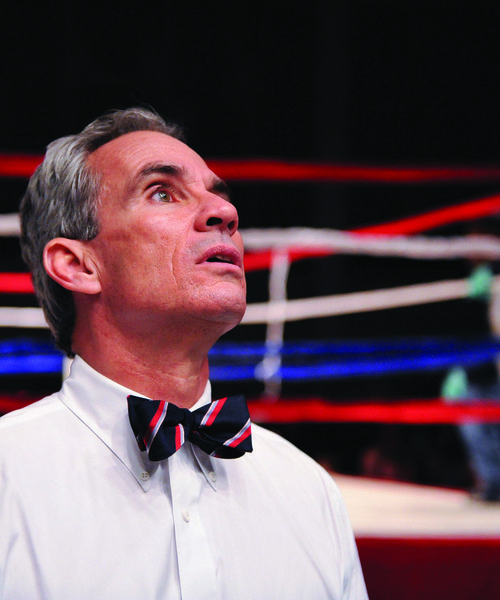

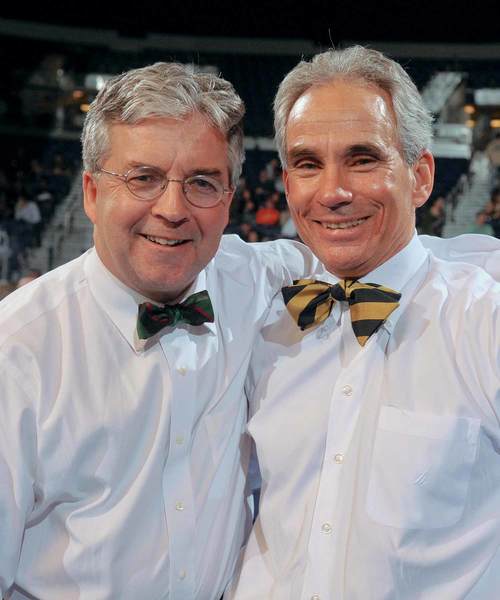

Tom Suddes & Terry Johnson

Championing the Bengal Bouts is their life

To the uninitiated, a punch is an act of violence.

Motivated by anger, perhaps thrown by the wrong person in the wrong place at the wrong time, a punch can destroy a body, a relationship, even a life. But that same powerful blow—delivered by men with strong hearts, strong minds and pure souls—can build rather than destroy.

Knute Rockne started the University of Notre Dame’s boxing program in the 1920s, and it became known as the Bengal Bouts in 1930. Over more than 80 years, millions of punches have been thrown by Notre Dame boxers. The punches are awkward and halting at first, but soon become strong and sure.

A single thundering uppercut finds its mark, and a brick is laid. It may be a brick in a modest bungalow of skill for the boxer who threw the punch; it may be a brick in a mansion of resiliency for the one who received it. Perhaps, it is both.

Indeed, to watch the Notre Dame boxers march into the arena and step into the ring, having already thrown and absorbed thousands of punches, it is to see not the beaten, decimated by the blows. Instead, it is to see the strong, standing erect, confident, determined.

This is the result when men—and women, since the 1990s—understand how to build with punches.

Rockne entrusted the program to Dominic “Nappy” Napolitano, a Notre Dame graduate and physical education professor. Napolitano knew how to build with punches, leading the program for over 50 years until his death in 1986.

Napolitano also knew that if all he did was teach his men how to conquer their opponents in the boxing ring, that if their focus was only to build themselves up, they’d run the risk of never becoming anything more than monuments to themselves. While sturdy and handsome on the outside, they’d be empty and soulless on the inside.

So Napolitano made sure that the Bengal Bouts were about more than men getting into the best shape of their lives, about more than learning how to snap a jab or slip a punch. At his insistence, all proceeds from the Bouts were devoted to the missionary work of the Congregation of the Holy Cross in what is now Bangladesh. Napolitano’s simple credo became the guiding vision for the program, one that endures to this day: “Strong bodies fight, that weak bodies may be nourished.”

With a population of more than 150 million people contained within a country the size of Wisconsin, the people of Bangladesh have lived in overwhelming poverty for centuries, prompting Pope Pius IX to invite the Congregation of the Holy Cross to what was then the Indian province of East Bengal in 1853.

As Napolitano pushed Notre Dame’s boxers to push themselves to complete one more set of pushups, come out of their corner for one more round, launch one more punch, their sacrifice was paying off not just in building strong bodies, but also in building lives halfway around the globe.

Terry Johnson had never set foot inside a boxing ring when he arrived at Notre Dame in 1970. Johnson didn’t show up to help feed starving children; he simply figured boxing was as good a way as any to stay in shape.

Each year, Napolitano would share letters from Holy Cross missionaries, describing the abject poverty of the region and the hope provided by the funds raised by the Notre Dame boxers. The boxers learned of the bricks their predecessors had laid—medical facilities, schools and a college—all constructed with proceeds from the Bengal Bouts. Before long, the boxers were not only training for themselves, fighting for themselves, but they were also fighting for people they had never met.

