Ryan Shay

Feting a Competitor

With his rippling deltoids and bulging biceps, Ryan Shay more closely resembled a lifeguard than the world-class distance runner he was. His jawline was an anvil, the likes of which you’d more commonly find in the pages of Marvel Comics. There was nothing wimpy about Shay’s physique, nothing soft in his approach to running.

“Ryan’s strength,” says his father, Joe Shay, “was his strength.”

Even his stare was hard. Shay was resolute and tenacious, a hammer both on the track and on the roads. Some middle- distance men possess an imposing finishing kick; Shay intimidated fellow harriers with an indomitable will (this is someone who quoted G. Gordon Liddy in his high school commencement speech).

“I’d walk into the locker room before practice,” says University of Notre Dame teammate Luke Watson, whose 3:57 mile-best was far superior to Shay’s 4:05, “and Ryan would greet me with, ‘Dude, Watson, I’m going to pound you today.’”

And he would.

“Ryan wore a brand of adidas flats called Adios, which, I mean, how apt was that?” says Watson, who would later room with Shay when both were upperclassmen.

“Nobody else could sustain that intensity on a day-to-day basis.”

Shay’s heart, like his other muscles, was outsized. It had been diagnosed as such early in his teen years and a later MRI, when he was in college, showed that it had since grown. At Notre Dame Shay would regularly wear a heart monitor to bed.

“Ryan’s resting heart rate was ridiculously low, even for a runner,” Watson says. “He woke up one morning and showed me the monitor. His heart rate had slowed overnight to 17 beats per minute.”

The average resting heart rate range for an athletic male in his early 20s is 49-55 beats per minute.

You may already know how Ryan Shay’s life ended.

On the morning of Nov. 3, 2007, at the U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials in New York, Shay was running near the front of the pack. At the 5.5-mile mark, he collapsed to the pavement with the suddenness of a lightning bolt. His heart, for reasons no one still fully understands, simply stopped. He never regained consciousness. At 8:46 a.m., just 81 minutes after the gun had gone off to start the marathon at Rockefeller Center, Shay was pronounced dead at Lenox Hill Hospital. He was 28 years old.

That was the end of Ryan Shay’s life. That was not the end of his story. To retrace that tale, we return to the stoplight-free town of Central Lake, Michigan, a four-and-a-half-hour drive due north of South Bend, just off the shores of Lake Michigan. That’s where Shay grew up with his seven brothers and sisters and his parents, Joe and Susan. Ryan, the fifth of eight, shared a bedroom with three brothers and a bed with one of them, Nathan, who would also later run for Notre Dame.

“We grew up pretty poor, to be honest,” says Stephan Shay, the youngest brother and an outstanding runner in his own right.

All of the Shay children ran, most excelled, and all were coached by either Joe or Susan at Central Lake High School. Even in a brood where four of the five brothers would run collegiately, Ryan’s talent and, even more so, his tenacity stood out.

“My whole life is basically schoolwork and running,” Shay told a local television reporter after a prep meet.

“And maybe some time for eating and sleeping in between.”

Shay also found time to work at a local restaurant. During the autumn of his junior year in high school he was hauling a few broken dishes to the dumpster when a shard filleted his calf open wide, a gash that required 70 stitches.

“Ryan just phoned us that he’d cut himself and came home,” recalls Stephan.

“We had to push the muscle back in before he even let us take him to the hospital.”

The accident would have ended any other runner’s cross country season.

“Ryan took the injury as an affront,” says Stephan.

“It was almost like, ‘(Screw) that, someone’s trying to hold me back.’”

Less than two weeks after the accident, Shay won the Michigan Class D cross country state meet, one of his four x-country state championships. No Michigan runner before or since has equaled that feat, and as an aside Shay was also his high school’s valedictorian with a 4.0 GPA.

Before Shay even matriculated at Notre Dame, he made an impression, according to future teammate Sean McManus.

