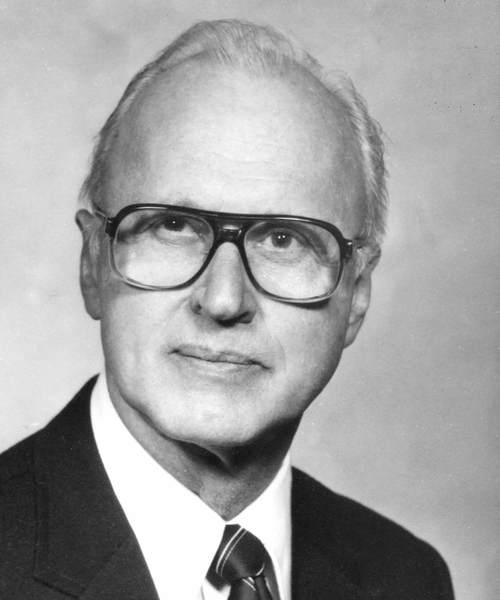

Les Bodnar

He cared for all the Irish

Time waiteth not. Even now it is wasting. And when you know the time is limited, and the supply of it is getting lower, it does cause one to look toward the finale. It may not be too far off. At 98, I probably don’t have much farther to go. I hope I did it right.

Four months after these words were published as the conclusion of his book, their author, Dr. Les Bodnar, turned the final page of his life.

From 1949 to 1985, Bodnar served the University of Notre Dame first as orthopaedic consultant and team doctor for football, then as director of sports medicine. His tenure with Fighting Irish athletics spanned the reigns of seven head football coaches, three athletic directors and two University presidents.

Orthopaedic surgeons were only just beginning to gain respect as experts in the total musculoskeletal functioning of athletes when Bodnar joined the staff of the athletics department at Notre Dame.

“Coaches in the late ’40s and early ’50s wanted their boys to play, even if it was not medically advisable on account of the possibility of jeopardizing an athlete’s long-term viability or health,” wrote Bodnar in “Notre Dame, Sports Medicine.” “I was eager to cooperate but not to the extent that I was willing to compromise the athlete’s welfare.”

Bodnar yielded neither to the intimidation of legendary football coaches nor to the skepticism surrounding his erstwhile nascent professional clout.

“There were lots of things that doctors didn’t know back then, but the important thing is that they cared,” said Dr. Fred Ferlic, who was Bodnar’s orthopaedic surgery protégé before eventually succeeding his mentor as chief surgeon in their shared private practice.

“Bodnar especially worked tirelessly to find new ways of treating injuries and helping athletes stay healthier longer. He was the Bill Gates and Steve Jobs of sports medicine. He knew the status quo was not good enough so he wanted to come up with better techniques and different solutions to orthopaedic issues.”

Ferlic recalls how a single, significant minute with former head football coach Frank Leahy and then executive vice president Rev. Edmund P. Joyce, C.S.C., shifted the entire culture of Notre Dame sports medicine.

“In the beginning, if Leahy didn’t like Les’ opinion, he’d consult a chiropractor in Chicago who would overturn it. Les didn’t think that was right so he made an appointment with Father Joyce, who wisely invited Leahy to that meeting.

“Joyce asked Leahy to describe his job: ‘What do you do, Frank?’ And Frank said, ‘I’m the football coach at Notre Dame. You know that, Father, you hired me!’ Joyce asked Bodnar the same question: ‘What is it you do, Les?’ And Bodnar said, ‘I’m an orthopaedic surgeon. I treat injured patients and students.’

“Joyce looked at Leahy and said, ‘You will coach football.’ He looked at Bodnar and said, ‘You will treat injuries. This discussion is over.’ It was exactly one minute in length. They were both excused and that was the end of it. That’s how principled Father Joyce was, and Father Hesburgh as well, so there was never any more inconsistency or wiggle room on that.”

The Fighting Irish won a national football title in 1949, Bodnar’s first year with Notre Dame athletics. Coincidence? Luck? Maybe just doing things right.

By the days of the Ara Parseghian era (1964–74), both Bodnar and his profession had earned recognition and a reputation for expertise. Highly regarded former head football coach Parseghian himself explains.

“One of the most important things for a football team is to have adequate medical attention—the game is rough and injuries occur. In all my years of coaching, the important decisions on the sideline with any injury always went directly to the doctor. Bodnar had supreme authority over the entire Notre Dame squad. If a player was not able to return to the game, then that was that. Under no circumstances was there going to be any jeopardizing of the long-term health and wellness of an 18- to 23-year-old athlete.

“We did it the right way,” Parseghian recalls, of the 11 years he and Bodnar shared responsibility for Notre Dame football. “We turned the program around in our first year (1964) together, with no violation of rules, no NCAA penalties, no purchasing of athletes. That’s something I’m very proud of. This was during a time in which there were a lot of shenanigans going on around the country as far as recruiting was concerned.

“We had a very energetic student body at that time, which was known for chanting ‘Ara, stop the rain! Ara, stop the snow!’ Hell, I couldn’t even stop the fumbles, let alone the rain and snow! Under any circumstance, Bodnar appreciated my total cooperation, and I appreciated his work.

