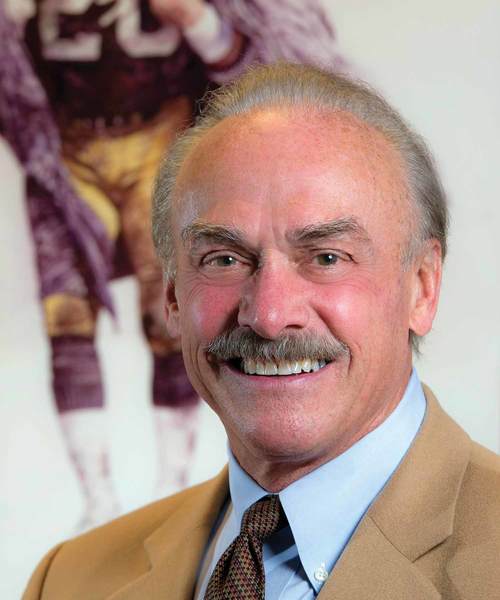

Rocky Bleier

From Vietnam to the Super Bowl

The Rocky Bleier story is one of the great sports stories of a generation, and it deserves retelling today. But to fully understand the Rocky Bleier story you need to remember how unpopular the Vietnam War was. It angered and divided the country, triggering its own wars at home.

Vietnam was the focal point of an escalating war to stop Communism in the mid-1960s, and antiwar passions were fueled by those susceptible to the military draft—males as young as 18—in the decades before the United States established an all-volunteer army. In 1965, college students marched, demonstrated and burned draft cards from Berkeley to the Pentagon. In 1967, 400,000 protestors marched through New York City. In 1968 the violent clash between 10,000 young people and 23,000 police officers startled a national television audience watching the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

In October 1969, millions of Americans skipped work to protest the war and a month later a half-million people participated in an antiwar demonstration in Washington, D.C. In the spring of 1970, four students were shot and killed during a protest at Kent State, and a week later 100,000 gathered in Washington, D.C., to oppose the shootings and U.S. incursions into Cambodia.

On May 4, more than four million students staged a strike to express their resistance to the war. At the University of Notre Dame, too, demonstrations took place that spring, draft cards were burned, the ROTC building vandalized and classes canceled, bringing the semester to an abrupt close.

While protesters took to the streets, others tried to avoid combat duty in Vietnam by enlisting with the Army Reserve or National Guard or declaring religious or moral opposition to the war and obtaining deferments as conscientious objectors.

This—and the raw combat airing nightly on network television and the demoralizing war itself, with all the human damage, the body bags and heartbreaking casualties as well as examples—certainly, of honor, sacrifice and courage—this was the backdrop for the Rocky Bleier story.

Robert Patrick Bleier, who got his nickname as a baby and grew up above his father’s bar in Appleton, Wis., was an undersized, overachieving halfback on Notre Dame’s 1966 national championship football team. He was the team captain in 1967, graduated from Notre Dame in 1968, and drafted by the Pittsburgh Steelers in the 16th round.

Bleier persevered with the Steelers through his rookie season but was drafted for a second time in 1968, this time by the U.S. Army. “It was 1968,” he would say years later. “It was the height of the war, we had 500,000 troops over in Vietnam and any warm body was going to be drafted. And so all the National Guard and reserve units were full.”

Seven months later Bleier was in Vietnam as a foot soldier with the 196th Light Infantry Brigade stationed in Hiep Douc. And while some 400,000 young people partied at an unruly festival of peace, love, drugs and music called Woodstock, Bleier was a world away, carrying a grenade launcher through the rice paddies of the Que San Valley. His mission that August—and that of two platoons from Company C—was to bring back the dead and wounded of Company B which had been ambushed and decimated by the North Vietnamese Army (NVA).

But things didn’t go as planned. The NVA was entrenched—deadly, ferocious, unseen but seemingly everywhere—and Company C walked into the firefight not knowing they were outmanned four to one. They battled through two bad days and a couple of brutal nights—before the story turns worse.

On the morning of Aug. 20, 1969, Bleier and a few others emerge from some woods into a clearing—dried-out rice paddies—when they come under fire from an NVA machine gun. They dive, and roll. Bleier tries to pull off his pack, struggles, gets it off, grabs his grenade launcher and crawls about 20 yards to get a bead on the machine gun. It is 40 yards away, in the bushes of a woodsy knoll. Bleier loads and … feels a dull thud in his left thigh. He’s hit.