“He stepped off the plane for his recruiting visit wearing racing flats,” says McManus, now the track coach at Fresno State.

“Ryan was all business. We took him out to run with the team and he pounded all of our upperclassmen.”

Like George Gipp, Shay hailed from a blue-collar, northern Michigan background and also like Gipp, he quickly established himself at Notre Dame as an athlete not to be harnessed. Before an early cross country meet in the fall of 1997, in his freshman year, Shay and his teammates were given the team’s strategy by coach Joe Piane: Stay together for the first three miles and then you may release. Shay ignored Piane’s direction, opening up a 30-yard gap between himself and the field in the first mile.

“I was standing along the course, on my recruiting trip,” recalls Watson, who is one year younger.

“Someone yelled, ‘Ryan, slow down!’ Ryan just flipped him off. He’d only been a Notre Dame student for three weeks. That left an indelible image.”

After the race, Piane asked Shay why he’d shot out to the front of the pack, solo.

Shay replied, “Coach, I did not come to Notre Dame to run slow.”

Shay may have been a nine-time All-American at Notre Dame and its only male NCAA track champion (in the 10,000 meters in 2001) of the past half century, but his success is not what burnished his legend. The uncompromising standards he set for himself are.

Two-time Olympian Molly Huddle (a 2006 Notre Dame graduate), the greatest distance runner, male or female, in school history, says that among Notre Dame harriers, “Ryan stories became Paul Bunyan stories.” The most repeated of those took place in the winter of 2002 after an indoor track meet in which Shay finished in second place to Alabama’s David Kimani (one year later, ominously, Kimani would collapse and die of a heart attack while eating lunch at his university’s dining hall).

On the day after the meet, a Sunday, Shay stepped out into a blizzard to do a 16-mile run. A couple hours later he returned to the off-campus apartment he shared with Watson and excitedly told him, “I got run over by a car.”

“Are you serious?” Watson asked.

Shay proudly pulled up a pant leg, exposing a calf tracked with tire marks and bearing a lump the size of a softball.

“Where did this happen?” Watson asked.

“Around the third mile,” Shay replied.

It took a moment for that to sink in.

“Wait, you got run over by a car and you kept going?”

That’s when Shay stared at Watson as if he were the lunatic.

Another blurb . . .

“My brother was atypical,” says Stephan Shay. And then some.

Determined. Stubborn. Combative. Frugal.

At Notre Dame Shay would tote around a book titled “How To Pay Zero Taxes,” which Watson, an accounting major, found comical. One year, living alone off campus, Shay got into a dispute with the electric company over his bill. He refused to pay it. They turned off the power. Defiant, he lived in darkness for weeks and as for television, he did not want one, anyway. The Kenyans did not watch TV.

Some athletes sign their names, others add a smiley face. When Ryan Shay signed an autograph, he’d write “Maximize your potential.”

“With Ryan it wasn’t a catchy platitude,” says Huddle, “it was his mantra.”

Maximize your potential.

“Ryan couldn’t stand people who wouldn’t work hard,” says his father.

“When Ryan first arrived at Notre Dame, he didn’t understand why people there didn’t work harder.”

Shay was the runner who, on frigid days when Piane told the team they could run indoors at the Joyce Athletic and Convocation Center, would proudly return from an arctic slog with icicles in his beard.

When a younger Irish runner, Kurt Benninger (Huddle’s future husband), broke Shay’s school 5-K mark, Shay was annoyed. He took Benninger out for what he said would be an easy 20-mile distance run.

“Ryan is setting a blistering pace, 5:10s, doing everything he could to drop Kurt,” Huddle recalls with a chuckle.

“But Kurt hung with him. After that Ryan said, ‘OK, I like Kurt.’”

In their last autumn together running cross country for the Fighting Irish, Watson outkicked Shay in the last strides to win the Notre Dame Invitational. Afterward, Shay seethed.

“How can I expect to be the best in the country,” he asked aloud, “if I can’t even beat someone on my own team?”

