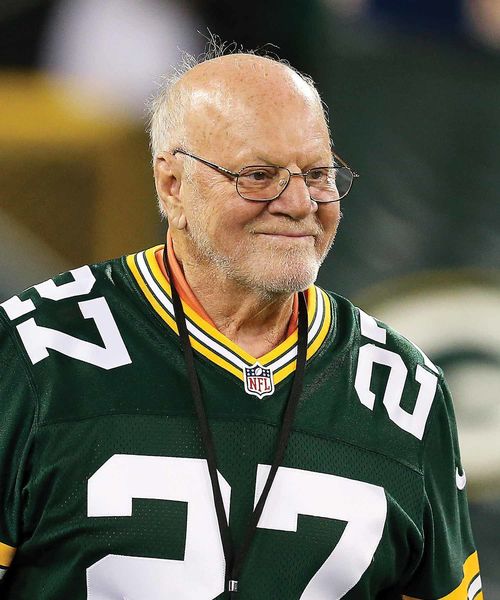

Red Mack

A Football Life—and Much More

Maybe the toughest person that William “Red” Mack faced during his football beginnings wore a habit, not a helmet.

“Sister Madeline,” Red remembers. “She grabbed me by the back of the neck and told me to go get a football uniform. She said for me to put my bad temper to good use.”

He did. Long before he suited up for the University of Notre Dame and the Green Bay Packers, Mack was a star running back at St. Paul’s Orphanage in his hometown of Pittsburgh.

“And if I didn’t play well, Sister Madeline would let me know about it.”

He pauses. “The orphanage—best thing that ever happened to me. I had a nun for a mother and the discipline that I needed.”

Mack and his four younger siblings ended up at St. Paul’s when he was 10 years old. When their parents separated, neither one of them wanted to raise their children.

By then, Mack was two years behind in school. He was frequently absent because his parents were often indisposed and he would stay home to take care of his siblings.

He still found time for games and grapples.

“I grew up on the north side of Pittsburgh and you fought when you lost and you fought when you won,” he says. “I got my nickname of Red because I had carrot red hair and there was a little saying that went with it that I didn’t like.

“That was why football was so good for a guy like me with a bad temper. I had a great way to channel it.”

Football became his salvation. It kept him in school, earned him a scholarship to Notre Dame and gave him a chance to play six years in the National Football League—his last game coming in the first Super Bowl where he made the tackle on the opening kickoff.

Mack, now 80, admits he had a lot of help rising above his humble and hardscrabble beginnings.

“There always seemed to be someone there to give me a hand,” he says.

—At St. Paul’s, he had Sister Madeline and his football coach, a crippled man named George Palooka, who also had grown up in the orphanage.

—Then after four years at the orphanage, his maternal grandparents took over the care of Mack and his siblings. Mack went to Hampton High School, where he starred in football for his coach, Chuck Fay.

“He was like a father figure to me,” Mack says. “We became so close that I later served as the best man at his wedding.”

—At Notre Dame where he struggled academically as a freshman, he had assistant coaches Hugh Devore and Bernie Crimmins stopping by his room almost daily to check on his progress.

“Bernie would sometimes just sit there while I studied to make sure I did it,” Mack says.

“If I hadn’t had football and my coaches, I figure I would probably be in jail right now,” he admits.

“Jail?” his wife Jean questions. “Actually, I think he would probably be dead without football.”

Jean has always been a soothing influence, helping keep any of her husband’s demons from the past well below the surface. Around the home, she’s the boss.

“Until a couple of years ago, I never even had a cell phone or a credit card,” Mack admits. “I’ve still never written a check. Jean takes care of all that.”

They met at The Volcano hangout in downtown South Bend during Mack’s senior year.

“I asked who the pretty blonde was with the nice knees” he recalls. Jean Burkhart was her name and Mack found that she really didn’t give a hoot about Notre Dame football back then even though her dad did.

“I let him chase me for six weeks before I went out with him,” Jean recalls.

They have been married 55 years. After Mack’s pro career, they returned to her hometown of South Bend to raise their three boys. Red was hired as a supervisor at Bendix and worked there for more than 35 years.

But back to Mack’s Notre Dame career.

In 1957, he joined head coach Terry Brennan’s team as a 165-pound running back. He started as a sophomore in a backfield that included Bob Williams at quarterback and Nick Pietrosante at fullback. He gained more than 500 yards that season.

During his junior and senior years, he was limited by injuries but was always appreciated by the fans for his gutsy, all-out play. When he returned to the sidelines as a senior after an injury ended his season, he received a standing ovation from the crowd.

“The Notre Dame student body never forgets,” he says. “They are the best in the country, bar none.”

