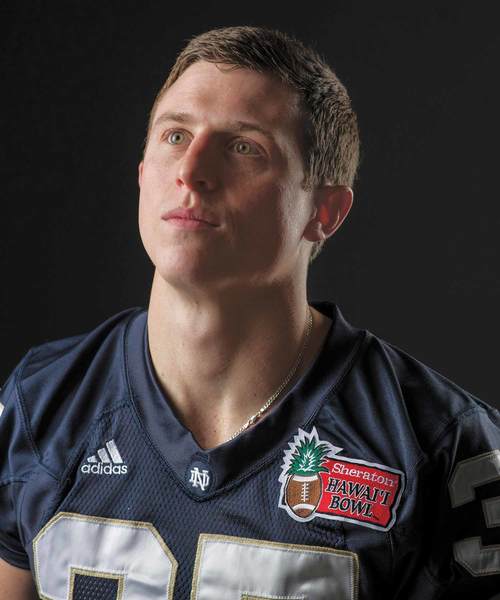

Mike Anello

Taking St. Baldrick’s to Boston

When former University of Notre Dame football player Mike Anello couldn’t find a charity in Boston that made him feel as passionate as his work for children’s cancer at Notre Dame, he decided to create his own St. Baldrick’s chapter.

Others said it would be difficult, that there were too many obstacles to overcome. There was no structure in place or name recognition for St. Baldrick’s, and there was already a well-established Jimmy Fund for children’s cancer in Boston. And who wanted to shave their head?

Anello savored the familiar tingle, the one that precedes the moment he proves the doubters wrong. Creating a nonprofit from scratch would be nowhere near as unlikely as an under-sized walk-on becoming a superstar special-teams torpedo on the country’s biggest football stage.

He recalled when Notre Dame’s defensive coordinator put together a video of him making about 10 plays on the scout team in spring football practice during his sophomore year. Coach Corwin Brown stopped the video and addressed all the defensive players.

“I don’t want to hear that this kid is 5-foot nothing or 100 and nothing or a walk-on,” Brown said. “This kid is going to play before he leaves here because every time I turn around, he’s making a play in practice. I promise he will play on Saturdays.”

If that scene seems like it’s straight out of a walk-on’s fantasy or a Hollywood movie, that’s because it echoes a line from the beloved 1993 underdog film Rudy. Except that Brown’s prediction was right, and Anello succeeded in a way Rudy didn’t even dream.

Anello made 23 special-teams tackles in 72 opportunities in his senior year at Notre Dame. Making nearly one out of three chances despite being one of 11 players attempting the tackle takes talent, but it’s also a testament to the power of determination.

He was so effective in his first game against USC as a junior—making tackles and drawing penalties on punt coverage—that Trojan coach Pete Carroll shouted at his team: “How the hell aren’t we going to stop this little kid? He’s four feet tall.” By the next year, Carroll game-planned specifically to stop Anello.

As a newly minted graduate working at a venture capital firm in Boston, Anello channeled the same passion that stymied would-be blockers into his business career and service work. The success of his St. Baldrick’s chapter—raising about $150,000 in its first three years—is not surprising considering his history of using guts and effort to prevail what though the odds.

“His career, it’s nothing short of amazing,” said Terrail Lambert, a scholarship player who had the best seat for Anello’s rise from walk-on to special-teams star. “He’s 5-foot-8, but if you judged him by his character, he’d be taller than all of us.”

Anello grew up in Rudy country, the south suburbs of Chicago. In fact, he wrestled regularly against Rudy’s nephew, Dan Ruettiger. Anello credits his father, a sales representative, for his dogged determination. He said his mother, a high school attendance secretary, taught him a passion for helping others.

At Carl Sandburg High School, he took up wrestling because a brother five years older wrestled. That brother also started at center on the football team despite weighing, at 150 pounds, less than the quarterback. The youngest Anello played football as a sophomore, and the coach said he would play more if only he were taller and heavier.

He focused on wrestling as a junior and would later take third place in his weight class on a state championship team. The varsity football coach asked him to try out again senior year, and he won a starting cornerback position and was regularly elected captain by his teammates.

