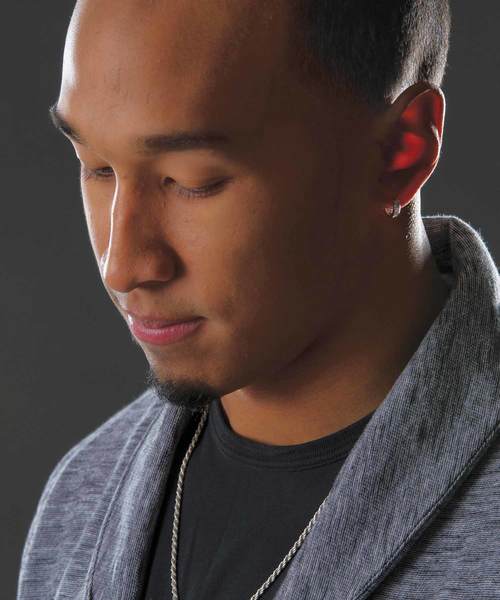

TJ Jones

Making his father proud

The first phone call from Georgia came to Reggie Brooks, who then went to find Tony Alford.

Brooks is a University of Notre Dame Monogram Club executive (and 1992 All-America running back at Notre Dame). Alford is an assistant coach on the staff of Irish head football coach Brian Kelly.

It was mid-day on June 21, 2011, and the world of Notre Dame wide receiver TJ Jones, then 19, was about to be shattered.

Alford knew where Jones was. He was in the Loftus Sports Center on the east edge of campus, working out with teammates. Alford walked into the building.

“We’re not allowed (at summer workouts) so most everyone knew something’s not right,” Alford said.

As TJ remembered it, “He grabbed me and said, ‘I’ve got to talk to you.’ I thought he was mad at me about something.”

What TJ was about to learn was that his father Andre, 42, had collapsed back home in Roswell, a suburb of Atlanta. Alford got TJ on a phone with his mother Michele, who said, as TJ recalled, “You have to come home now.” What TJ did not know then was that Andre had suffered a brain aneurysm that he would not survive.

Brooks said of that day, “It’s one of those deals where you get the news and it hits you hard. How do you relay that to a 19-year-old kid? I knew how much Andre had invested in TJ and how close they were. (Brooks enrolled at Notre Dame the fall after Andre and his teammates won the 1988 national title.) You just can’t fathom this happening.”

The University arranged to fly Alford, TJ’s girlfriend and TJ on a private jet to a small airport outside Atlanta. Upon arrival, Alford determined that TJ needed private time with his family. He put him in a cab by himself.

When he arrived in the lobby of North Fulton Hospital in Roswell, TJ, still in the dark on details, realized when he saw so many friends and neighbors crowded in the lobby that the news could not be good.

Later, he saw his father, attached to an array of tubes, and realized that there was almost no hope. One final test, his mom told him, was scheduled for the next morning to see if there was any chance. TJ sent his five siblings home and stayed up all night with Michele.

“I felt I was the man of the house now,” something Andre would say to TJ, even at age 6 or 7, when he left home.

Brooks, who had known TJ since he was a toddler, said, “I’ve never seen a young man hold it together that well. He’s always had to be the glue for his family.” More than two years later, Brooks and Alford both get emotional talking about that time.

Andre—an Irish football letter-winner in 1987-88-89-90 and outside linebacker starter in 1989 and ’90—died the following day, having never regained consciousness. He left behind Michele, TJ and six other children, ranging in age from 9 to 23. TJ now felt he was responsible for his family’s future.

“I never really felt I had time to be down, to feel bad. I never really talked to anyone about it. There were a lot of things I held in, but I felt it was the better thing to pursue my degree, to pursue a career in the NFL and to support my family.”

Despite his expressed stoicism, both TJ and Alford concede how difficult the next months were.