Most teammates would take offense. Watson did not.

“I knew where Ryan was coming from,” he says.

“Neither Ryan nor I were ever content with other people’s standards.”

Shay’s only solution for his failure was to amp up the workload.

During the team’s subsequent fall break trip to Michigan, he subjected himself to suicidal three-a-day workouts.

“He must have put in 150 miles that week,” says Watson.

“What Ryan was doing was unheard of.”

But if Shay was monomaniacal about running, he was not a megalomaniac. Five weeks after Watson had outkicked him, the two found themselves running in the NCAA Cross Country Championships in Furman, South Carolina. Watson was in 12th place with a mile or so left and was beginning to feel himself fade from the pack. Suddenly he felt a tap on his shoulder. “Let’s go, Watson.”

With that the two Domers spent the final mile of their last race together picking off other runners.

“We just rolled past guys,” says Watson, who would finish sixth, one place behind Shay.

Less than two weeks before the 2007 Olympic Trials, Shay and his bride of four months, Alicia, returned to South Bend for some final training runs at sea level. Alicia had been a two-time NCAA champion in the 10,000 (the race in which Shay had won his men’s title) and was also an Olympic hopeful. The two were making their home in Flagstaff, Arizona, at 7,000-feet altitude to maximize their potential.

“Ryan was such a perfectionist, but I found it charming,” says Alicia Shay, who grew up on a ranch in Wyoming.

“The night after we met he did all this research on Wyoming and rodeos and was trying to discuss it with me. He didn’t even own a pair of cowboy boots yet.”

The couple had met in 2005 at the New York City Marathon. On the night of the race — Shay, slightly injured, had finished 18th with a time of 2:17:14, nearly three minutes off his personal-best — they had been part of a group of elite athletes that went out to celebrate. Now, two years later, they would be returning to the city where they had met.

“Ryan and I went on some runs together that final week in South Bend,” says Watson, who at the time was in graduate school and working as an assistant coach under Piane.

“The three of us had dinner together a few times. I remember, on their last night in South Bend, we watched the movie ‘We Are Marshall.’”

Watson’s voice drifts off.

News of Shay’s collapse reached those in his orbit in different ways.

McManus was watching the trials on television and heard that his friend had fallen.

“What’s going on?” he texted former teammates.

“Not good,” was the reply.

Huddle, who was watching inside Central Park, noticed that Shay had not made it to the seven-mile mark where she was standing. Both she and Shay by this time were professional runners, both sponsored by Saucony. A Saucony rep standing beside her broke the news to her.

“I was just numb,” says Huddle.

Alicia Shay had seen her husband pass her less than a mile north of where he would eventually fall. A friend texted her to head to Lenox Hill.

“I just remember running out of the park and asking strangers, ‘Where is Lenox Hill?’” she says.

When she arrived, it was too late. Alicia Shay would sit alone in a hospital room, devastated, holding her deceased husband’s hand for an hour or so.

In Brooklyn, Michigan, site of the state high school cross country meet, Roger Send and his daughter, Amanda, who was competing, could not quite believe the news. They knew Joe Shay well, had expected to see him and his Central Lake squad at the meet. But now Joe and Susan had taken a detour to the airport.

“We were shaken, we just couldn’t believe it,” says Roger. “But we knew that we had to do something.”

In the ensuing days after Shay’s death, Joe and Susan held nightly runs at the Central Lake track. The idea was for friends, family, fans and admirers to run a lap or two in Shay’s honor. A moving wake on a quarter-mile oval. The inside lane, lined with luminary candles, would remain empty. That would be Ryan’s lane.

On Thursday of that week Roger and Amanda Send arrived at the track a few hours before the other mourners. The father and daughter had conceived a unique idea: to run, on the track, the final 20.7 miles that Shay had not been able to complete. They would do 83 laps around the track on a cold, rainy November afternoon and evening.

“We knew that we wanted to do something,” says Roger Send.