He’s down, shot through the leg: no bone damage, but blood-gush from entry and exit wounds that include a four-inch swath of flesh blown out of his left thigh. The pain is searing. He is pinned down by enemy fire. Any bandages he carries are in his pack, in the open where he left it behind. Still, hoping to provide cover for others, he lobs a few rounds into the bushes where the automatic weapons’ fire is coming from. He considers crawling to his pack but drags his body and weapon to some bushes instead. A buddy tosses him some sterile gauze and Bleier wraps the leg—while his abandoned pack is perforated by gunfire.

From this position Bleier can’t see the machine gun’s location, but others call out and direct his aim as he lobs grenades—three dozen rounds—toward the source of the enemy fire. Then, out of ammunition, Bleier lies still, for almost two hours, and waits. It’s hot. He’s thirsty. He’s exhausted from the blood loss and from two days of fighting and two nights without sleep. He will not eat all day. He prays to God that he gets out of here alive.

In time—the enemy quiet—Bleier and others begin a long crawl to safety, through thickets, briars and mud. Across a road, there’s an open field. Twenty-two of them together now, including five wounded. But the NVA—130 of them—follow and about 2 p.m. the assault resumes.

It wasn’t the first grenade that trashed Bleier’s foot. Tommy Brown dived on top of Bleier when that one landed beside him, leaving Brown full of shrapnel and a two-foot hole in the earth. It was the second—the grenade that exploded at Bleier’s feet, that left his right leg quivering uncontrollably, his right foot maimed, his pants full of blood and his flesh riddled with shrapnel.

Bleier and the surrounded troops—nine of the original 32 dead, two missing in action and the rest seriously wounded—are in dire trouble. It doesn’t help that U.S. rocket support has started a fire, now steadily approaching the trapped soldiers braced for the enemy’s final assault.

Mysteriously, it never comes. And eventually, when a third platoon arrives to evacuate the wounded, to get them to a medevac helicopter poised two miles away, they move out. Bleier is carried on a poncho until it rips, is then slung over shoulders, then dragged—his legs banging over rocks and tree stumps as Bleier screams in pain—is then hoisted onto the back of an unknown soldier who carries him 500 yards to the waiting helicopter. It takes six hours to move two miles. It will be 14 hours after the initial gunshot wound before he gets any pain medications.

Airlifted to Tokyo, doctors remove 100 shards of shrapnel from his shredded foot and leg. Walking normally, maybe even without a limp, is the best-case prognosis.

Of course, the Rocky Bleier story doesn’t end here—although this would be a great story in itself. Football player serves his country, is awarded a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star; it’s a compelling war story, the story of an American hero. But it’s not even the best part.

The best part is what Bleier does after his tour of duty. He plays football again.

Rendered 40 percent disabled by the U.S. Army, Bleier lifts weights and runs sprints every day. He stretches with large rubber bands and runs stadium steps with 10-pound weights on his ankles. Less than a year after being medevac’d off the battlefield Bleier reports to the Steelers’ training camp—but is cut, put on waivers.

Art Rooney, the team’s owner, intercedes and has Bleier placed on injured reserve instead. Rooney, who had sent Bleier a note: “Rock, the team’s not doing well, we need you” when he first learned of Bleier’s injuries, pays the $20,000 salary so the war veteran can stick with his rehab. Rooney also pays for further surgeries (so his own team doctors, not the VA, can perform them).

Bleier returns again in 1971—and is again put on waivers. No team picks him up.

Bleier tries again in 1972. This time he hangs on as a special teams player. A year later, having taken two-tenths of a second off his best 40-yard-dash time and now bench pressing 440 pounds, he again plays on special teams…and thinks seriously about quitting. But teammates, inspired by his example, talk him into fighting back all the way.

In 1974, having carried the ball 10 times in his NFL career, he earns a spot in the starting backfield with Franco Harris. That two-back tandem, along with Terry Bradshaw, John Stallworth, Lynn Swann and the rock-ribbed Steel Curtain defense, would lead Pittsburgh to four Super Bowl championships. Bleier—with one foot shorter than the other, shoes of different sizes—would become an essential force in one of the NFL’s most celebrated dynasties, rushing for 4,000 yards in his 11 seasons (with Bleier and Harris each surpassing 1,000 yards in 1976).

But it was Bleier’s ability to get the tough few yards, to make the clutch catch, to throw the critical block—and his life of service and perseverance—that made him a fan favorite in blue-collar Pittsburgh, and across America. And a story of singular triumph against momentous tides.