“My sophomore year in football, it was hard to concentrate,” recalled TJ. Alford said, “You could see the strain. You could be with him in a meeting, and you could tell he wasn’t really there.” Still, Jones started every game but one and had 38 receptions for 366 yards.

Tribute was paid to Andre at the 2011 season’s first game versus South Florida. Michele, who TJ says will still not talk about Andre’s death, was very emotional as she made her first visit to Notre Dame Stadium that day. Between her responsibilities with the remaining three youngest children at home and the expense, it was seldom realistic for her to come to Notre Dame and watch TJ play.

Karen Heisler, who teaches in the Notre Dame department of film, television and theatre (TJ’s major), remembers Jones from that first semester of sophomore year.

“I think when I had him that semester you could tell he was a little shell-shocked. He didn’t say much in class. Didn’t smile much. As the semester wore on, he came out of his shell a little bit.”

Alford said, “The growth process from then to now is just unbelievable. He’s a man.”

Though most who know TJ talk about his being quiet and introspective, he is not shy. One Notre Dame official who interacted with him by happenstance was surprised a few days later when TJ, despite his ambitions for a professional football career, wanted to drop by the office to learn more about the how Notre Dame is run.

Brooks says of TJ, “He’s not easy to read. I give him some space. He’s always been pretty quiet. But you just point him in the right direction and he’s going to go get it. Once he figures it out, he’s locked in.”

Jones, a nondenominational Protestant, concedes that the loss of his young father so unexpectedly was a challenge to his faith.

“I’m still trying to figure out what my relationship to God is,” he says. And he continues to bear most of his burdens silently. As much as he appreciates what his coaches, his dad’s former teammates (Raghib “Rocket” Ismail is his godfather) and others at Notre Dame have done for him, he said, “I didn’t want to feel like I needed people to lean on. I’ve never been that kind of person.”

Alford says that while TJ is relatively quiet “he sees everything.” A pivotal example of this trait might be the visit that TJ and the Jones family made to SeaWorld when TJ was 10 years old. Something he witnessed there clicked, and ever since he has been interested in performing at SeaWorld. Although he had also considered what might be a more conventional career route of sports broadcasting, he remains fixated on working in an aquarium.

In the summer of 2013, he took some time away from campus to work with sharks at The Florida Aquarium in Tampa. Knowing the reach of the Notre Dame network, Jones worked through Brooks who was able to arrange the visit to Tampa.

“Being inside the tank,” he told und.com soon after, “you get to see the aquarium from a very different perspective. You get to see up close and in real life the way that sharks, fish, eels and turtles all interact with one another. You get to see that sharks aren’t really as ferocious and violent as everyone thinks. You leave them alone and they’ll leave you alone.”

He says working as a performer in the Shamu show with killer whales at SeaWorld remains his dream job, “I used to think I couldn’t do it because I’d need a marine biology degree, but it’s more of a performance job.” He added that his public speaking training through film, television and theatre would help. “And psychology helps, because animals are just like people.”

His love of SeaWorld is perhaps consistent with what many of his friends say is his way with little children. Alford recalls how upset his youngest son, 8-year-old Brandon, was when he heard the coach giving TJ a hard time during a visit to the Alford home. Brandon said, “Don’t do that to TJ. He’s my best friend.” Alford said that for a long time Brandon didn’t even know TJ was a football player.

TJ is, of course, a football player. He is set to graduate in December 2013 and begin soon after preparing for the 2014 NFL Draft. The recognition that ballooned last year has only intensified as he climbs the list of all-time productive Notre Dame receivers. Thinking back to the pain of his sophomore year, he said the greater attention to his accomplishments has helped in his recovery,“…knowing that your hard work is paying off.”

And whenever he discusses the NFL, the next thing he mentions is being able to help his mom Michele back in Georgia. The young man who doesn’t feel a great need to rely on others looks to be relied upon.

Whether it’s Shamu or playing football on Sundays, Heisler said, “I have no worries that TJ will be a success. Whatever he decides to do, he’ll be fine.”