“When we arrived there was still football practice going on. We just started running.”

Gradually, hundreds of runners showed up. Word filtered out to Joe and Susan Shay about the Sends’ tribute to their son.

“Before the final lap, Joe and Susan stopped us,” says Send. “They handed each of us a candle and asked us to run on the inside lane. Ryan’s lane.”

Like Roger Send and his daughter, Matt Peterson wanted to do something to help sustain Shay’s legacy. So he and a few friends, who already staged a 5- and 10-K in Charlevoix, Michigan, on the last weekend of July, have added a Ryan Shay Mile. The event, which features elite runners, has seen nine sub-four minute miles in the past five years.

“We run it right down Bridge Street and in the last quarter-mile the street is lined with 10,000 spectators,” says Peterson.

“Elite runners tell us it’s their favorite atmosphere for a race.”

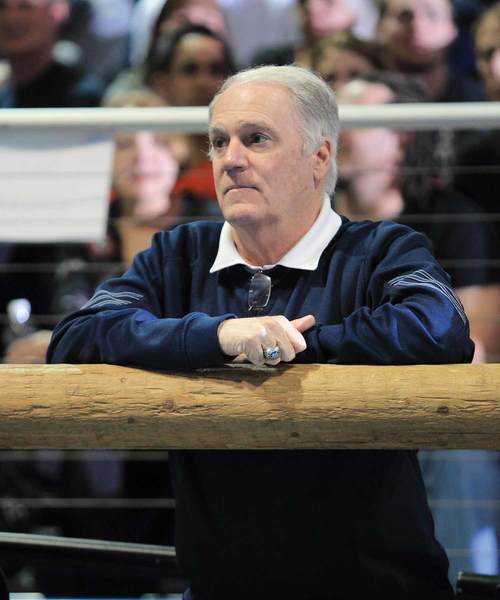

Joe and Susan Shay, who appear at Peterson’s race each July and meet the runners, have created a scholarship in Ryan’s name at Central Lake High. They also stage their own annual “Ryan Shay Midsummer Night Run” in their hometown, a 5- and 10-K that draws hundreds.

Everyone whose life was touched by Shay, in some way, commemorates him each Nov. 3.

Luke Watson, now a professor of accounting at the University of Florida, runs 5.5 miles each year on the date.

In 2008, nearly one year to the day Shay passed away, McManus and more than a dozen former teammates of Shay’s, plus members of Alicia’s family, ran the New York City Marathon.

“Ryan was such a character,” McManus says fondly. “We wanted to be together for him. Whenever we get together, it’s not long before Ryan stories come out.”

This past year McManus’ wife was out of town so he did the run with their two preschool children in a stroller.

Alicia, now remarried and living in Flagstaff, retreats to the pines alone for a long walk and a run.

“Friends used to want to be with me on that day,” she says.

“A couple of years ago a few of us drove up to the Grand Canyon, but I had a complete meltdown. My husband (Chris Vargo) has been so understanding and helpful, but that is a day when I just need to be by myself.”

Stephan Shay, who now lives in Ventura County, California, endeavors to uphold his brother’s memory by adhering to his principles, not just on Nov. 3, but every day.

“I’ll go out for a run and I won’t put any conditions on myself how far I go,” says Stephan.

“I still have the last pair of shoes Ryan sent me. I even kept the box he sent it in. Having it makes me feel better.”

When Stephan turned 28 years old, he ran the New York City Marathon.

Not far from the spot where Ryan fell, there is a park bench with Ryan’s name on it. An inscription reads, “It is necessary to dig deep within oneself to discover the hidden grain of steel called will.”

“When I passed that spot, it was very emotional for me,” says Stephan.

“I teared up. I’ve never teared up in any other race. It’s difficult to share these stories, but the more I do, the more I remember him.

“That’s the bright side. The worry is that I’m going to forget my brother.”

He won’t.

No one will.

Not Ryan Shay.