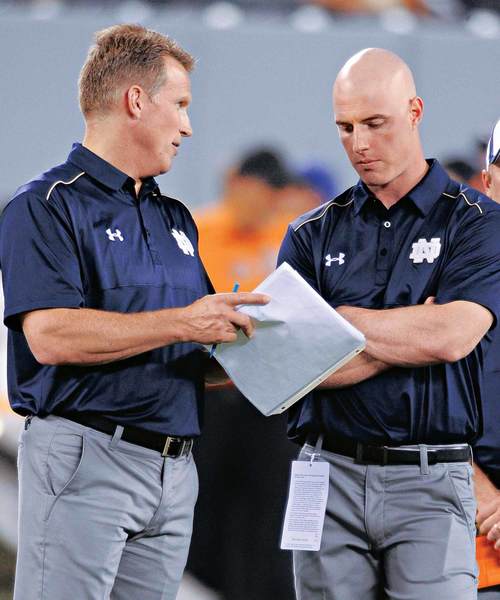

Pat Eilers & Kyle McCarthy

An unlikely tandem

If cornerbacks reside “on an island,” whither safeties? Do they exist on a precipice?

Safety, as the name implies, is the last line of defense on the gridiron. It can be the loneliest and most precarious of positions on the football field, particularly when a freight train in shoulder pads rumbles head-on at you in fourth gear. When you line up eight to 12 yards beyond the line of scrimmage, literally no one has your back.

Except, perhaps, another safety.

During the 2014 football season, the job of coaching University of Notre Dame safeties fell to a pair of former Fighting Irish safeties. Both men, first-year graduate assistant Kyle McCarthy, 28, and designated “next man in” Pat Eilers, 48, undertook journeys that neither ever foresaw when the calendar turned from July to August.

McCarthy, a former Fighting Irish team captain, embarked on a battle against cancer. Eilers, an erstwhile flanker and safety who started on Notre Dame’s 1988 national championship team, took a sabbatical from a highly respected position in private equity to become an unpaid underling on Irish head coach Brian Kelly’s staff.

“Totally surreal,” Eilers recalled in the midst of Notre Dame’s 2014 season. “On a Thursday morning in August I was in my office in Chicago and 24 hours later I was sitting in a staff meeting in the Gug (Guglielmino Athletics Complex).”

“I’ve sat in my chemo treatments thinking, ‘What the heck am I doing here?’” said McCarthy. “I’m 30 years younger than most people in here and a year ago I was playing in the NFL.”

Their odyssey began on the first day of August, as Notre Dame’s football staff herded themselves over to Kelly’s home for a cookout. It was a Friday, just two days before the team would embark on a week-long pilgrimage to the Culver Academies to commence fall practice. This communion was, in a sense, the coaches’ and support staff’s last carefree whiff of summer.

Outside on Kelly’s driveway McCarthy attempted to absorb a piece of very worrisome news. Less than a year removed from a four-year NFL career truncated by four surgeries on his right knee, McCarthy clutched his cellphone. On the other end of the call a doctor informed him the tests of his testicular cancer screening had come back positive. He was scheduled for surgery the following day to have a testicle removed.

“It was the beginning of a roller-coaster few months,” says McCarthy, who in 2008, his first season as a starting safety for the Irish, set a single-season school record for tackles by a defensive back (110). “Nothing really prepares you for that moment.”

The procedure, known as an inguinal orchiectomy, was performed that Saturday. Two days later, when the Irish convened for their initial practice of the 2014 season at Culver, McCarthy was on the field, coaching the safeties. Only the coaching staff was aware the surgery the newbie coach had undergone.

And there the episode might have ended except that a week or so later McCarthy was informed that his cancer was in Stage 3. It had spread to his lymph nodes and to one of his lungs. He would need to begin four rounds of chemotherapy immediately.

On Aug. 15, two Fridays after McCarthy had stood on Kelly’s driveway, the Chicago Tribune reported that the Youngstown, Ohio, native would be taking a leave of absence (though he would not) from coaching and that he had a “very treatable form of cancer.”

Eilers, a managing director at the Chicago-based private equity firm of Madison Dearborn Partners (MDP), read the article with deep concern. Exactly 20 years before McCarthy was a two-year starter for the Irish in 2008–09, Eilers had been a two-year starter in 1988–89. Though Eilers had started mostly at flanker for coach Lou Holtz, he had played some safety and gone on to a six-year NFL career at that position with the Vikings, Redskins and Bears.

“I knew Kyle had played in the NFL,” says Eilers, who in 1988 had scored Notre Dame’s decisive touchdown in the classic 31-30 defeat of top-ranked Miami. “All the Notre Dame NFL safeties know each other. When one of us is in need, we see if we can help.”

