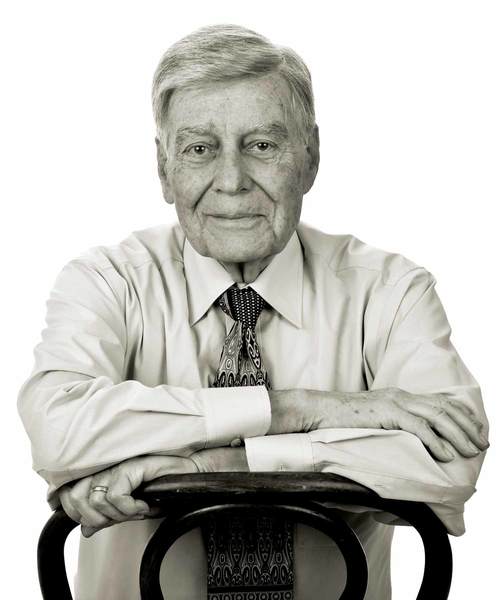

Steve Boda

The ultimate Notre Dame football historian

A humble, split-level home on a quiet street in suburban Kansas City seems an unlikely site for a treasure chest of Notre Dame football history.

But if you are looking for details of any Fighting Irish game since their debut in 1887, a small office on the second level of Steve Boda’s house has more information than anywhere west of, east of or maybe even in South Bend.

Boda spent 40 years with the NCAA statistics bureau and its predecessor—the National Collegiate Athletic Bureau (NCAB)—before retiring in 1989. Juanita, his wife of 50 years, passed away almost a decade ago, but Boda remains in his Shawnee, Kan., home with his favorite companion, a butterscotch-colored cat named Duffy.

Now 86, Boda has authored and contributed to numerous books and records publications, including three editions of the Ronald Encyclopedia of Football. He compiled the first NCAA Football Record Book in conjunction with the sport’s centennial celebration in 1969, and updated it annually for the next 20 years. More than a statistician, Boda is a historian, responsible for much of the information about the early days of the game. In three editions of the NCAA’s Football’s Finest, he helped recognize college football’s early stars, whose feats pre-dated the standardization of statistics.

“Before 1937 there were no national guidelines for football statistics,” recalls Boda. “It was then that Homer Cooke devised a system of statistics, which was officially adopted by the Football Rules Committee in 1940.”

Despite his unassuming demeanor, Boda’s work has not gone unrecognized. He has received two awards from the College Sports Information Directors of America (CoSIDA), one in 1983 for Meritorious Service and another in 1990—the prestigious Arch Ward Award presented annually for outstanding contributions to the field of college sports information.

In 1965 he was honored by Notre Dame with a plaque saluting “his many years of untiring, unselfish, painstaking and dedicated research and compilation of the countless number of Notre Dame football records. His contributions to Notre Dame football … must be considered the most earnest and significant historical documentation of any collegiate football team in the land.”

Even in retirement, he continues his research of college football, particularly related to Notre Dame, as he meticulously recreates play charts and statistical sheets from games long ago. His office is lined with cabinets that overflow with hanging files, each one with news accounts and data for a specific Notre Dame game, starting with its inaugural contest—an 8-0 loss to Michigan in 1887. Because of his work, the University has two sets of football statistics—one from 1917 through 1936 and the other from 1937 through the present day.

Why 1917?

“It represents the first year in which at least one play-by-play account is available for every game, and coincidentally it is George Gipp’s first season. He holds or shares 78 game, season and career statistical highs for the 1917-36 period.”

Because of Boda’s research, players of that era are still recognized for their accomplishments, even though the numbers may be dwarfed by the high-octane offenses of the modern game.

According to John Heisler, senior associate athletics director for broadcast and media relations, Boda “may have more historical records about Notre Dame football than we do.”

Heisler tells the story of former sports information director Roger Valdiserri printing Boda’s home phone number backwards on the first page of the media guides from 1976 through 1979.

“It looked like some random number,” says Heisler. “But we wanted to have it handy in case we had to call him in the middle of a game to ask a question.”

And sometimes they did, although Boda modestly says it “was only once or twice a year.”