“Les became a personal friend in a bond that was cemented across years. We had mutual respect and that kind of relationship is pretty hard to unlock,” says the coaching legend, with marked admiration for his former colleague.

A native of Chicago, Bodnar earned his bachelor of science degree from the University of Illinois in 1939 and graduated from medical school there two years later. Charity Hospital in New Orleans was the site of both his medical internship (1941–42) and surgical orthopaedic residency (1942–43; 1946–47).

In the middle of his residency (1943–46), his wife, Bunny, was pregnant with their first child. Bodnar was called to serve in World War II. As an orthopaedic surgeon for the U.S. Army both in England and France, he gained experience treating traumatic injuries and making judgment calls relative to the advisability of soldiers returning to the fight.

Ferlic remembers how Bodnar shared stories of the emotional difficulties he experienced while working for six months at a deserters’ hospital just before the Battle of the Bulge.

“Lots of these guys deserted because they were scared,” said Ferlic. “They were watching their buddies dying up on the front lines. They knew Patton was coming and knew how he dealt with deserters. Bodnar was surgeon and therapist both, which probably also served him well in his later dealings with student-athletes and their struggles.”

Bodnar’s firstborn, Thomas, was already 2 years old before he met his father, but it was illness that separated the recently reunited family again shortly thereafter. Within just a few months of coming home from the war, Bodnar found out he had tuberculosis and was quarantined in a Louisiana ward for half a year.

Upon completion of his residency, Bodnar established a private practice of orthopaedic surgery in 1947 that evolved into what is now known as the South Bend Orthopaedic Surgery and Sports Medicine Clinic (SBO).

“The first thing I noticed was his complete dedication to service of other people and service to the science of medicine,” recounts Ferlic, who came to South Bend in 1979 to join Bodnar at SBO. “If something didn’t go right in surgery, he stayed until it was right. If a screw wasn’t working the right way he’d pull it out and put in another one and stay in surgery until everything was as it should be, regardless of the time it took. I had enough admiration for him that even after he retired from practice in the late ’90s, I still consulted with him and he assisted me in many surgeries because I trusted and valued his input.”

As Ferlic recalls, “Les would get up about 5 a.m. or 5:30 a.m., do surgeries in the morning and hold office hours in the afternoon and evening, till about 10 o’clock at night. He used to go to conferences and present things and then come back here. He always scheduled surgeries for Sundays after the football team returned from games. The joke is, how did he and Bunny have nine children?”

Fortunately they did, because without the youngest Bodnar, there might never have been a 1979 Notre Dame Cotton Bowl victory.

Although frequently recognized as one of college football’s most legendary games, featuring one of the most renowned pieces of Fighting Irish lore, likely few of its expert historians are aware that it was Beth Bodnar who made the whole thing possible.

“It’s known as the chicken noodle soup game, but years later Dad insisted it had been just plain noodle soup,” she laughs. “I was down in Houston with my parents for the game and the weather was just horrible, the worst storm they’d had in decades. Dad was always a wimp about cold, and I didn’t know how he was ever going to survive the ice and sleet and wind, standing on the field the whole time. I had brought some soup packets for our hotel room and I suggested he put a couple in his coat pocket to heat up during the game. As a little girl, I offered my best solution.”

A hypothermic Joe Montana ended up eating that soup, recovering sufficiently to bring the Fighting Irish to a miraculous last-minute one-point victory over the Cougars and earning his own spot in the annals as the Comeback Kid.

“My father loved Joe very much,” Beth remembers. “They kept in contact long after Joe graduated from Notre Dame.”

Following his own departure in 1985 from official University responsibilities, Bodnar maintained his private practice at SBO, setting ever-higher standards in an orthopaedic surgery career lasting 52 years. Upon retirement, he continued to work as a consultant to Ferlic at SBO and with clinics serving indigent and migrant populations.

Bodnar was a founding member of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine and a fellow of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, the American College of Surgeons and the American College of Sports Medicine, among other professional memberships. For six decades, he conducted national sports medicine conferences for coaches and athletic trainers, giving seminal presentations that established precedent and practice for the field of orthopaedic surgery. Consistently hailed as one of the best, he was regarded as much for his innovation and contributions as for his integrity and discipline.

Early last winter, 98-year-old Bodnar fell and broke his hip. His hospitalization and medical care were carried out by none other than Ferlic. “It had only been a few days after surgery when he told me he was going home,” Ferlic shares.

“I told him, ‘No, you can’t do that, you need to be in a nursing facility.’ And he said, ‘I’ve already broken one hip, I’ll break the other one next week, and this is pretty much the end. I want to be at home.’ He was 100 percent mentally capable, but knew his body was failing him. I consented to release him from the hospital.”

Rev. Paul Doyle, C.S.C., a rector on campus and one of the priests who cared for former University president Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., had long since been in the habit of visiting with Bodnar and providing spiritual care, practices he continued after Bodnar returned home.

“The thing about Father Doyle,” Ferlic discloses playfully, “is that he is perpetually late, has never been on time for a single thing in his life. He had already administered last rites, but he promised Les he would come back again the following evening at 5 o’clock.”

Father Doyle arrived at 4:40 p.m. on Dec. 16, 2014, and anointed Bodnar, who died at 4:45 p.m., surrounded by family and loved ones.

So, even at the end, Les Bodnar did it right.