A little guy as tough as nails, Mack also was respected—and maybe a little feared—by his Irish teammates. He set the tone for his play early in his freshman year when his two front teeth were knocked out by a forearm from All-America end Monty Stickles. He was back the next day and told Stickles, “Don’t you ever turn your back on me, you big SOB.”

Mack meant it. Six years later when he was playing for the Pittsburgh Steelers, he saw a familiar figure coming down the field on a kickoff. It was Stickles, playing for the San Francisco 49ers.

“I made a right-hand turn and blindsided him. Then I stood over him and said, ‘I finally got you back.’”

Mack had joined the Steelers after graduating from Notre Dame in 1961. He was up to 175 pounds by then and was drafted to play wide receiver.

“I thought they drafted me out of kindness because I was a hometown boy,” he admits.

“But Chuck Fay (his old high school coach) gave me the confidence that I could make it and told me not to take anything from anyone on the field during training camp. There wasn’t a defensive back on the field I didn’t have a fight with. When they pushed me, I pushed back. When they hit me, I really went after them.”

Mack was later told by Pittsburgh quarterback Bobby Layne that the coach, Buddy Parker, was enthralled with Red’s toughness and how he never knew what Red was going to do from one day to the next.

He stayed with the Steelers for three years as a spot starter and member of the special teams and then spent a year with the Philadelphia Eagles before returning to the Steelers for one more season in 1965. Atlanta then picked him in the expansion draft only to cut him.

Mack went back to South Bend with Jean, ready to retire.

“That following Tuesday, Jean woke me up and said Green Bay was on the phone. It was Vince Lombardi and he asked me when I could be there. I said, ‘The next practice,’ and I was there the next day.”

He loved that one year with the Packers—playing mainly on special teams and gaining the distinction of making the initial tackle in the first Super Bowl, a game that Green Bay won 35-10 over Kansas City.

“Lombardi treated everyone the same,” Mack says. “Paul Hornung might have been the best player in the NFL at the time, but I got treated just like him. When you did something right, you were told. When you did something wrong, you were told, too.’"

By the time Mack joined the Packers, he was playing with a lot of pain.

“I have a high threshold of pain,” he admits. ''I loved playing so much that I just tolerated it.’'

But when he was traded to Detroit the following season, he decided he had had enough. Nothing was ever going to beat that Super Bowl season with Green Bay and playing for Lombardi.

Mack went to work at Bendix as a product control supervisor. He tried his hand at coaching his boys in junior high, too.

“But when they got older and never had a fist fight, I told Jean I didn’t think any of them had the meanness I had to play football,” he says.

So they didn’t play. And that was fine with Mack, a member of both the Pennsylvania and Indiana football halls of fame. He knew he needed football to survive—he knew his sons didn’t.

Although he had a stent put in his heart four years ago and has undergone several replacement surgeries—including on both knees and hips and one of his shoulders—Red says he still gets around pretty well.

“All I know is that I trigger the alarms at the airport just by pulling into the parking lot with all that metal in me,” he says with a smile.

And the CTE brain disease that has affected many retired football players?

“It’s a concern,” he says. “But I don’t think it’s going to happen to me. I tackled with my arms and not my helmet.”

For the hard-hitting and hot-blooded competitor that he was once, Mack admits now that his competitive drive has worn off.

“I like to work out in the garden and in the yard and can’t wait when March rolls around and I can get out there again.”

Red and Jean also have accumulated about 3,500 hours of volunteer work at Healthwin, a senior retirement facility. That started when Jean's mother, Mary Burkhart, moved to Healthwin 14 years ago and it has continued after her death in 2010.

The Macks are there for the senior proms, special events and many meals. And it isn't unusual to see Red telling stories to residents and guests, bussing tables and pushing around wheelchairs.

“It’s such a joy to be there,” he says.

The Macks, members of Christ the King Catholic Church, also are mainstays at Healthwin's Sunday Mass.

“Red thinks he's the head usher," Jean says.

"They are like family out here," Healthwin volunteer coordinator Karen Martindale says.

Mack enjoys looking out for others. He says that enough people looked out for him.

“If I had to live my life over and I knew how it was going to turn out, I would do it just the same,” he says. “There may be a few different roads you can take, but I think God does have some sort of plan for you.”

“If we ever write a book on Red’s life, I think the title should be, ‘From the Orphanage to the Super Bowl,’” Jean says.

It’s been quite a journey—as football took over for the fistfights and then family and faith became even more important.

“Vince Lombardi always said if we loved our faith, our families and our jobs, then he would feel like he’d been successful,” Mack adds. “I would have liked to have told him that I accomplished that.”

And much more.