Any college football fan would find Boda an engaging conversationalist, with a memory that bridges the decades. His quiet dedication has enhanced the knowledge and enjoyment of the game for generations of fans. His work has allowed comparisons of teams and players from different eras. Without him, it is fair to say that many sportswriters would be left with unfinished stories, and bar patrons with unsettled arguments.

But it is his affinity for the Irish that makes Boda’s story so interesting. He sums it up in one short, powerful sentence.

“Notre Dame saved my life.”

A strong statement, but his personal history supports its authenticity. Boda is a consummate member of America’s “Greatest Generation,” and his life could serve as inspiration for a Charles Dickens novel in a 20th century setting.

Born in 1924 in South Bend’s St. Joseph Hospital (where Gipp died four years earlier), Boda was the oldest of five children. His father, of Austrian-Hungarian descent, cared little for American football.

At age 6, Boda grew interested in the game from hearing his friends talk about Notre Dame and coach Knute Rockne, and he pestered his father to take him to a game.

“I had never seen a game before that day. It was the opener of the new stadium—Oct. 4, 1930, and Notre Dame beat SMU, 20-14.”

For whatever reason, Boda took a pad of paper along and began charting plays. The exercise came naturally, and he had set himself on a path that would determine a career. His father took him to more games, and he would follow others on the radio—all the time charting statistics. His favorite player was Nick Lukats, a halfback in the early 1930s, who later served as a technical advisor for the film Knute Rockne: All-American.

In 1933 tragedy struck the family when his mother died of complications from a goiter. Unable to care for five young children and financially support the family during the Depression, Boda’s father took them to the Indiana Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Children’s Home in Knightstown, about 40 miles east of Indianapolis. Though their father occasionally would visit, the children became wards of the state.

“There were about 600 kids in the orphanage, a state institution,” remembers Boda, who was 9 when he entered. “My siblings and I were separated into different buildings according to our age group. We didn’t get to see each other a lot.”

Boda says they were well fed, clothed and educated in the orphanage, but it was “a sad place.”

It was here that Notre Dame football sustained him. On Saturdays in the fall, when other residents were playing outside, Boda listened to the Irish games on an Indianapolis radio station and kept the statistics.

“The only thing that I could hold on to from South Bend was Notre Dame. There was only one radio in the building, and every now and then the resident bully wanted to hear the hit songs and made me change the channel. But I still managed to follow the games. I learned much later that bully became a millionaire insurance executive.”

By age 12, Boda convinced the high school coach to let him keep stats. A few years later, while working at a South Bend high school game, he attracted the attention of a tall visitor to the press box.

“He told me he had never seen anyone chart a game like I did. It turned out to be Joe Petritz, sports information director at Notre Dame. He asked me to join his statistics crew for its next game against USC.”

Unable to find a job after graduation, Boda in 1942 entered night school, where he learned the tool and die trade and then went to work at Bendix Aviation. Living again with his father, he worked all the overtime he could, and with their combined incomes they were able to demonstrate their ability to support the other four children and have them released from the Children’s Home.

He served in Europe during World War II as a member of the infantry, and then returned to attend college at Indiana University under the G.I. Bill. He graduated in 1949 with a degree in English literature, and with a recommendation from Petritz he was hired by Cooke in the NCAB’s New York office. At that time the Official Football Guide had only one page of records, a far cry from the comprehensive guides Boda later compiled. The NCAB was partially supported by the NCAA, which took full control of the bureau in 1959 and moved it, along with Boda, to the Kansas City area in 1975.

Boda’s trove includes more than 150 films of Irish games, some from the 1930s and ’40s. He has at least one newspaper account, and in some cases as many as 10, for every Notre Dame game played from 1887 through 1995, and has since used the Internet to assemble information. Among the most intriguing of his collectibles is a game program, dated Nov. 23, 1963, featuring Notre Dame at Iowa.

“President Kennedy was assassinated the previous day. The game was cancelled and never played.”

Boda is unpretentious and reserved, but he takes understandable pride in his career and what Notre Dame has meant to him.

“After what I went through growing up, I have had such a good life. I got to do exactly what I wanted to do. Notre Dame was the reason why.”

Boda has made plans in his will to bequeath his copious files to Notre Dame.

“From whence it came,” he says, “although they might have to pay for a U-Haul.”