. He still had not played his first game of organized football. However, when he returned home from this trek he jotted down three goals: 1) Play football at Notre Dame, 2) Be the fastest kid in the sixth grade and 3) Get good grades. Meanwhile, Lopez played every baseball game for the Irish with the words “Faith. Family. Baseball.” inscribed inside his baseball cap.

Schmidt was athletic and he came from a football family. His father, Joseph III, had played safety at the University of San Diego, while an uncle, Gary, had developed such a reputation as a high school linebacker that he earned the sobriquet “Head Ripper.”

Schmidt began playing tackle football at age 12 and would come to inhabit his uncle’s position. At Mater Dei, a perennial gridiron powerhouse, he would start three seasons at middle linebacker, collecting 98 tackles and being named team most valuable player as a senior. At a school that produced future USC quarterbacks Matt Barkley and Max Wittek during his four years, Schmidt was regarded as the team’s most diligent player and one of its best. However, at 6-foot and approximately 225 pounds, he was not a prospect that Notre Dame saw fit to offer a football scholarship.

“Joe was definitely frustrated,” says Lopez, who by this time had graduated medical school at the University of Texas–San Antonio and wed Catherine. During Schmidt’s senior year of high school the couple moved in with the Schmidt family in the town of Orange, California, as Lopez was just beginning an orthopaedics residency at the University of California, Irvine.

“Joe and I spent a lot of time together that year, his senior year of high school,” Lopez says. “He was fanatical about muscle-building and his diet, doing everything he could to get Notre Dame to notice him.”

“He’d ask, ‘Dad, what else can I do?’” says Joseph Schmidt. “It was heartbreaking because he wanted it so badly. I said, ‘Let’s start working on Plan B.’”

Other schools, including Air Force, Cincinnati, Miami and Arizona, offered Schmidt full scholarships. So did a few of the Ivy League schools, and one night a recruiter from the University of Pennsylvania attempted to clarify Schmidt’s choices for him.

“If you come to our school, you’re going to be a four-year starter, a team captain and all-Ivy,” the recruiter told Schmidt and his parents, Joseph and Debra, noting as well that financial assistance would make it tantamount to being on scholarship. “If you go to Notre Dame, you’re never going to see the field.”

And you’re going to pay your own way.

“That definitely made Joe mad,” Lopez says.

“As soon as that coach walked out the door,” the older Schmidt says, “Schmidt said, ‘That’s it. I’m going to prove him wrong. Nothing against you, Dad, but I don’t want to get to your age and wonder if I could’ve realized my dream if I had just taken the risk.’”

Lopez and Catherine, who had just named Schmidt to be godfather to their oldest son, Rocco, wondered what they could do to help. With everyone living under the same roof, Schmidt’s frustration was palpable. Then Lopez remembered that, after all, he and his wife were former varsity athletes at Notre Dame and perhaps their opinions mattered. Without informing Schmidt, Lopez wrote a letter to the Fighting Irish football coaching staff.

“This is an incredible kid,” Lopez wrote in part in an email. “His whole dream is to go to Notre Dame. You’re making a mistake if you don’t take a long, hard look at him.”

Meanwhile, Lopez was advising his little “brother.” “I told him, ‘Joe, wherever you go, you can do it,’” says Lopez. ‘You’re good enough and you’re smart enough. It’s going to be hard if you wind up at Notre Dame, but I know you can do it. Just make sure you don’t have any regrets.’”

Eventually, perhaps due in part to Lopez’s email, Notre Dame offered Schmidt a spot in the 2011 freshman class and a position on the team as a “preferred walk-on.” That meant Schmidt would be welcome to start fall camp in early August when the scholarship players would, but that there would be no financial assistance.

Still, even on his graduation day from Mater Dei, Schmidt wasn’t certain as to whether he should accept Notre Dame’s offer or a scholarship from Arizona or one of the other schools. As Schmidt exited the ceremony, his head coach at Mater Dei, Bruce Rollinson, himself a former defensive back at USC, stopped him.

“Coach Rollinson looked me in the eye,” says Schmidt, “he shook my hand, and he said, ‘You gotta go to Notre Dame.’”

And so Joe Schmidt left Orange County for Notre Dame and its lake-effect snow winters to pursue his dream. Two years later, he was summoned to Fighting Irish head coach Brian Kelly’s office to be told that he was being put on full scholarship.

“That was my first and remains my only one-on-one meeting with coach Kelly in his office,” says Schmidt.

One year after that Schmidt, academically a senior majoring in business with a 3.5 grade-point average but still a junior in terms of eligibility, was in the starting lineup for Notre Dame’s 2014 home opener against Rice. On that day Schmidt’s parents and siblings, his brother included, were inside Notre Dame Stadium again. This time Schmidt sent them a text message from inside the locker room: “All of my dreams are about to come true.”

Meanwhile, the brotherhood between Lopez, 30, and Schmidt, grows closer.

“They’re very funny together,” says Catherine. “Every Christmas Greg and Joe pick out two identical outfits and they do the old ‘Wild and Crazy Guys’ bit from Saturday Night Live.”

In 2015 Schmidt has the option to return to Notre Dame as a graduate student and enjoy one final season of eligibility. He still keeps a list of goals above his desk and since two of them are “All-American” and “team captain” and none of them are yet “play in NFL,” he most likely will. Lopez, meanwhile, has an opportunity to do a one-year orthopaedics fellowship in Chicago, so it is very likely that he, Catherine and their three young children will be returning to the Midwest.

“Won’t that be something if we live that close to Notre Dame for Joe’s final season?” asks Lopez.

It certainly would.

Joe Schmidt might even be able to pull some strings to get his brother onto the field.