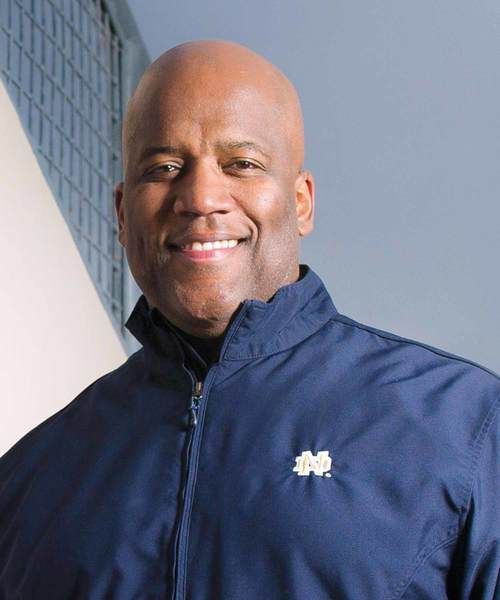

Rod West

The Man Who Saved New Orleans

Rod West knows exactly when the vast gulf between the power of a leadership position and the awesome responsibility it entails gaped open like a monstrous, devouring mouth.

West had just flown in a helicopter over the devastation left by Hurricane Katrina and now stood in Baton Rouge, La., before hundreds of electricity company employees to tell them their homes and former lives were gone. And as director of electric distribution operations for Entergy New Orleans, it was West’s job to restore the power to his hometown.

Heightening the tension of the moment, the former University of Notre Dame linebacker and tight end knew some of the employees would blame the messenger for barring their return home.

“I had a surreal feeling that I was an active observer of a movie in which I starred,” West says.

“I relied on what I learned at Notre Dame,” says West, now 44. “Trust, love and commitment. I had to answer those three questions Lou Holtz asked, but they had to answer ‘yes’ as well: Can I trust you? Do you care about me? Are you committed to working for excellence?

“Seven years later now, I see those employees and they remember vividly every word I said. They held on to the belief that I would do everything I could to make it OK.”

The slog of rebuilding began that day and would severely test the resiliency of the former member of the 1988 Irish championship football team. He got the job done, not only turning the lights back on, but later becoming the CEO to lead the company out of bankruptcy.

“You know that place you go when the monkey’s on your back,” he says, “when your legs are rubber, when it’s the fourth quarter or two-a-days—whatever cliché you have for when you want to quit—that’s the well I had to live in for months after Katrina.”

West credits his family, sports and Notre Dame with helping him locate that inner reservoir of strength.

West was born in Baton Rouge and raised in New Orleans. His father was a plant operator at Georgia Pacific and his mother was an administrator for Gulf States Utilities before working for Lockheed Martin. Neither went to college, but West says his family’s aspirations were never limited by what they lacked.

His parents expected a serious student—and that’s what they got. Attending Brother Martin High School, he realized early that he had athletic talent, too, though his first love was basketball. He played football, too, because he was big and fast and loved the camaraderie. He remembers great mentors like coach John Brown, who taught him to dig deep and shoot left-hand layups, but also Nancy Autin, who lifted the mystical veil draped over mathematics.

“I learned to have a passion for success, but football was not my life,” West says. He had decided to attend the U.S. Military Academy at West Point but agreed to let just-hired Coach Holtz visit him at home.

“Coach said I would get a world-class education and that I had a choice,” West says. “I could come to Notre Dame and become part of the turnaround of the country’s most-storied football program, or I could watch it on TV and regret it for the rest of my life.”

West decided to visit campus, showing up in loafers and a letter jacket in 12-degree weather. Holtz had done his homework; instead of flying West in for a weekend of partying, they brought him in on a Sunday and mainly talked about academics and future opportunity.

“Lou told the first recruiting class we were the worst in Notre Dame history, but we were like Peter,” West says. “He said we were the rock on which to build a return to prominence. And we were 24-1 in my last two years. Lou honored his promise.”