Anello considered wrestling at the University of Illinois. But a visit to Notre Dame led to a chance meeting with a janitor in Dillon Hall. It was only a few minutes, but he was impressed that there was clearly a level of respect between the students and janitor, that they talked easily. “Most places, kids don’t care,” he said. “I thought it must be a really special place.”

In the spring of his freshman year, Anello decided to try out as a walk-on, figuring he would at least stay in shape if he made it. About halfway through the next fall season, he overcame some injuries and started to make plays in special-teams practice.

Coach Brown’s highlight video and promise of playing time provided motivation, showing that all the hard work would not be in vain. Still, Brown asked for some high-school clips because some coaches still questioned whether Anello could perform under pressure. Anello had to create a highlight film because he didn’t have one.

The next step was to convince Irish head coach Charlie Weis, who was reluctant to take such a risk when he had world-class scholarship athletes on his roster.

That summer, Anello lived with his brother in Chicago, working 80- to 100-hour weeks at an investment banking internship. Not wanting to regret giving his best shot at getting on the field, he declined his acceptance to study in Italy during the spring semester of his junior year. He spent the few hours not working doing extra running.

“I kept in touch with the scholarship guys at school,” Anello said. “If they were doing 12 sets of 110-meter sprints with 16-second rests, I would try to do 14 sets with 14-second rests. I knew I had to work that much harder than them to work my way onto the field.”

The gunner’s job on punt coverage is to line up wide, beat a blocker downfield, and tackle the punt returner before he can start his return. Blockers like Lambert encouraged Anello in fall practice, telling him he was better than most of the starting gunners on other teams.

“I was in awe of him because he put himself through all that misery when he could get into Notre Dame on his academics,” Lambert said. “I became a fan.”

While pleased to see his name on the bottom of the depth chart, Anello never believed he’d play. Preparing for the Michigan game, he was asked to play the scout-team part of a gunner Notre Dame planned to double team. He consistently made the tackle anyway.

“After the third time in a row, I heard Coach Weis yell, ‘Where the hell is Anello?’” he recalled. “I was worried about what I did wrong. Coach said, ‘Get back on that line, you’re going to Michigan.’”

When he saw his name atop the depth chart at gunner the next day, he figured Weis was using him to motivate others. “I stared at it for a few minutes because I couldn’t believe it,” he said. “I still get chills thinking about it.”

He told his family to attend the game. The first time Notre Dame had to punt, he ran on the field first so the coaches couldn’t change their minds. He made a tackle on the second punt, marveling that his name would really be in the record books.

Before the next game, the equipment manager told Anello he was getting a new number. He was excited because it meant the coaches planned to keep playing him. His new jersey was number 45, Rudy’s number. Anello asked Weis if it was a joke and got a smirk in reply. Recognition built slowly. The announcers didn’t know his name early on because his number change wasn’t in the program. Several times, he was told he couldn’t enter locker rooms because they were only for team members. He simply didn’t look like a football player.

His efforts on the field, though, couldn’t be overlooked. Against USC, he drew one penalty by using a wrestling move, grabbing his blocker and flipping over the top. Anello was so successful on the punt team that Weis put him on kickoffs, too. He was awarded a scholarship and new number for his senior year.

Anello credited the coaches with putting him in position to have as many tackles as he did his senior year. He had incredible highlights, such as recovering a fumble and causing two against Michigan. He seemed to be all over the field on special teams, and the media loved the Rudy angle. Fittingly, the guy who gave everything he had broke his leg in the season’s last game.

But when he later told his story in a video blog to raise money for St. Baldrick’s, he didn’t brag about his senior heroics. He focused on the walk-on journey it took to get there.

Catherine Soler was a student government leader who helped start St. Baldrick’s at Notre Dame and recruited Anello to build its campus recognition.

“Mike said he wanted to get more involved in our second year,” she said. “He got the athletes involved and rallied everyone around him to the cause. It’s great to see a student-athlete use his prominence to motivate others and be a role model.”

Anello later called Soler for advice on how to start his own St. Baldrick’s chapter in Boston. He built the event to include triathlon sponsorships and other fundraisers, reaching out to Notre Dame alumni living in Boston and former teammates around the country. (Anello recently moved to Portland, Oregon, as director at business development for Axiom.)

“I wasn’t surprised,” Soler said. “He’s so competitive. Mike is a high performer in every aspect of his life. He’ll be successful at anything he does.”