“It’s like osmosis,” says Johnson.

“It was just understood and passed along from the older guys. You walk in the boxing room and you see the photos on the wall. It’s like there are 1,000 guys looking over your shoulder.”

Napolitano’s men learned to reach deep inside themselves in search of more than they ever knew they had. And what they found, they shared.

By 1970, Tom Suddes had his sights set on his third Bengal Bouts championship and his fourth trip to the finals. But, just as much, he had set his sights on helping rookies like Johnson. As one of the Bengal Bouts captains, Suddes helped lead training, tutor boxers and handle all of the behind-the-scenes demands.

And he hasn’t stopped for 44 years.

Since graduating from Notre Dame, Suddes has served as a tactical officer in the United States Army, led a Notre Dame capital campaign that raised a then-unprecedented total of $180 million and founded the Suddes Group, which has helped organizations worldwide raise over $1 billion.

The one constant throughout has been Suddes’ commitment to the Bouts. Each year since leaving Notre Dame and moving to Columbus, Ohio, Suddes has returned to campus for six weeks to train and coach Notre Dame boxers and to officiate bouts.

“Coach Suddes is one of the craziest guys I have ever met,” says 2003–04 Bengal Bouts captain Pat Dillon.

“Voluntarily, he basically sets aside his own personal and professional life for six weeks every year to coach boxing in the middle of winter in South Bend, Ind., for no money.

“He has taught thousands of guys over the years not just how to box, but also how to commit to something bigger than yourself.”

Johnson served as an assistant coach while earning his degree from the Notre Dame Law School in 1978, and has returned to officiate bouts each year. But Johnson’s contributions go far beyond his time in the ring. Along with tackling a variety of other essential tasks, Johnson has taken responsibility for making sure that the safety of Notre Dame’s boxers is uncompromised.

In building a law practice that has pioneered the representation of workers stricken with asbestos-related disease, Johnson has developed considerable respect for the great value of diagnostic medical tests and the importance of measures designed to prevent significant injury and illness.

“The number-one priority for us is making sure the boxers are safe,” says Johnson.

“Our safety protocol is the most comprehensive of any boxing program in the nation.”

Like so many other Bengals boxers, Suddes and Johnson were overwhelmed by the stature of Napolitano and the tradition of the Bengal Bouts as novices. Today, as keepers of the tradition, both have a difficult time with the realization that they have been stewarding the program for nearly as long as Napolitano did.

“He was such a humble man,” Johnson says.

“He used to say, ‘If I have found any humility in life, it was from my boys.’”

Apparently, humility is just one more thing Napolitano built into his protégés.

“Terry has one of the biggest hearts I’ve ever encountered,” says Chris Cugliari, a 2010 Notre Dame graduate who served as president of the Bengal Bouts his senior year.

“He prides himself on maintaining the tradition of the program, which is a group of young men and women who will push themselves for a cause greater than themselves.

“He helps ensure that the Bengals Bouts aren’t about anybody taking advantage of the missions or making money off of the sacrifices of young men and women, but are rather about self-discovery through both the missions and the sport of boxing.”

Indeed, the values of the Bengal Bouts are as unchanging as those photos on the walls of the boxing room. In an era of ubiquitous commercialization, the Bengal Bouts remain sponsor-free and not for want of opportunity. Proceeds are generated by gate receipts and by advertisements sold by boxers for the tournament program. In 2010, the Bengal Bouts raised more than $100,000 for the first time, pushing the grand total of support provided to the Holy Cross missions to over $1 million.

“The day the Bengal Bouts add a commercial sponsor is the day I retire,” says Johnson with a laugh.

“Nappy used to say that boxing was the purest form of competition, and not much has changed in 80 years.”

One thing that has changed is the connection between the Notre Dame boxers and their beneficiaries in Bangladesh. For many years, Suddes was the only Bengals boxer ever to visit Bangladesh, where he made a one-day stop after winning a trip around the world. But in 2008, five boxers traveled to Bangladesh, at long last meeting the people they had been helping, seeing the buildings they had helped build.

That initial visit—the first of several treks—was chronicled in the award-winning film Strong Bodies Fight: The Story of One Boxing Team’s Fight Against Poverty. Produced by 2008 Bengal Bouts captain Mark Weber and Notre Dame film professor William Donaruma, the film brings to life the Holy Cross missions and the people they serve.

“Nappy used to stand up there and talk about how far one dollar would go,” says Johnson.

“Mark was able to go over there and make it that much more real for everybody.”

One of the most compelling aspects of the film is how the citizens carry themselves. Against stifling poverty and a daily existence that often seems physically and psychologically overwhelming, the Bangladeshi are unfailingly upbeat and proud.

If you look closely enough, you can recognize in them the handiwork of Napolitano, Suddes, Johnson and so many others who have been built up, one punch at a time, one brick at a time.