West’s true affinity for Holtz comes from actions off the field. Holtz encouraged West and teammate Pat Eilers to run for student body leadership. Even though some people objected because of their football fame, Holtz insisted they were a full part of the student body. They didn’t win, but West was encouraged to think big. When the team visited Washington, D.C., after the national championship, Holtz told the U.S. Senate that West would become either a senator or a CEO in Louisiana.

“Here it is 22 years since I graduated from Notre Dame, and I still wake up laughing that I had a dream [that] I was late for a Lou Holtz meeting,” West says. “You didn’t want to disappoint him. To disappoint him was to disappoint your teammates and your father.”

West carries those leadership lessons to his own life. His personal success on the field was hampered by injuries. He said he thought about the NFL but “was anxious to get on with it once I’d made up my mind.” He had studied for the LSAT on the plane to and from the Stanford game his senior year, and he used those scores to get into Tulane Law School.

He joined a New Orleans law firm in commercial litigation. He was also interested in sports law and represented some former teammates. He thought he was destined for a life in corporate and sports law, billing by the hour, but two events changed the course of his life.

The first was being elected in 1996 as the first black, and youngest-ever, president of the Notre Dame Alumni Association. He said getting an opportunity to reconnect with Notre Dame made him reflect on his future. He had met his wife, Madeline, when he was teaching at Tulane Law and was asked to recruit the former LSU basketball player to Tulane. When their daughter was two years old, West says, “I began to question if the path I was on—successful by all external accounts—was right. Was it bringing me satisfaction?”

In 1998, his father was killed in an electrocution accident while planting a tree. Entergy, a gas and electric utility and New Orleans’ only Fortune 500 company, called him about a job a year later. “Believe me, the irony of how I lost my father was not lost on me,” West says. “It was a sea change, and I took a pay cut, but it was about quality of life.”

In April 2005, West was completing his MBA at Tulane and was in charge of Entergy New Orleans electrical operations when the company ran a disaster scenario drill involving 20 feet of water covering the city. “My thoughts at the time were that this was a joke,” West says. “I was not an engineer, but I knew electricity and water didn’t mix. I remember asking what they expected me to do besides get my people out.”

When Katrina hit in August, West and other utility first responders evacuated their families in preparation. He holed up in the Hyatt Hotel, powered by a special generator, where he would live until Christmas. The first thing the company lit up was a bridge across the Mississippi River, not because it was easiest, but because the city needed a symbol of hope, something “to let folks know we’re working on it.”

By late September, power was rolling to much of the city. West clearly excelled in the crisis, considering that he was named president and CEO of Entergy New Orleans in 2007. He led the company out of bankruptcy—the storm took all their customers and income away—six months later. He also oversaw the replacement of 860 miles of damaged underground pipe, the largest natural gas pipeline rebuild in history.

“New Orleans no longer defines itself by Katrina, but by its aspirations today,” West says. “All the fury and devastation provided a clean slate to get it right. It’s been a wonderful narrative in human resiliency.”

In 2009, West was seriously considered for the position of executive director for the NFL Players Association. He decided to stay in his hometown, and Entergy promoted him to chief administrative officer and executive vice president of the holding company that owns the New Orleans utility and a much wider array of businesses, including 2.8 million utility customers in the South and a merchant nuclear company in the Northeast.

Success has given West even more opportunities to give back. He has been on the leadership boards of Louisiana State University, the New Orleans Convention Center, the New Orleans Business Council, and First Bank and Trust. He currently sits on the board of the Allstate Sugar Bowl and is also the point man for the New Orleans 2013 Super Bowl host committee.

West joined the Notre Dame Board of Trustees in 2009. He says that at 44, most of his goals are still in front of him: “I’ll continue to serve Our Lady’s University as long as she’ll have me.”

West’s daughter, Simone, is a high school senior. He hopes she will apply to Notre Dame, but he said his job is to support her no matter where she chooses. “Of course I want her to have all the things I didn’t,” West says. “But I also want her to desire to make a difference, not to define life by the money you make.”