Eilers immediately placed a call to Chad Klunder, Notre Dame’s associate athletics director for football operations. A friend of Eilers, Casey Newell, had played basketball for the Fighting Irish and also had gone on to a career in finance in Chicago. Newell had beaten testicular cancer in the 1990s. Eilers gave Klunder Newell’s contact information, the name of the chair of the urology department at Northwestern who had treated Newell and recommended that McCarthy phone both of them.

“Please let Kyle know I’d be happy to speak to him as well,” Eilers told Klunder, “and let me know if there is anything else I can do.”

Klunder cracked a joke—or was it?—in response.

“Yeah, there is something,” quipped Klunder. “You want to come down and help coach?”

The thought hadn’t crossed Eilers’ mind. However, even though he knew Klunder was joking, he said, “If you thought I could help the Notre Dame football program and Kyle, please let me know.”

At that moment Klunder realized Eilers was serious. So he walked the idea down the hall to Kelly, who loved it. “I think it’s a great idea,” Kelly told Klunder. “Do you think he’s serious?”

The following Monday Eilers received a text from Klunder stating he was working on it. On Wednesday, Notre Dame received an exemption from the NCAA to bring another person on staff, given McCarthy’s situation. Klunder contacted Eilers and stated, “We think you are the best solution given the unique circumstance, if you are serious about doing this.”

That evening, Eilers, a married father of four who lives in Winnetka, Illinois, huddled with his family. His two older daughters, Elizabeth and Katherine, had just embarked on their senior and sophomore years, respectively, at Notre Dame. Katherine is a member of the women’s lacrosse team. His wife Jana, their daughter Clare and their son Patrick discussed the possibility.

“They were excited given they are all athletes and Notre Dame fans,” Eilers said. “But we also discussed my being away. Given the younger kids’ older sisters were at Notre Dame, we all knew there would be a few football weekends when we all would be together.”

Eilers solicited the advice of former Irish teammate Andy Heck, one of his closest friends and now the offensive line coach for the Kansas City Chiefs. Heck posed just one question: “What does Jana think?” That, too, was Kelly’s and Klunder’s primary concern.

“I painted a realistic picture for Pat of the time demands it would take, wanting to make sure there would be no surprises,” Klunder says. “And I wanted to know I had Jana’s blessing, too.”

Jana Eilers was on board because she knew it was the right thing to do and she knew what a large component Notre Dame football has been in her husband’s life. She didn’t want to deny him the opportunity to give back in this unique way and she was willing to make the sacrifice. The following morning, Eilers spoke to his partners and they were on board with him coaching for the fall, while he continued to monitor his portfolio companies. He drove down to Notre Dame that Thursday afternoon and met with Kelly and Klunder. Within a week Eilers had taken a sabbatical from MDP and began working for first-year defensive coordinator Brian VanGorder. When Eilers, a square-jawed Minnesota native who is refreshingly direct, met Kelly, he was adamant. “I only want to do this if you really need me,” he said, “and if you think it’s the best thing for Notre Dame football.”

Even though Eilers was taking an unpaid position, he was required to fill out an online application for Notre Dame’s human resources department. That was an odd proposition for a man who oversees billions of dollars in energy and power sector investments for MDP and is also a member of the College of Engineering’s Advisory Council. A man of no pretension, Eilers filled out the application and, as he told Klunder, “I can make copies as well as anyone.”

Meanwhile, McCarthy’s trials did not abate. His grandfather, Jackie Mayo, a former captain of the Notre Dame baseball team who had also played in the 1950 World Series as a member of the Philadelphia Phillies’ renowned “Whiz Kids,” died at age 89. “My grandfather was my role model in all that he did,” says McCarthy, whose two brothers also graduated from Notre Dame (the younger of the two, Daniel, was a reserve defensive back for the Irish). “He’ll be remembered fondly.”

Eilers and McCarthy met briefly when the older alumnus arrived on campus, but McCarthy left soon after to attend Mayo’s funeral. McCarthy missed the team photo and when the players and coaches took their seats to pose inside Notre Dame Stadium, Eilers stood off to the side.

“I had just arrived and didn’t think it was right for me to be in it,” says Eilers, “but Kerry Cooks, our defensive backs coach, told me, ‘You’re part of the team. You have to be in the photo.’”

Through the season’s first eight games, McCarthy never missed a practice, even while enduring four separate rounds of chemotherapy treatments, each round consisting of five six-hour sessions.

“I made it very clear to Coach Kelly that I wanted to be on the field as much as I could,” says McCarthy. “I have a job to do. I signed up for it. I told Coach Kelly I would be there.”

The routine, if you could call it that, would consist of McCarthy undergoing chemo and then arriving at the Gug at around 2 p.m., an hour or two before practice. Cooks put McCarthy in charge of the safeties and, like any assistant coach, he was also given a geographical area to oversee in terms of recruiting.

“I have a recruiting area that never stops,” McCarthy said in the midst of a first season that might have been challenging enough without the chemo treatments. “My time has been eaten up.”

Meanwhile, Eilers usually arrived at 7 a.m. and undertook most of the administrative duties McCarthy would have been responsible for during those hours. During practice Eilers normally oversaw the scout team offense for the first-team defense. Afterward, he’d return to the Gug with the other coaches to break down offensive game film of the upcoming opponent.

“The quality of life for a coach during the football season isn’t spectacular,” Klunder says. “We wanted to make sure Pat knew what he was getting into. But I don’t think there’s never been a day where Pat wondered, ‘What am I doing here?’”

Eilers and McCarthy had more in common than even the two of them might have realized. While the younger man idolized his grandfather, the former Irish team captain, he may not have known Eilers had played on the Notre Dame baseball team in 1989, hitting .307 in 53 games.

Too, neither were overnight successes as Irish players. McCarthy was primarily a special teams player his first three years at Notre Dame and saw no game action as a freshman. Eilers transferred to Notre Dame from Yale after his freshman year and, after missing an assignment on a rushing play during the spring of his sophomore year, he incurred the wrath of Holtz.

“Coach Holtz stopped practice, ran over to me and said that perhaps I should have stayed at Yale,” Eilers recalls. “I yelled back at him that I did not transfer from Yale to not play.”

Holtz, a bit surprised, ordered the play to be run again. This time Eilers made the stop.

The 2014 season should have been a most turbulent autumn for Notre Dame’s secondary. If a first-year grad assistant undergoing chemotherapy while serving under a first-year defensive coordinator was not enough of a quagmire, Irish safeties were dropping like October leaves on the North Quad. Senior Austin Collinsworth, a team captain, missed the season’s first four games and then tore his labrum early in the sixth and was lost until the Northwestern contest. Nicky Baratti, a junior, dislocated his shoulder in the third game and was lost for the season. Eilar Hardy, another upperclassman, sat out the first two months.

After the season’s third game against Purdue, a game in which Notre Dame’s other starting safety, Max Redfield, was ejected for targeting, Eilers told VanGorder, “Coach, we are running on fumes at safety.”

McCarthy, of course, knew that feeling, but rarely shared it with anyone. The nausea. The metallic taste in his mouth. The increased sensitivity in his outer appendages. The weight loss.

“I got a new haircut,” McCarthy would say while noting that Redfield had dubbed him “Smeagol” after the hairless creature from The Lord of the Rings trilogy. Kyle’s mother, Janet, who is also Jackie Mayo’s daughter, always visited South Bend during the worst weeks to help care for her son.

“My mom is an amazing woman,” says McCarthy.

“There are days you wouldn’t know Kyle’s in chemo,” says Klunder. “Other days he looks tired, but he’s a tough sonofagun. Kyle’s heart is Notre Dame. It’s where he is destined to be.”

“I want to tell everyone to stop worrying about me, I’m going to be fine,” McCarthy says. “Still, I have made some time to make a few trips to the Grotto, more so than I probably would have.”

On the last Monday night of October, McCarthy headed south to Indianapolis, to the same medical center that once treated Lance Armstrong’s testicular cancer (and Casey Newell’s), to learn the results of his latest tests. The following morning he was informed that what doctors first believed to be scar tissue was indeed more cancer. It would need to be removed within the week.

And because that surgery would be more invasive, McCarthy finally would be forced to miss a practice. In fact, he would miss at least a few weeks.

Back in South Bend, Eilers stopped by Klunder’s office, coaching the situation.

“We need to send flowers to Kyle’s mom,” Eilers told Klunder, “because she’s going to take this news hard. Do you want to use my credit card?”

Klunder smiled, told Eilers the flowers were an excellent idea and surmised that the Notre Dame football program might be able to raid the petty cash jar to pay for them. Still, Klunder marveled at a man who had spent about five nights in his own bed the previous two months, working long hours pro bono, still putting others first. In fact, on Notre Dame’s two bye weekends, Eilers had flown off to Boston and Tulsa to attend MDP portfolio company board meetings, which conveniently fell on the two weeks the team wasn’t playing.

“This isn’t about me, I’m the lowest man on the totem pole here,” says Eilers. “Everybody has varying amounts of time, talent and treasure that they can give. Treasure is easy to give if you have it. This was an opportunity for me to give my talent and my time. Anyone in my position would do this because Notre Dame had such an impact on my life.”

As for McCarthy, as he was recovering from a second surgery sandwiched around two dozen or so chemotherapy treatments, his voice was resilient.

“All of this definitely caught me off guard,” he said.

“Sometimes God has other plans for you and I didn’t have much of a choice here.

“But it’s a fight I’m going to win.”

On Nov. 13, McCarthy returned to meetings and told Irish coaches that, according to his doctors, he is cancer free.